Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Valerie Thomas, Professor of Industrial Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology

Countries around the world have been discussing the need to rein in climate change for three decades, yet global greenhouse gas emissions – and global temperatures with them – keep rising.

When it seems like we’re getting nowhere, it’s useful to step back and examine the progress that has been made.

Let’s take a look at the United States, historically the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter. Over those three decades, the U.S. population soared by 28% and the economy, as measured by gross domestic product adjusted for inflation, more than doubled.

Yet U.S. emissions from many of the activities that produce greenhouse gases – transportation, industry, agriculture, heating and cooling of buildings – have remained about the same over the past 30 years. Transportation is a bit up; industry a bit down. And electricity, once the nation’s largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, has seen its emissions drop significantly.

Overall, the U.S. is still among the countries with the highest per capita emissions, so there’s room for improvement, and its emissions haven’t fallen enough to put the country on track to meet its pledges under the 10-year-old Paris climate agreement. But U.S. emissions are down about 15% over the past 10 years.

Here’s how that happened:

US electricity emissions have fallen

U.S. electricity use has been rising lately with the shift toward more electrification of cars and heating and cooling and expansion of data centers, yet greenhouse gas emissions from electricity are down by almost 30% since 1995.

One of the main reasons for this big drop is that Americans are using less coal and more natural gas to make electricity.

Both coal and natural gas are fossil fuels. Both release carbon dioxide to the atmosphere when they are burned to make electricity, and that carbon dioxide traps heat, raising global temperatures. But power plants can make electricity more efficiently using natural gas compared with coal, so it produces less emissions per unit of power.

Why did the U.S. start using more natural gas?

Research and technological innovation in fracking and horizontal drilling have allowed companies to extract more oil and gas at lower cost, making it cheaper to produce electricity from natural gas rather than coal.

As a result, utilities have built more natural gas power plants – especially super-efficient combined cycle gas power plants, which produce power from gas turbines and also capture waste heat from those turbines to generate more power. More coal plants have been shutting down or running less.

Because natural gas is a more efficient fuel than coal, it has been a win for climate in comparison, even though it’s a fossil fuel. The U.S. has reduced emissions from electricity as a result.

Significant improvements in energy efficiency, from appliances to lighting, have also played a role. Even though tech gadgets seem to be recharging everywhere all the time today, household electricity use, per person, plateaued over the first two decades of the 2000s after rising continuously since the 1940s.

Costs for renewable electricity, batteries fall

U.S. renewable electricity generation, including wind, solar and hydro power, has nearly tripled since 1995, helping to further reduce emissions from electricity generation.

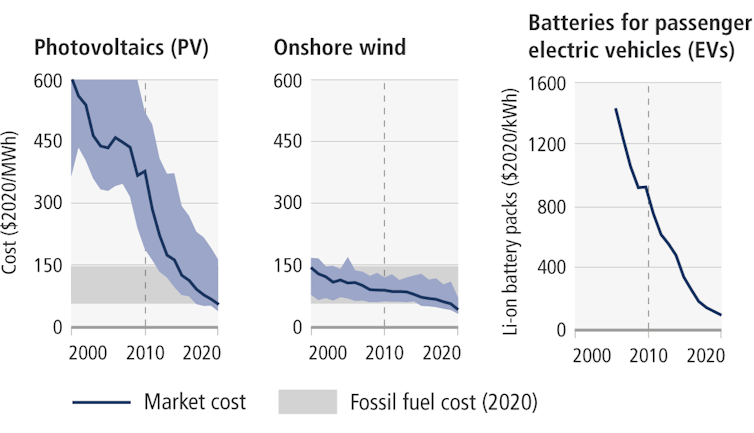

Costs for solar and wind power have fallen so much that they are now cheaper than coal and competitive with natural gas. Fourteen states, including most of the Great Plains, now get at least 30% of their power from solar, wind and battery storage.

While wind power has been cost competitive with fossil fuels for at least 20 years, solar photovoltaic power has only been competitive with fossil fuels for about 10 years. So expect deployment of solar PV to continue to increase, both in the U.S. and internationally, even as U.S. federal subsidies disappear.

Both wind and solar provide intermittent power: The sun does not always shine, and the wind does not always blow. There are a number of ways utilities are dealing with this. One way is to use demand management, offering lower prices for power during off-peak periods or discounts for companies that can cut their power use during high demand. Virtual power plants aggregate several kinds of distributed energy resources – solar panels on homes, batteries and even smart thermostats – to manage power supply and demand. The U.S. had an estimated 37.5 gigawatts of virtual power plants in 2024, equivalent to about 37.5 nuclear power reactors.

IPCC 6th Assessment Report

Another energy management method is battery storage, which is just now beginning to take off. Battery costs have come down enough in the past few years to make utility-scale battery storage cost-effective.

What about driving?

In the U.S., gasoline consumption has remained roughly constant and electric vehicle sales have been slow. Some of this could be due to the success of fracking: U.S. petroleum production has increased, and gasoline and diesel prices have remained relatively low.

People in other countries are switching to electric vehicles more rapidly than in the U.S. as the cost of EVs has fallen. Chinese consumers can buy an entry-level EV for under US$10,000 in China with the help of government subsidies, and the country leads the world in EV sales.

In 2024, people in the U.S. bought 1.6 million EVs, and global sales reached 17 million, which was up 25% from the year before.

The unknowns ahead: What about data centers?

The construction of new data centers, in part to serve the explosive growth of artificial intelligence, is drawing a lot of attention to future energy demand and to the uncertainty ahead.

Data centers are increasing electricity demand in some locations, such as northern Virginia, Dallas, Phoenix, Chicago and Atlanta. The future electricity demand growth from data centers is still unclear, though, meaning the effects of data centers on electric rates and power system emissions are also uncertain.

However, AI is not the only reason to watch for increased electricity demand: The U.S. can expect growing electricity demand for industrial processes and electric vehicles, as well as the overall transition from using oil and gas for heating and appliances to using electricity that continues across the country.

![]()

Valerie Thomas receives funding from the US Department of Energy

– ref. How the US cut climate-changing emissions while its economy more than doubled – https://theconversation.com/how-the-us-cut-climate-changing-emissions-while-its-economy-more-than-doubled-268763