Source: The Conversation – UK – By Rikke Lie Halberg, PhD Candidate in History, Lund University

When Nazi Germany began its occupation of Denmark in April 1940, Greenland suddenly found itself cut off from its colonial power and thrust into the centre of North Atlantic wartime strategy. The US took control of Greenland temporarily, establishing bases and defence perimeters there to prevent Germany from using the island.

More than 80 years later, Donald Trump invoked that moment at the World Economic Forum in Davos. In his speech on January 21, the US president claimed his country “gave Greenland back” to Denmark after the second world war. This history, Trump implied, still gives the US a claim to Greenland today.

Trump’s claim rests on a selective reading of wartime history. It also reflects a colonial and imperial way of thinking about territory, sovereignty and ownership. To understand why his claim is misleading, it helps to follow the sequence of agreements that governed Greenland before, during and after the war.

In 1916, Denmark sold its Caribbean colony, the Danish West Indies, to the US (which then changed its name to the US Virgin Islands). That same convention included an explicit American declaration that the US would not object to Denmark extending its “political and economic interests to the whole of Greenland”. As one colony was transferred, sovereignty over another was reaffirmed.

But during the second world war, wartime circumstances and US strategic needs drove another agreement between Denmark and the US that allowed the Americans to assume responsibility for Greenland’s defence. That arrangement was formalised in the 1941 Greenland Defense Agreement, drawn up by the American state department and signed by Henrik Kauffmann, the Danish envoy in Washington.

The agreement explicitly stated that the US government “fully recognizes the sovereignty” of Denmark over Greenland. It added that the US is “animated by sentiments of the completest friendliness for Denmark and believes that by taking these steps, it is safeguarding the eventual re-establishment of the normal relationship between Greenland and the Kingdom of Denmark”.

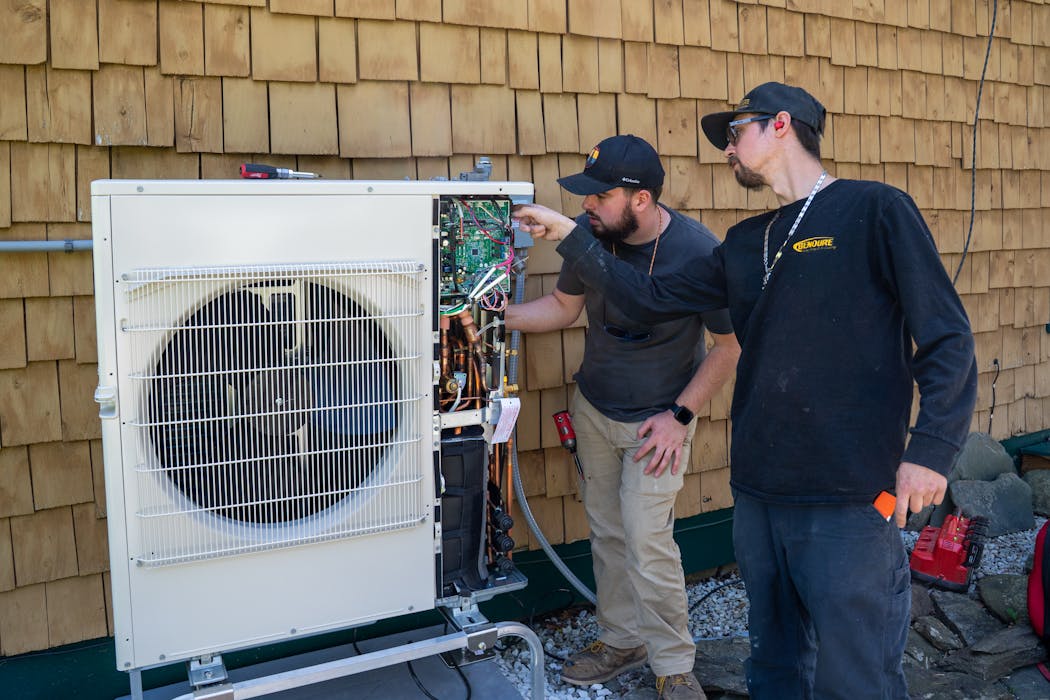

In practice, the US did defend Greenland during the war. It built airstrips and military installations there, while also running patrols and integrating the island into wider allied logistics.

Michelle van Dijk / Shutterstock

In 1945, after the end of the war, Kauffmann wrote a diplomatic note to the US. He declared that it had “been a source of great satisfaction to the Danish people” that Denmark had an “opportunity to contribute to the war effort through the placing of Danish territory at the disposal of the United States in the fight against the common enemy”.

Kauffmann added that Denmark did not wish “to receive any payment” for the US military’s use of Greenland during the war. The note framed Denmark’s wartime cooperation as a voluntary contribution, again affirming Danish sovereignty over Greenland.

The wartime arrangement was later translated into a post-war security relationship. In 1951, with Denmark and the US now formal allies within the UN and Nato, the two countries concluded a new defence agreement. This granted the US extensive and permanent military rights in Greenland, now within the framework of peacetime alliance politics.

The post-war period represented a legal consolidation of a US presence in Greenland that had begun under wartime exception. This included the construction of installations such as the Thule Air Base (now Pituffik Space Base) on Greenland’s north-west coast. The base became a cornerstone of US strategic operations in the Arctic, and remains the only active American base in Greenland today.

The construction and expansion of Thule entailed the forced relocation of the local Inuit population in 1953. This move was later recognised as unjust by the Danish court system, leading to compensation awarded by the Danish state in 1999.

Colonial entanglements

These arrangements stabilised Danish sovereignty over Greenland and bolstered the island’s security. But they left the colonial relationship itself largely unexamined. In 1953, in the context of emerging UN norms on decolonisation, Greenland’s colonial status was formally lifted, and the territory was integrated into the Danish state.

This administrative transformation allowed Denmark to present its relationship with Greenland as post-colonial, without engaging in a broader reckoning with the political, cultural and economic legacies of colonial rule. Subsequent reforms can be understood as belated attempts to address this unresolved colonial relationship.

These include home rule in 1979, which transferred responsibility for most domestic affairs from Denmark to a Greenlandic parliament. Self-government in 2009 further expanded Greenland’s political autonomy and recognised Greenlanders as a people under international law.

Recent developments underline just how new the participation of Greenlanders in their own affairs is. The inclusion of Greenland’s foreign minister, Vivian Motzfeldt, in high-level January talks in Washington marks a clear break with earlier practice, where Greenland’s strategic future was negotiated without Greenlandic representatives at the table.

Trump’s attempt to revive imperial language of ownership sharpens the contrast between older colonial ways of thinking and emerging efforts to include Greenlandic political voices in discussions over their future. On this terrain, the contest is no longer only about the past, but also which parties will be part of the discussion about the future.

![]()

Rikke Lie Halberg receives funding from Lund University for her PhD research on the Fireburn revolt in the Danish West Indies.

– ref. Did the US ever ‘give back’ Greenland to Denmark, as Trump claims? – https://theconversation.com/did-the-us-ever-give-back-greenland-to-denmark-as-trump-claims-274335