Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Cameron Dodd, PhD Student in Evolutionary Biology and Taxonomy, The University of Western Australia

Australia is home to more than 60 species of carnivorous marsupials in the family Dasyuridae. Almost a quarter of those have only been scientifically recognised in the past 25 years.

Other than the iconic Tasmanian devil, chances are most of these small, fascinating species have slipped under your radar. One of the rarest and most elusive is the kultarr (Antechinomys laniger), a feisty insect-eater found in very low numbers across much of the outback.

To the untrained eye, the kultarr looks very much like a hopping mouse, with long legs, a long tail and a tendency to rest on its hind legs. However, it runs much like a greyhound – but its tiny size and high speed makes it look like it’s hopping.

Kultarr or kultarrs?

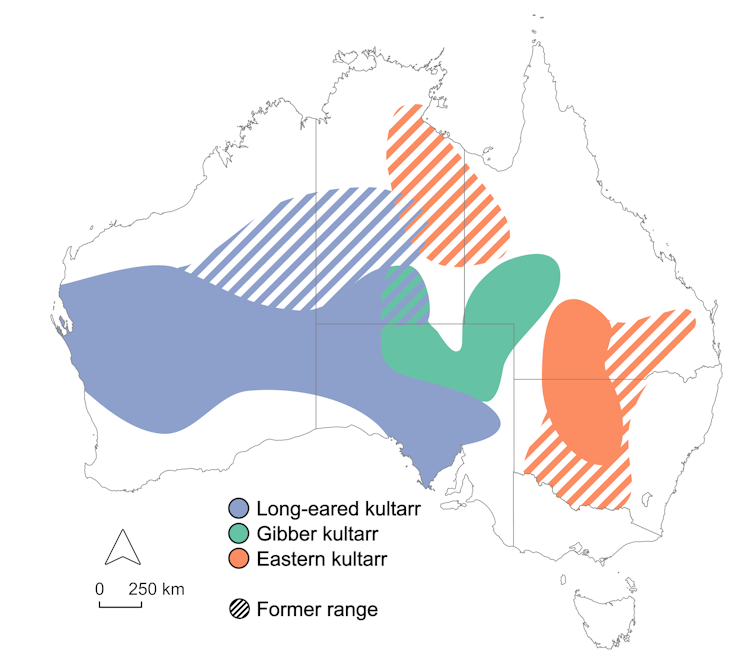

Until now, the kultarr was thought to be a single widespread species, ranging from central New South Wales to the Carnarvon Basin on Australia’s west coast. However, a genetic study in 2023 suggested there could be more than one species.

With backing from the Australian Biological Resources Study, our team of researchers from the University of Western Australia, Western Australian Museum and Queensland University of Technology set out to investigate.

We travelled to museums in Adelaide, Brisbane, Darwin, Melbourne, Sydney and Perth to look at every kultarr that had been collected by scientists over the past century. By combining detailed genetic data with body and skull measurements, we discovered the kultarr isn’t one widespread species, but three distinct species.

Three species of kultarrs

The eastern kultarr (A. laniger) is the smallest of the three, with an average body length of about 7.5cm. It’s darker in colour than its relatives, and while its ears are still big, they are nowhere near as big as those of the other two species.

The eastern kultarr is now found on hard clay soils around Cobar in central NSW and north to around Charleville in southern Queensland.

Pat Woolley

The gibber kultarr (A. spenceri) is the largest and stockiest, with an average body length of around 9cm. They are noticeably chunkier than the other two more dainty species, with big heads, thick legs and much longer hindfeet.

As its name suggests, the gibber kultarr is restricted to the extensive stony deserts or “gibber plains” in southwest Queensland and northeast South Australia.

Ken Johnson

The long-eared kultarr (A. auritus) is the middle child in terms of body size, but its ears set it apart. They’re nearly as long as its head.

It’s found in patchy populations in the central and western sandy deserts, living on isolated stony plains.

Ken Johnson

Are they threatened?

All three species of kultarr are hard to find, making it difficult to confidently estimate population sizes and evaluate extinction risk. The long-eared and gibber kultarrs don’t appear to be in immediate danger, but land clearing and invasive predators such as cats and foxes have likely affected their numbers.

Cameron Dodd

The eastern kultarr, however, is more of a concern. By looking at museum specimens going back all the way to the 1890s, we found it was once much more widespread.

Historic records suggest the eastern kultarr used to occur across the entirety of arid NSW and even spread north through central Queensland and into the Northern Territory. We now think this species may be extinct in the NT and parts of northwest Queensland.

What’s next?

To protect kultarrs into the future, we need targeted surveys to confirm where each species still survives, especially the eastern kultarr, whose current range may be just a shadow of its former extent. With better knowledge, we can prioritise conservation actions where they’re most needed, and ensure these remarkable, long-legged hunters don’t disappear before we truly get to know them.

Australia still has many small mammal species that haven’t been formally described. Unless we identify and name them, they remain invisible in conservation policy.

Taxonomic research like this is essential – we can’t protect what we don’t yet know exists. And without action, some species may disappear before they’re ever officially recognised.

The authors wish to acknowledge the important contributions of Adjunct Professor Mike Westerman at La Trobe University to the research discussed in this article.

![]()

Cameron Dodd receives funding from the Australian Biological Resources Study and Society of Australian Systematic Biologists.

Andrew M. Baker receives funding from the Federal Government, State Governments, Australian Biological Resources Study and various Industry sources.

Kenny Travouillon receives funding from Australian Biological Resources Study.

Linette Umbrello receives funding from the Australian Biological Resources Study (ABRS) National Taxonomy Research Grant Program (NTRGP)

Renee Catullo does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Australia’s cutest mammal is now Australia’s cutest three mammals – https://theconversation.com/australias-cutest-mammal-is-now-australias-cutest-three-mammals-260006