Source: The Conversation – USA (3) – By Art Jipson, Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Dayton

Vance Boelter, who allegedly shot Melissa Hortman, a Democratic Minnesota state representative, and her husband, Mark Hortman, on June 14, 2025, studied at Christ for the Nations Institute in Dallas. The group is a Bible school linked to the New Apostolic Reformation, or NAR.

The NAR is a loosely organized but influential charismatic Christian movement that shares similarities with Pentecostalism, especially in its belief that God actively communicates with believers through the Holy Spirit. Unlike traditional Pentecostalism, however, the organization emphasizes modern-day apostles and prophets as authoritative leaders tasked with transforming society and ushering in God’s kingdom on Earth. Prayer, prophecy and worship are defined not only as acts of devotion but as strategic tools for advancing believers’ vision of government and society.

After the shooting, the Christ for the Nations Institute issued a statement “unequivocally” denouncing “any and all forms of violence and extremism.” It stated: “Our organization’s mission is to educate and equip students to spread the Gospel of Jesus Christ through compassion, love, prayer, service, worship, and value for human life.”

But the shooting has drawn attention to the school and the larger Christian movement it belongs to. One of the most important aspects of NAR teachings today is what is called “the Seven Mountain Mandate.”

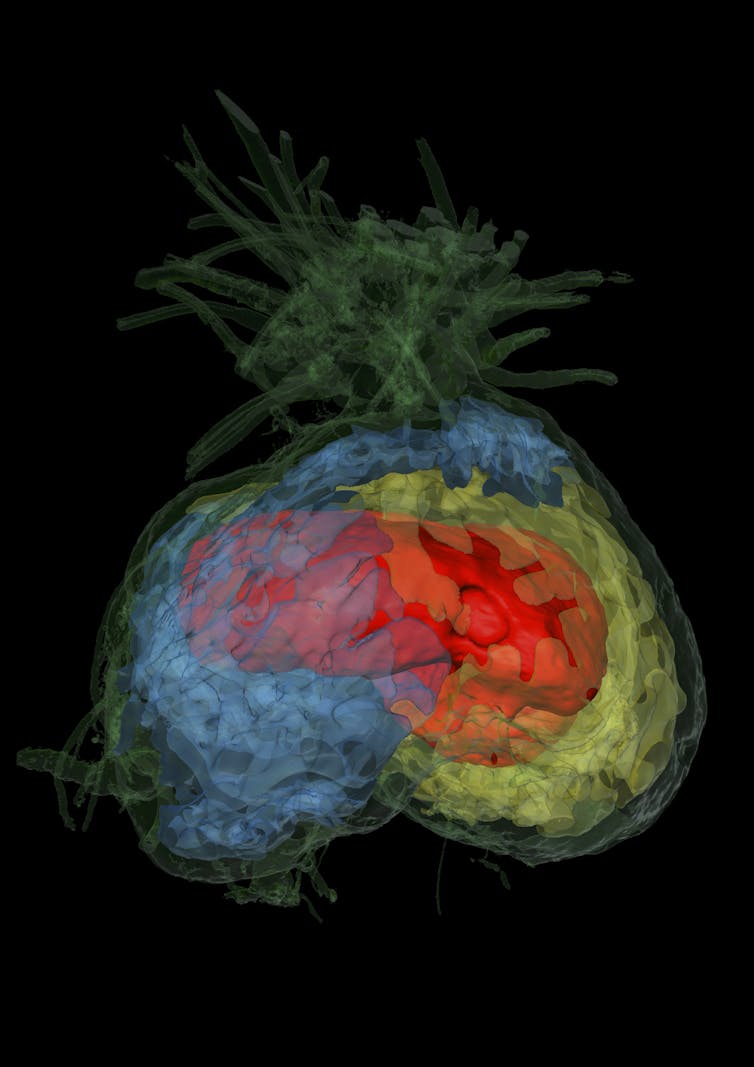

The Seven Mountain Mandate calls on Christians to gain influence, or “take dominion,” over seven key areas of culture: religion, family, education, government, media, business and the arts.

With over three decades of experience studying extremism, I offer a brief overview of the history and core beliefs of the Seven Mountain Mandate.

‘Dominion of Christians’

The Seven Mountain concept was originally proposed in 1975 by evangelical leader Bill Bright, the founder of Campus Crusade for Christ. Now known as “Cru,” the Campus Crusade for Christ was founded as a global ministry in 1951 to promote Christian evangelism, especially on college campuses.

United by a shared vision to influence society through Christian values, Bright partnered with Loren Cunningham, the founder of Youth With A Mission, a major international missionary training and outreach organization, in the 1970s.

The Seven Mountain Mandate was popularized by theologian Francis Schaeffer, who linked it to a larger critique of secularism and liberal culture. Over time, it evolved.

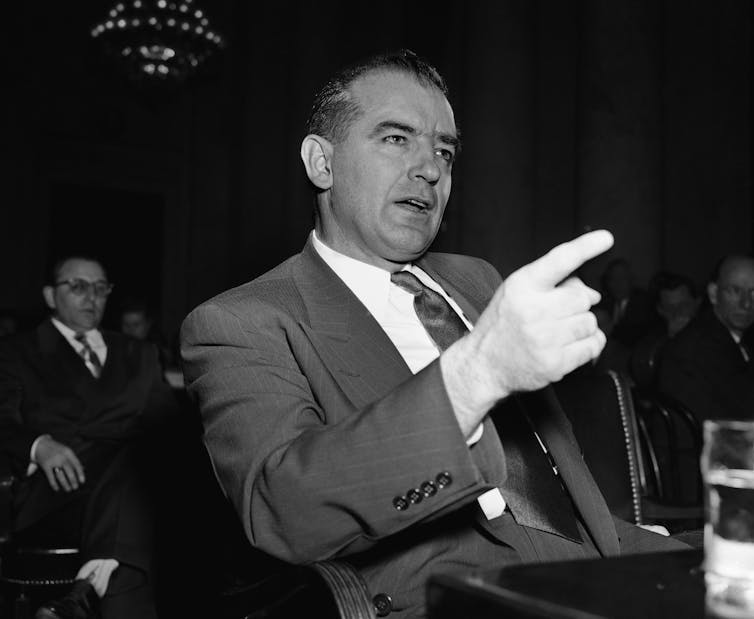

C. Peter Wagner, a former seminary professor who helped organize and name the New Apostolic Reformation, is often regarded as the theological architect of the group. He developed it into a call for dominion. In his 2008 book “Dominion! How Kingdom Action Can Change the World,” he urged Christians to take authoritative control of cultural institutions.

For Wagner, “dominion theology” – the idea that Christians should have control over all aspects of society – was a call to spiritual warfare, so that God’s kingdom would be “manifested here on earth as it is in heaven.”

Doctorg via Wikimedia Commons

Since 1996, Bill Johnson, a senior leader of Bethel Church, and Johnny Enlow, a self-described prophet and Seven Mountain advocate, among others, have taken the original idea of the Seven Mountain Mandate and reshaped it into a more aggressive, political and spiritually militant approach. Spiritual militancy reflects an aggressive, us-vs.-them mindset that blurs the line between faith and authoritarianism, promoting dominion over society in the name of spiritual warfare.

Their version doesn’t just aim to influence culture; it frames the effort as a spiritual battle to reclaim and reshape the nation according to their vision of God’s will.

Lance Wallnau, another Christian evangelical preacher, televangelist, speaker and author, has promoted dominion theology since the early 2000s. During the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Wallnau, along with several prominent NAR figures, described Donald Trump as anointed by God to reclaim the “mountain” of government from demonic control.

In their book “Invading Babylon: The 7 Mountain Mandate,” Wallnau and Johnson explicitly call for Christian leadership as the only antidote to perceived moral decay and spiritual darkness.

The beliefs

Sometimes referred to as Seven Mountains of Influence or Seven Mountains of Culture, the seven mountains are not neutral domains but seen as battlegrounds between divine truth and demonic deception.

Adherents believe that Christians are called to reclaim these areas through influence, leadership and even, if necessary, the use of force and to confront demonic political forces, as religion scholar Matthew Taylor demonstrates in his book “The Violent Take It By Force.”

Diverse perspectives and interpretations surround the rhetoric and actions associated with the New Apostolic Reformation. Some analysts have pointed out how the NAR is training its followers for an active confrontation. Other commentators have said that the rhetoric calling for physical violence is anti-biblical and should be denounced.

NAR-aligned leaders have framed electoral contests as struggles between “godly” candidates and those under the sway of “satanic” influence.

Similarly, NAR prophet Cindy Jacobs has repeatedly emphasized the need for “spiritual warfare” in schools to combat what she characterizes as “demonic ideologies” such as sex education, LGBTQ+ inclusion or discussions of systemic racism.

In the NAR worldview, cultural change is not merely political or social but considered a supernatural mission; opponents are not simply wrong but possibly under the sway of demonic influence. Elections become spiritual battles.

This belief system views pluralism as weakness, compromise as betrayal, and coexistence as capitulation. Frederick Clarkson, a senior research analyst at Political Research Associates, a progressive think tank based in Somerville, Massachusetts, defines the Seven Mountain Mandate as “the theocratic idea that Christians are called by God to exercise dominion over every aspect of society by taking control of political and cultural institutions.”

The call to “take back” the culture is not metaphorical but literal, and believers are encouraged to see themselves as soldiers in a holy war to dominate society. Some critics argue that NAR’s call to “take back” culture is about literal domination, but this interpretation is contested.

Many within the movement see the language of warfare as spiritually focused on prayer, evangelism and influencing hearts and minds. Still, the line between metaphor and mandate can blur, especially when rhetoric about “dominion” intersects with political and cultural action. That tension is part of an ongoing debate both within and outside the movement.

Networks that spread the beliefs

This belief system is no longer confined to the margins. It is spread widely through evangelical churches, podcasts, YouTube videos and political networks.

It’s hard to know exactly how many churches are part of the New Apostolic Reformation, but estimates suggest that about 3 million people in the U.S. attend churches that openly follow NAR leaders.

At the same time, the Seven Mountain Mandate doesn’t depend on centralized leadership or formal institutions. It spreads organically through social networks, social media – notably podcasts and livestreams – and revivalist meetings and workshops.

André Gagné, a theologian and author of “American Evangelicals for Trump: Dominion, Spiritual Warfare, and the End Times,” writes about the ways in which the mandate spreads by empowering local leaders and believers. Individuals are authorized – often through teachings on spiritual warfare, prophetic gifting, and apostolic leadership – to see themselves as agents of divine transformation in society, called to reclaim the “mountains,” such as government, media and education, for God’s kingdom.

This approach, Gagné explains, allows different communities to adapt the action mandate to their unique cultural, political and social contexts. It encourages individuals to see themselves as spiritual warriors and leaders in their domains – whether in business, education, government, media or the arts.

Small groups or even individuals can start movements or initiatives without waiting for top-down directives. The only recognized authorities are the apostles and prophets running the church or church network the believers attend.

The framing of the Seven Mountain Mandate as a divinely inspired mission, combined with the movement’s emphasis on direct spiritual experiences and a specific interpretation of scripture, can create an environment where questioning the mandate is perceived as challenging God’s authority.

Slippery slope

These beliefs have increasingly fused with nationalist rhetoric and conspiracy theories.

Paul Becker/Becker1999 via Flickr, CC BY

A powerful example of NAR political rhetoric in action is the rise and influence of the “Appeal to Heaven” flags. For those in the New Apostolic Reformation, these flags symbolize the belief that when all earthly authority fails, people have the right to appeal directly to God’s authority to justify resistance.

This was evident during the Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol insurrection, when these flags were prominently displayed.

To be clear, its leaders are not calling for violence but rather for direct political engagement and protest. For some believers, however, the calls for “spiritual warfare” may become a slippery slope into justification for violence, as in the case of the alleged Minnesota shooter.

Understanding the Seven Mountain Mandate is essential for grasping the dynamics of contemporary efforts to align government and culture with a particular vision of Christian authority and influence.

![]()

Art Jipson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. What is the ‘Seven Mountain Mandate’ and how is it linked to political extremism in the US? – https://theconversation.com/what-is-the-seven-mountain-mandate-and-how-is-it-linked-to-political-extremism-in-the-us-260034