Source: The Conversation – in French – By Bénédicte Aldebert, Professeure des Universités, Entrepreneuriat & Innovation, IAE Aix-Marseille Graduate School of Management – Aix-Marseille Université

Comment rebondir après un échec entrepreneurial ? Pour les dirigeants des entreprises en liquidation, l’injonction à repartir vite n’est pas si simple à remplir. Il n’est pas sûr qu’on rebondisse bien, seul. Mieux vaut être accompagné pour repartir du bon pied.

Les défaillances d’entreprises continuent d’augmenter, de 55 000 cas en 2022 à plus de 66 000 cas en 2024. Une part significative a conduit à la liquidation judiciaire. Cet événement souvent vécu comme traumatique peut mener à des conséquences parfois désastreuses sur la vie de l’entrepreneur, mais aussi sur sa santé mentale – la perte de confiance et de légitimité pouvant déboucher sur un burn-out et parfois même un suicide.

Dans une société contemporaine qui valorise les success stories des entrepreneurs, la décision d’une liquidation judiciaire par le tribunal tombe comme un couperet. Les entrepreneurs ayant subi une liquidation sont parfois assimilés à de mauvais gestionnaires ou à des personnes imprudentes. Cette stigmatisation peut limiter l’accès à de nouvelles opportunités de financement et de partenariat pour un nouveau projet. Ce sentiment d’exclusion du monde des affaires et la baisse de l’estime de soi peuvent alors conduire à une autostigmatisation, où l’entrepreneur intègre et intériorise ces jugements négatifs portés par son entourage ou la société.

À lire aussi :

Succès, échecs : pourquoi le rôle du mérite est-il surévalué ?

Deux mille deux cent vingt entrepreneurs aidés

Aider les entrepreneurs ayant subi une liquidation à se reconstruire sur le plan personnel et professionnel est la raison d’être de plusieurs dispositifs d’intérêt général à caractère social, comme l’association 60 000 Rebonds. Avec 2 020 entrepreneurs ayant rebondi depuis sa création et 1850 bénévoles mobilisés, l’accompagnement de l’association repose sur une combinaison d’approches individuelles et collectives, incluant coaching, mentorat et ateliers thématiques.

Notre enquête menée en 2024, auprès de 216 entrepreneurs accompagnés par l’association, a pu mettre en lumière un état des lieux des entrepreneurs ayant rebondi, les obstacles à leur rebond et les leviers facilitant la reconstruction de ces entrepreneurs après une liquidation.

L’échec, une expérience individuelle

Premier constat issu de cette enquête : 67 % des rebonds sont réalisés dans le salariat contre seulement 33 % dans l’entrepreneuriat. Parmi celles et ceux qui se sont relancé·e s dans l’aventure entrepreneuriale, 71 % ont invoqué le désir d’autonomie professionnelle et d’indépendance dans leur décision. Pour 82 % des premiers, la raison principale de ce choix est le besoin de se sécuriser financièrement après cet épisode éprouvant.

Loin d’être uniquement entrepreneurial, le rebond peut en effet prendre plusieurs formes et implique, comme sa définition l’indique, une remise en mouvement après un choc. Mais qu’est-ce qui peut empêcher cette remise en mouvement ?

Une inquiétante perte de confiance en soi

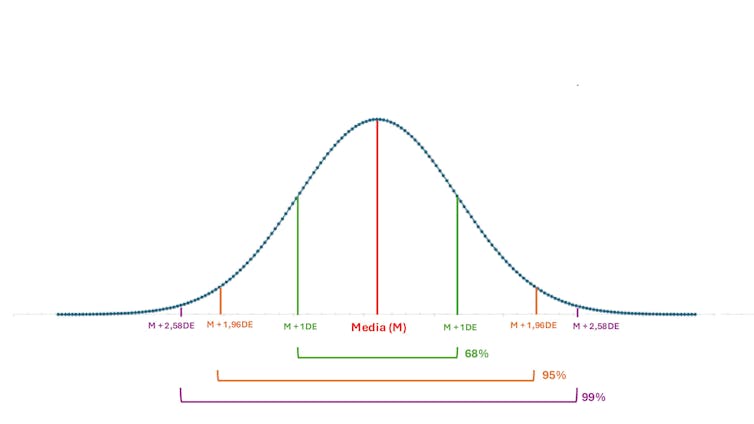

En 2021, le principal frein au rebond était le manque d’argent pour 32,5 % d’entre eux et la confiance en soi pour 28,9 %. En 2024, la situation s’est renversée : 39 % des répondants ont évoqué un manque de confiance en soi comme frein majeur à leur rebond et 26 % ont cité des difficultés financières comme obstacle au rebond.

Si ce dernier chiffre souligne l’impact économique indiscutable de la liquidation sur les entrepreneurs, les chiffres de l’enquête 2024 attestent aussi d’une prise de conscience.

Perdre son entreprise est bel et bien un traumatisme au cours duquel l’amour-propre et la volonté d’aller de l’avant se trouvent ébranlés. Cet impact psychologique peut laisser des traces profondes – honte, sentiment d’inutilité, impression d’avoir perdu sa légitimité – et influence la manière dont on entrevoit les chemins qui nous sont offerts.

L’élan du collectif

En 2024, le dispositif le plus apprécié est devenu l’accompagnement collectif – et en particulier les groupes d’échanges et de développement (70 %) – alors qu’il n’était qu’en quatrième position en 2021. Si le coaching individuel reste néanmoins en position favorable, ces données mettent en lumière de nouvelles attentes prioritaires chez les entrepreneurs accompagnés : sortir de l’isolement, normaliser l’échec et retrouver un sentiment d’appartenance au sein d’un groupe de personnes ayant vécu la même expérience.

L’enquête enseigne ainsi que si sortir de la spirale négative de l’échec nécessite un travail de fond sur soi, cela est rendu possible grâce à un environnement soutenant, bienveillant et structurant. À travers ses multiples espaces de confiance et de bienveillance, l’accompagnement proposé par 60 000 Rebonds permet à l’entrepreneur ayant vécu une liquidation judiciaire de se sentir sécurisé, valorisé et reconnecté à un collectif.

Comprendre le rebond

Rebondir, ce n’est pas simplement retrouver un emploi ou lancer une nouvelle entreprise. C’est, d’abord, prendre la mesure du choc et de la perte vécus. Le rebond est en effet souvent précédé d’un processus de deuil, avec ses étapes : déni, colère, marchandage, dépression, acceptation. Mais si l’expérience de cette perte reste une expérience intime et personnelle, le rebond, quant à lui, représente un enjeu collectif. Car c’est bien dans le lien tissé avec les autres que l’entrepreneur ayant vécu une liquidation judiciaire va pouvoir retrouver un rapport positif à lui-même, réactiver son sentiment de compétence, d’autonomie et créer un nouveau récit pour lui-même.

Notre étude plaide donc pour un élargissement des dispositifs d’accompagnement post-liquidation, à l’image de ce que fait 60 000 Rebonds. Elle permet également de souligner notre responsabilité collective ainsi que celle de nos institutions dans la stigmatisation de l’échec. Si l’écosystème entrepreneurial qui vise à accompagner la création et la croissance des entreprises est en pleine expansion depuis plus de vingt ans, les initiatives politiques – issues notamment de la loi Pacte (2019) – pour intégrer l’échec et le rebond comme faisant partie du processus entrepreneurial sont encore timides.

Changer de regard sur l’échec ne consiste pas seulement à changer de regard sur l’entrepreneuriat. C’est également un changement de posture à mettre en œuvre dans la transmission de nos apprentissages, où l’humilité et le droit à l’erreur feront partie de nos standards et où la capacité à apprendre des échecs individuels et collectifs fera partie de nos enseignements scolaires et universitaires.

![]()

Nous traitons du sujet de la défaillance d’entreprises en lien avec l’association 60000 rebonds que nous citons dans l’article.

Nous traitons du sujet de la défaillance d’entreprises en lien avec l’association 60000 rebonds que nous citons dans l’article.

Nous traitons du sujet de la défaillance d’entreprises en lien avec l’association 60000 rebonds que nous citons dans l’article.

– ref. Le rebond, après une liquidation judiciaire, une affaire collective ? – https://theconversation.com/le-rebond-apres-une-liquidation-judiciaire-une-affaire-collective-256658