Source: The Conversation – USA – By Robin Brewer, Associate Professor of Information, University of Michigan

Artificial intelligence is a lively topic of conversation in schools and workplaces, which could lead you to believe that only younger people use it. However, older Americans are also using AI. This raises the questions of what they’re doing with the technology and what they think of it.

I’m a researcher who studies older age, disability and technology use. I partnered with the University of Michigan’s National Poll on Healthy Aging to survey nearly 3,000 Americans over the age of 50. We asked them whether and how they use AI and what concerns they have about using it.

Of the older people we surveyed, 55% responded that they had used some type of AI technology that they can speak to, like Amazon’s Alexa voice assistant, or type to, like OpenAI’s ChatGPT chatbot. Voice assistants were overwhelmingly more popular than text chatbots: Half of them reported using a voice assistant within the past year, compared to 1 in 4 who used a chatbot.

Popular, among some

Independent living continues to be a major goal of older Americans as they either do not want to or are unable to afford to live in long-term care communities, and AI may be a tool to support this goal. Our findings show that older adults who use AI in their homes find it helpful for living independently and safely.

They mostly used these technologies for entertainment or searching for information, but some of their responses show more creative uses, such as generating text, creating images or planning vacations.

Nearly 1 in 3 older adults reported using AI-powered home security devices, including doorbells, outdoor cameras and alarm systems. Nearly all of those people – 96% – felt safer using them.

While there has been some concern about privacy when using cameras indoors to monitor older people, cameras aimed outdoors seem to provide a sense of security for those who may be aging in their homes alone or without family nearby. Of the 35% of older adults who reported using AI-powered home security systems, 96% said they were beneficial.

O2O Creative/E+ via Getty Images

However, when we dove into which older adults are using AI, we saw that demographics matter. Specifically, those in better health, with more education and higher incomes were more likely to have used AI-powered voice assistants and home security devices in the past year. This pattern seems to follow adoption trends of other technologies such as smartphones.

Trusting AI is tricky

As more information about AI’s accuracy emerges, so do questions about whether people can trust it. Our survey results show that older Americans are split on whether to trust content that was generated by AI: 54% said they trust AI, and 46% said they do not. People who trusted AI more were more likely to have used some type of AI technology within the past year.

Further, AI-generated content can sometimes look correct but be inaccurate. Being able to identify incorrect information from AI is important for assessing whether and how to use AI-generated search results or chatbots. However, only half of the older people surveyed were confident that they could identify whether content from AI was incorrect.

More educated users were more likely to say they felt confident they could spot inaccuracies. Conversely, older adults who reported lower levels of physical and mental health were less likely to trust AI-generated content.

What to do?

Together, these findings repeat a common cycle of technology adoption that is pervasive even among younger demographics, where more educated and healthy people are among the first to adopt and be aware of newer technologies. This raises questions about how to best reach all older people about the benefits and risks of AI.

How can older people who are not AI users get support for learning more so that they can make informed decisions about whether to use it? How can institutions develop better training and awareness tools so that older people who trust AI avoid trusting it too much or inappropriately using AI to make important decisions without understanding the risks?

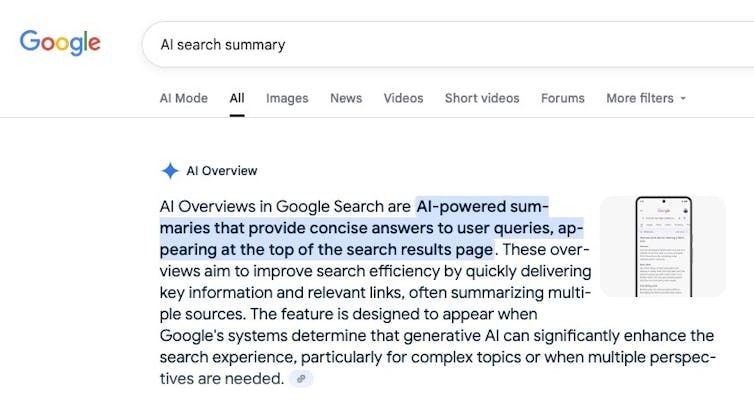

Our survey results highlight potential starting points for developing AI literacy tools for older adults. Nine in 10 older people wanted to know when information had been generated by AI. We are starting to see AI labels on search engine results, such as Google search’s AI snippets.

Screenshot by The Conversation

Michigan and other states have adopted policies for disclosing AI content in political ads, but these notices could be made more visible in other contexts, such as nonpolitical advertising and on social media. Further, nearly 80% of older people wanted to learn more about AI risks – where might it go wrong and what to do about it.

Policymakers can focus on enforcing AI notices that signal content was generated by AI, particularly at a critical time when the U.S. is considering revising its AI policies to do just the opposite – removing language about risk, discrimination and misinformation – based on a new executive order.

Overall, our findings show that AI can support healthy aging. However, overtrust and mistrust of AI could be addressed with better training tools and policies to make risks more visible.

![]()

Robin Brewer receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. She has previously received funding from Google, the Retirement Research Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Transportation.

– ref. Older Americans are using AI − study shows how and what they think of it – https://theconversation.com/older-americans-are-using-ai-study-shows-how-and-what-they-think-of-it-262411