Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Lincoln Mitchell, Lecturer, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University

Top Republicans and Democrats alike are talking about the sudden rise of 33-year-old Zohran Mamdani, a state representative who won the Democratic mayoral primary in New York on June 24, 2025, in a surprising victory over more established politicians.

While President Donald Trump quickly came out swinging with personal attacks against Mamdani, some establishment Democratic politicians say they are concerned about how the democratic socialist’s progressive politics could harm the broader Democratic Party and cause it to lose more centrist voters.

New York is a unique American city, with a diverse population and historically liberal politics. So, does a primary mayoral election in New York serve as any kind of harbinger of what could come in the rest of the country?

Amy Lieberman, a politics and society editor at The Conversation U.S., spoke with Lincoln Mitchell, a political strategy and campaign specialist who lectures at Columbia University, to understand what Mamdani’s primary win might indicate about the direction of national politics.

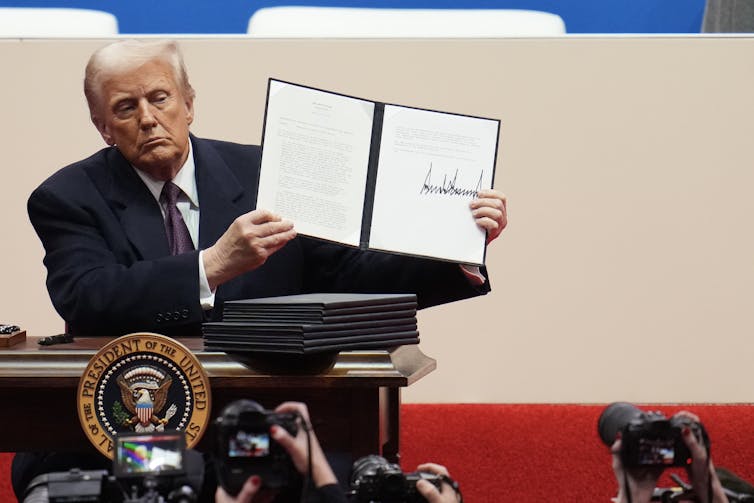

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

Does Mamdani’s primary win offer any indication of how the Democratic Party might be transforming on a national level?

Mamdani’s win is clearly a rebuke of the more corporate wing of the Democratic Party. I know there are people who say that New York is different from the rest of the country. But from a political perspective, Democrats in New York are less different from Democrats in the rest of country than they used to be.

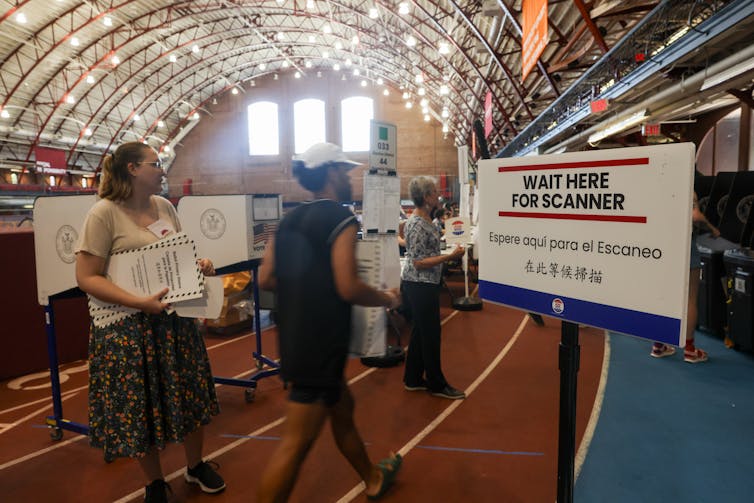

That’s because the rest of America is so much more diverse than it used to be. But if you look at progressive politicians now in the House of Representatives and state legislatures, they are being elected from all over – not just in big cities like New York anymore.

Andrew Cuomo, the former governor of New York, ran an absolutely terrible mayoral campaign. He tried to build a political coalition that is no longer a winning one, which was made up of majorities of African Americans, outer-borough white New Yorkers and orthodox and conservative Jews. Thirty or 40 years ago, that was a powerful coalition. Today, it could not make up a majority.

Mamdani visualized and created what a 2025 progressive coalition looks like in New York and recognized that it is going to look different than the past. Mamdani’s coalition was based around young, white people – many of them with college degrees who are worried about affordability – ideological lefties and immigrants from parts of the Global South, including the Caribbean and parts of Africa, South Asia and South America.

When you say a new kind of political coalition, what policy priorities bring Mamdani’s supporters together?

Mamdani reframed what I would call redistributive economic policies that have long been central to the progressive agenda. A pillar of his campaign is affordability – a brilliant piece of political marketing because who is against affordability? He came up with some affordability-related policies that got enough buzz, like promising free buses. Free buses are great, but it won’t help most working and poor New Yorkers get to work – they take the subway.

He has been very critical of Israel and has weathered charges of antisemitism.

In the older New York, progressive politicians such as the late Congressman Charlie Rangel were very hawkish on Israel.

What Mamdani understood is that in today’s America, the progressive wing of the Democratic Party does not care if somebody is, sounds like or comes close to being antisemitic. For those people, calling someone antisemitic sounds Trumpy, and they understand it as a right-wing hit, rather than the legitimate expression of concerns from Jewish people. Some liberals think that claims of antisemitism are simply something done just by those on the right to damage or discredit progressive politicians, but antisemitism is real.

Therefore, Mamdani’s record on the Jewish issue did not hurt him in the campaign, but he needs to build bridges to Jewish voters, or he will not be able to govern New York City.

How else did Mamdani appeal to a base of supporters?

He got the support of “limousine liberals” – including rich, high-profile, progressive people. His supporters include Ella Emhoff, a model and the stepdaughter of Kamala Harris, and the actress Cynthia Nixon, but there were many others. Supporting Mamdani became stylish – almost de rigueur – among certain segments of affluent New York.

Mamdani is also a true New Yorker and the voice of a new kind of immigrant. His parents are from Uganda and India. But he is also the child of extreme privilege – his mother, Mira Nair, is a well-known filmmaker, and his father is an accomplished professor. Mamdani went to top schools in New York and knows how to play in elite circles and with white people. He is a Muslim man whose roots are in the Global South, but he is not threatening because he knows how to speak their language.

To people of color and immigrants, Mamdani is also one of them. Because of Mamdani’s interesting background, he brought the limousine liberals together with the aunties from Bangladesh.

Finally, on the charisma scale, Mamdani was so far ahead of other Democratic candidates. Who is going to make better TikTok videos – the good-looking, young man whose mother is a world-famous movie producer, or the older guy who is a loving father and husband but gives off dependable dad, rather than hip young guy, vibes?

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Is New York City so distinct that you cannot compare politics there to what happens nationwide?

I think that nationwide or at the state level there is a potential for something similar to a Mamdani coalition, but not a Mamdani coalition exactly. But in a place like Oklahoma, there are people who are in bad economic shape and who will also respond positively to an affordability-focused, Democratic political campaign. Mamdani remade a progressive New York coalition for this moment. Other progressives politicians should copy the spirit of that and reimagine a winning coalition in their city, state or district.

When Trump was campaigning, he focused at least on making groceries cheaper. Mamdani is one of the few Democrats who took the affordability issue back from Trump and addressed it head on and in a much more honest and relevant way. Trump has the phrase, “Make America Great Again!” That’s a popular slogan on baseball caps for Trump supporters.

If Mamdani wanted to make a baseball cap, he could just print “Affordability” on it. Boom.

Other Democratic politicians can take that approach of affordability and reframe it in a way that works in Kansas City or elsewhere.

![]()

Lincoln Mitchell supported Brad Lander in the primary election.

– ref. How Zohran Mamdani’s win in the New York City mayoral primary could ripple across the country – https://theconversation.com/how-zohran-mamdanis-win-in-the-new-york-city-mayoral-primary-could-ripple-across-the-country-259951