Source: – By Brian Bossak, Professor of Public Health, College of Charleston

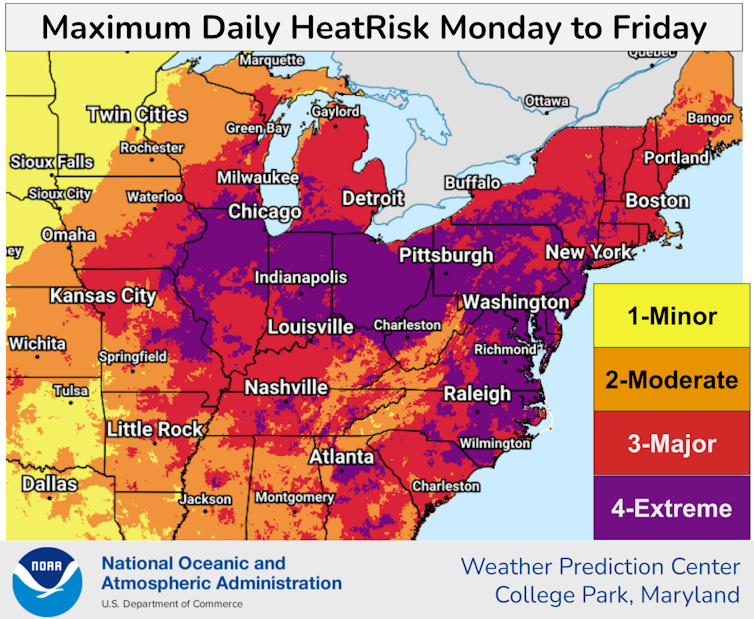

Summer is just getting started, and millions of people are under heat advisories as a major heat wave spreads across large parts of the central and eastern U.S. in June 2025.

For many people, summer is their favorite season, a time for cookouts, beach trips and other outdoor activities. However, summer also brings the risk of dangerously high temperatures and humidity.

In the U.S., hundreds of people working or playing outside – even those who seem healthy – succumb to heat-related illnesses each year. Older adults and people in areas that historically haven’t needed air conditioning tend to see the highest rates of illnesses during heat waves, as Chicago saw in 1995 when at least 700 people died in a heat wave.

NOAA Weather Prediction Center

Even in places where heat is recognized as a dangerous health threat, people can be caught off guard as the thermometer creeps higher, on average, each year. In some cases, dangerous heat can arise quickly. In 2021, a young family died of heat stroke on a California trail after setting out for a hike when temperatures were still in the 70s Fahrenheit (low to mid 20s Celsius).

I study health risks in a warming climate as a professor of public health, and I’ve seen heat become a growing concern. Here are some of the key warning signs to watch for when temperatures rise – and ways to keep cool when the heat and humidity get too high.

Signs of heat-related illness to watch for

Heat-related illnesses occur across a spectrum, and mild heat stress can quickly progress to life-threatening heat stroke if a person is exposed to dangerous conditions for too long.

Mild forms of heat-related illness include heat cramps and heat rash, both of which can be caused by extensive sweating during hot conditions. Cooling the body and drinking cool fluids can help.

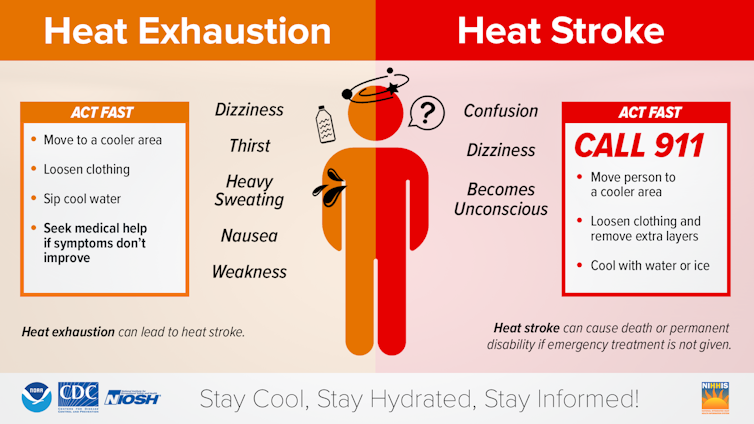

When heat-related illnesses progress into heat exhaustion, the situation is more serious. Heat exhaustion includes symptoms such as dizziness, nausea, excessive sweating, feeling weak, thirst and getting a headache.

Etienne Laurent/AFP via Getty Images

Heat exhaustion is a signal that the body is losing its ability to maintain a stable core temperature. Immediate action such as moving to a cool, ideally air-conditioned space, drinking liquids, loosening clothes and applying wet cloths are some of the recommended steps that can help keep heat exhaustion from progressing to the most dangerous form of heat-related illness, heat stroke.

Heat stroke is a medical emergency. At this point, the body can no longer maintain a stable core temperature. A body with heat stroke can reach 106 degrees Fahrenheit or higher rapidly, and that heat can quickly damage the brain, heart and kidneys.

NOAA/CDC

Typically, someone suffering heat stroke has exhausted their reserves of sweat and salt to stay cool, so sweating eventually stops during heat stroke. Their cognitive ability fails, and they cannot remove themselves from danger. Heat stroke can cause seizures or put someone into a coma as their core temperature rises. If the condition is not treated immediately, and the core temperature continues to rise, heat stroke becomes fatal.

Because heat exhaustion can lead to heat stroke, addressing heat-related illnesses before they progress is vital.

How to tell when the heat is too high

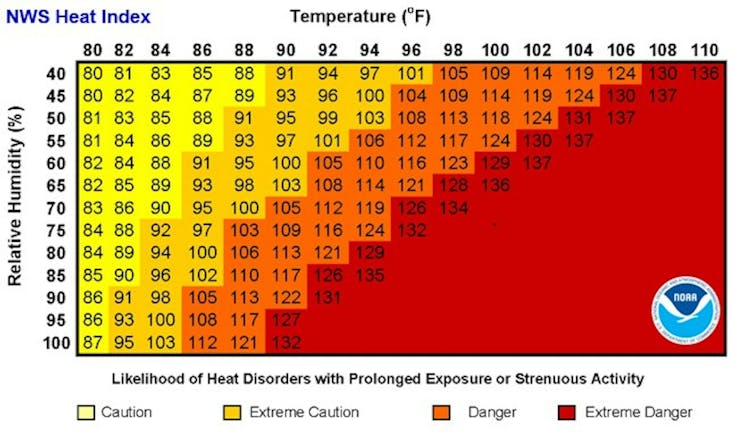

Heat risk isn’t just about temperature – humidity also increases the risk of heat-related illnesses because it affects how well sweating will cool the human body when it gets hot.

Instead of just looking at temperature when planning outdoor activities, check the heat index, which accounts for heat illness risk associated with temperature and relative humidity.

It doesn’t take very high temperatures or very high humidity for the heat index to enter dangerous territory.

NOAA

However, the heat index is still a conservative measure of the impact of heat on humans, particularly for outdoor workers and athletes at summer practices. This is because temperature measurements used in weather forecasting are taken in the shade and are not exposed to direct sunlight. If someone is outside and exposed to the direct sun, the actual heat index can be as much as 15 F higher than the heat index chart indicates.

A more sophisticated measurement of heat effects on human health is what’s known as the wet-bulb globe temperature, which takes into account other variables, such as wind speed and cloud cover. Neither takes into account a person’s physical exertion, which also raises their body temperature, whether working at a construction site or playing soccer.

Tips for staying safe in a heat wave

How can you stay cool when heat waves set in? The answer depends in part on where you are, but the main points are the same:

-

Avoid strenuous outdoor activities in high temperatures if possible. If you start to feel symptoms of heat-related illnesses, drink fluids that will hydrate you. Find shade, rest, and use cool, damp cloths to lower your body temperature. If you see signs of heat stroke in someone else, call for medical help.

-

Be careful with fans. Fans can be useful if the temperature isn’t too high because they wick sweat away from the body and induce evaporative cooling. But at very high temperatures, they can accelerate heat buildup in the body and lead to dangerous conditions. If indoor temperatures reaches 95 degrees or higher, using fans can actually be dangerous and raise the risk of heat-related illnesses.

-

Find a cooling center, library or community center where you can get inside and rest in an air-conditioned space in the hottest hours. In places such as Phoenix, where high temperatures are a regular hazard, cooling centers are typically opened in summer. Northern cities are also opening cooling centers as heat waves occur there more frequently than they did in the past. Urban areas with a lot of pavement and buildings – known as heat islands – can have temperatures well above the city’s average.

-

Hydrate, hydrate, hydrate! Drink plenty of fluids, and don’t forget about the importance of electrolytes. Heat-related dehydration can occur when people sweat excessively, losing water and necessary salts from the body. Some sports drinks or rehydration fluids restore electrolytes and hydration levels.

Older adults and people with disabilities often face higher risks from heat waves, particularly if they can’t easily move to a cooler environment. Communities and neighbors can help protect vulnerable populations by providing cooling centers and bottled water and making regular wellness checks during high heat.

Summer can be a season of fun. Just remember the risks, keep an eye on your friends and neighbors when temperatures rise, and plan ahead so you can beat the heat.

This article, originally published June 19, 2025, has been updated with new heat advisories and forecasts.

![]()

Brian Bossak is not currently receiving relevant external funding for heat-related illness research. In 2017-2019, he served as a consultant on a heat-related research award from the Southeastern Coastal Center for Agricultural Health and

Safety at the University of Florida.

– ref. How to stay safe during heat waves – and heat stroke warning signs to watch for – https://theconversation.com/how-to-stay-safe-during-heat-waves-and-heat-stroke-warning-signs-to-watch-for-257708