Source: The Conversation – France in French (2) – By Gilles Pison, Anthropologue et démographe, professeur au Muséum national d’histoire naturelle et chercheur associé à l’INED, Muséum national d’histoire naturelle (MNHN)

Après le vote il y a 50 ans de la loi Neuwirth autorisant la contraception, la pilule est devenue très vite la première méthode contraceptive en France. Malgré la controverse sur les pilules de nouvelles générations en 2012 qui a entraîné son léger recul, cette méthode reste la plus courante : près d’une Française sur deux ne souhaitant pas être enceinte l’utilise. Est-ce aussi le cas dans les autres pays du monde ? Quelles méthodes sont utilisées ailleurs ?

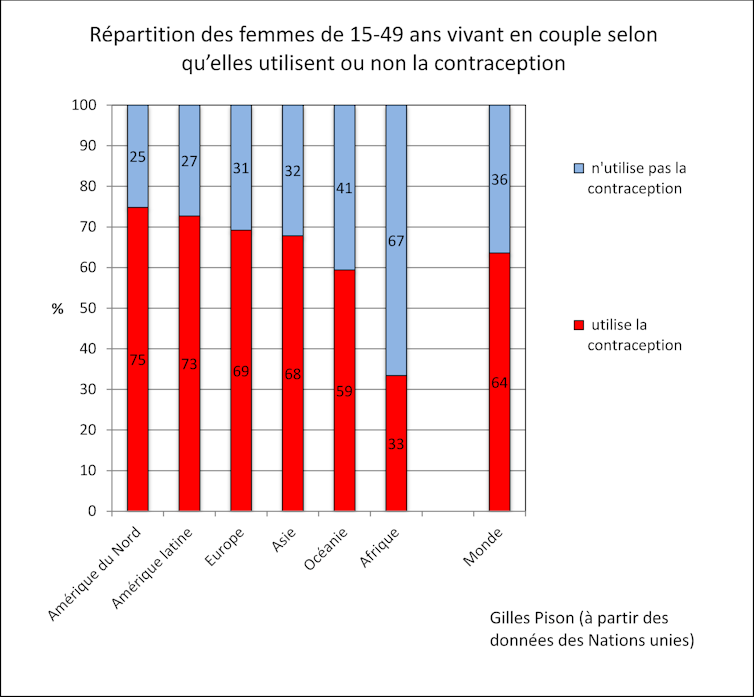

De nos jours, la plupart des couples ont le nombre d’enfants qu’ils veulent et quand ils le veulent. En 2015, près de deux sur trois dans le monde utilisent une méthode de contraception, comme le montre la figure ci-dessous. Le tiers restant soit s’apprête à avoir un enfant – la femme est enceinte – soit souhaite en avoir un prochainement, soit ne le souhaite pas mais ne se protège pas. La contraception est répandue presque partout dans le monde à l’exception de l’Afrique où elle n’est encore utilisée que par un tiers des femmes âgées de 15 à 49 ans mariées ou en union. Elle est beaucoup utilisée en Afrique du Nord et en Afrique australe, mais c’est en Afrique intertropicale qu’elle l’est peu, seulement une femme sur quatre y ayant recours.

Gilles Pison à partir de données ONU, CC BY

Stérilisation : majoritaire dans le monde, mais en baisse

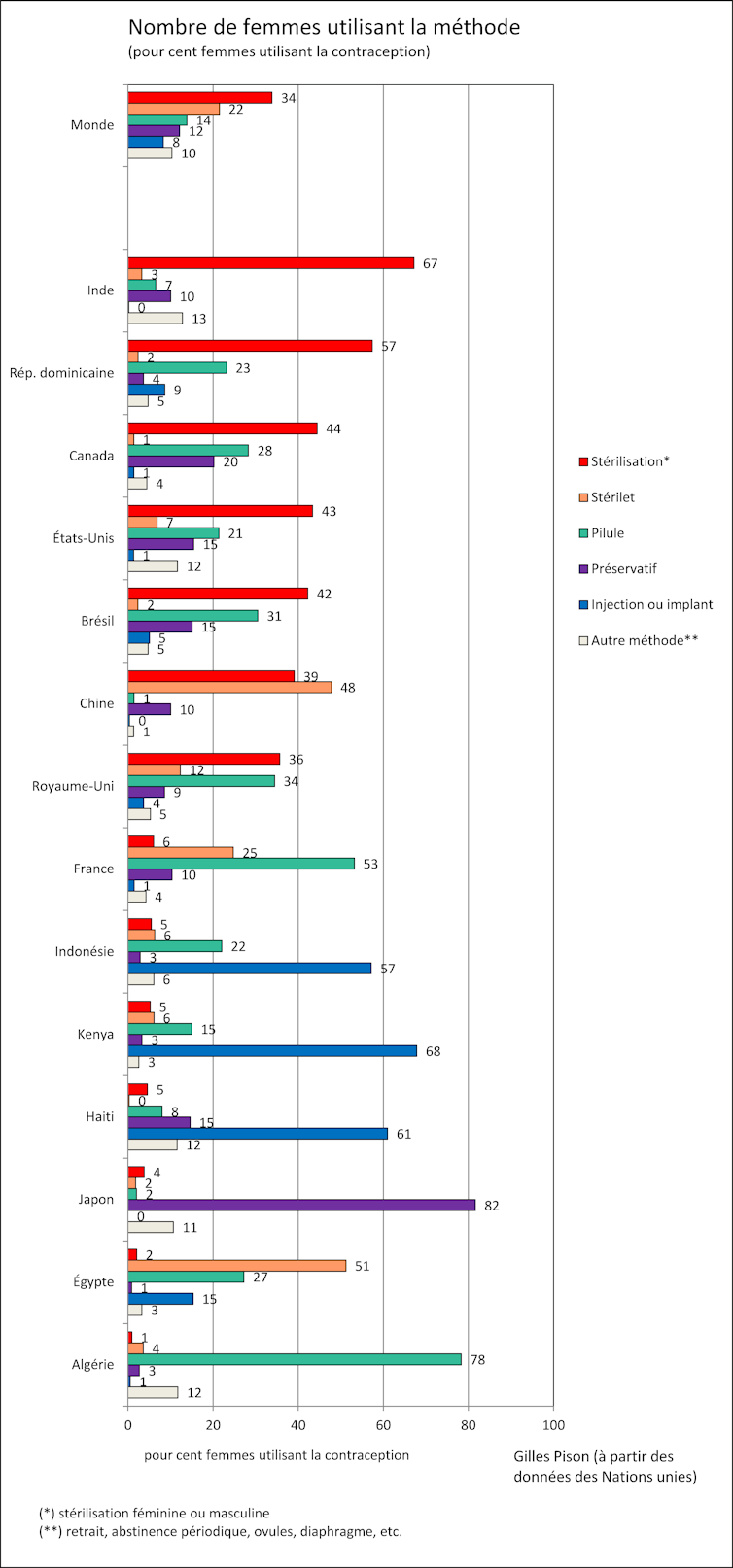

Les méthodes de contraception les plus utilisées dans le monde sont, par ordre d’importance, la stérilisation (dans 34 % des cas), le stérilet (22 %), la pilule contraceptive (14 %), le préservatif (12 %), et l’injection ou l’implant hormonal (8 %). Parmi les autres méthodes moins utilisées, on trouve le retrait et l’abstinence périodique.

La stérilisation a cependant un peu reculé au cours des vingt dernières années, à la fois du côté féminin et masculin – 33 % des femmes ne souhaitant pas être enceintes et se protégeant pour cela avaient recours à la stérilisation féminine en 1994, contre 30 % en 2015. La stérilisation masculine, beaucoup moins fréquente déjà il y a 20 ans, a encore diminué – 8 % de couples en 1994, contre 4 % en 2015. Le recul de la stérilisation s’est fait au profit principalement du préservatif, dont l’usage a été promu pour lutter contre l’épidémie de sida, et des méthodes hormonales, notamment l’injection, utilisée par 2 % des femmes en 1994 et 7 % en 2015. Ces évolutions reflètent pour partie l’évolution de la population d’utilisatrices à l’échelle mondiale, qui compte une part croissante de femmes d’Afrique subsaharienne, la population de cette région étant celle qui a augmenté le plus, et le recours à la contraception y étant à la hausse. Or l’injection hormonale et le préservatif sont des méthodes répandues en Afrique subsaharienne, contrairement à la stérilisation qui est peu pratiquée.

Des modes variables d’un pays à l’autre

D’un pays à l’autre les méthodes de contraception varient beaucoup, comme on peut le voir sur la figure ci-dessous.

Gilles Pison à partir de données ONU, CC BY

En France, la pilule domine, près de la moitié des femmes l’utilisant comme déjà mentionné. Viennent ensuite le stérilet, utilisé par un quart des femmes, puis le préservatif (10 %). La stérilisation ne concerne que 6 % des couples ne souhaitant pas avoir d’enfant – dans un cas sur cinq c’est l’homme qui est stérilisé, dans quatre cas sur cinq, c’est la femme. Les méthodes utilisées en France n’ont guère changé au cours des 20 dernières années mis à part l’importance accrue du préservatif en lien avec l’épidémie de sida, et un léger recul de la pilule au profit des autres méthodes depuis 2012.

En Inde, la stérilisation est la principale méthode de limitation des naissances. Elle est utilisée par les deux tiers des couples qui ne veulent pas d’enfants. La plupart du temps, c’est la femme qui est stérilisée, alors qu’il y a plusieurs dizaines d’années, seule la moitié des couples stérilisés était dans ce cas, l’homme étant stérilisé dans l’autre moitié des cas. La pilule et le stérilet sont très peu utilisés.

En Chine, la stérilisation est très utilisée, comme en Inde. Six fois sur sept, c’est la femme qui est stérilisée, et une fois sur sept, c’est l’homme. Mais les Chinoises utilisent encore plus le stérilet : un sur deux portés dans le monde l’est par une Chinoise. Par contre, elles utilisent très peu la pilule.

Au Brésil, la stérilisation est la première méthode, comme en Inde, et ce sont également les femmes qui sont stérilisées, beaucoup de maris refusant de l’être, comme dans presque tous les pays latins. La deuxième méthode est la pilule contraceptive. Le stérilet est pratiquement inconnu.

Et d’autres méthodes

En Égypte, contrairement à la situation en Inde, en Chine ou au Brésil, la stérilisation est peu fréquente et la principale méthode de contraception est le stérilet. La pilule est également utilisée, ainsi que l’injection. Comprenant des hormones proches de la progestérone, et répétée tous les trois mois, elle a une action analogue à la pilule contraceptive.

En Indonésie, comme en Égypte, la stérilisation est peu fréquente et la pilule relativement diffusée. Mais la méthode la plus fréquente est l’injection, utilisée par la moitié des femmes ne souhaitant pas être enceintes.

En Haïti la situation est similaire à celle de l’Indonésie avec une domination encore plus forte de l’injection : elle est utilisée par deux Haïtiennes ne souhaitant pas être enceintes sur trois.

Au Kenya, les méthodes hormonales autres que la pilule sont également utilisées par les deux tiers des femmes se protégeant, mais elles recourent à l’injection dans seulement deux cas sur trois, choisissant l’implant dans un cas sur trois. Petit bâtonnet implanté sous la peau et remplacé tous les trois ans, il contient des hormones proches de la progestérone qui diffusent de façon lente et continue dans le corps et ont une action analogue à celle de la pilule contraceptive.

En Algérie, presque toute la contraception repose sur la pilule, huit femmes ne souhaitant pas être enceintes sur dix l’utilisant, la plus forte proportion au monde. La proportion est très élevée aussi au Maroc où trois femmes sur quatre l’utilisent.

Au Japon, la méthode de contraception préférée est le préservatif : les Japonais en sont les plus gros consommateurs au monde. En revanche, la pilule n’est pratiquement pas utilisée, et le stérilet non plus. Ils sont considérés comme dangereux.

Cette revue de la situation dans quelques pays illustre combien les usages varient dans le monde en matière de contraception.

Les datavisualisations de cet article ont été réalisées par Marie Simon.

![]()

Gilles Pison ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. La pilule, première méthode de contraception en France, mais pas dans le monde – https://theconversation.com/la-pilule-premiere-methode-de-contraception-en-france-mais-pas-dans-le-monde-89207