Source: The Conversation – (in Spanish) – By Benito Pérez-González, Profesor e Investigador en Marketing y Economía del Deporte, UNIR – Universidad Internacional de La Rioja

Con dos días de diferencia, la revista Forbes y la consultora Football Benchmark publicaron sus rankings de clubes de fútbol más valiosos. Forbes lo publica desde 2011 y el de Football Benchmark celebra en 2025 su décima edición, ya como entidad independiente de la compañía KPMG pero conservando equipo y metodología de trabajo.

Ambos análisis han generado valoraciones diferentes. Aunque parten del hecho común de aplicar un multiplicador a los ingresos, difieren en los elementos que ponderan a ese multiplicador: mientras parece que Forbes da prioridad a la valoración basada en el valor de marca, el impacto comercial y el valor mediático, Football Benchmark tiene un enfoque más fundamental, basado en información contable y financiera.

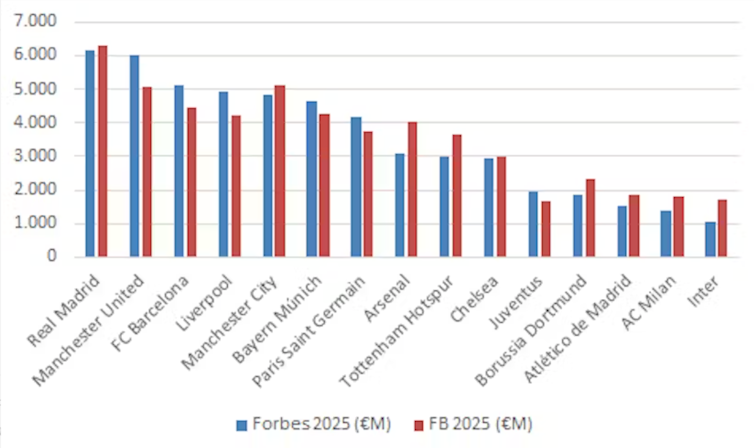

Este artículo se centra en el análisis de las valoraciones de los quince primeros clubes europeos de ambas listas y los compara con sus ingresos (publicados por Deloitte). También analizamos el peso que Forbes otorga al componente marca y buscamos la relación entre el éxito deportivo y la valoración dada a los clubes por ambos modelos.

¿Cómo saber cuánto vale?

Calcular el valor de entidades grandes y complejas sin aplicar modelos rigurosos como el descuento de flujos de caja (que calcula el valor económico de una empresa estimando su capacidad futura de que los ingresos superen a las salidas de efectivo), sin conocer indicadores bursátiles –sólo el Manchester United, el Borussia Dortmund y la Juve cotizan en los mercados– y sin existir muchas operaciones de compraventa recientes que ofrezcan indicios sobre precios, equivale a operar en terreno especulativo.

Por tanto, ambas valoraciones son más simplistas de lo deseable. Además, las metodologías aplicadas no son lo suficientemente transparentes como para poder replicar los cálculos, algo que resulta indispensable en la investigación científica. No obstante, se trata de cifras con amplia difusión mediática y citadas en artículos académicos de finanzas del deporte.

Fuente: elaboración propia a partir de datos de los informes para 2025 de Forbes y Football Benchmarck

Convergencia madridista

Aunque los dos rankings están encabezados por el Real Madrid, hay diferencias notables. Si Forbes da al Arsenal un valor un 30 % menor que Football Benchmark, también valora al Manchester United y a la Juventus un 16 % por encima. En cambio, en el caso del Real Madrid sólo hay un 2 % de diferencia, lo que sugiere una convergencia entre su rendimiento financiero, deportivo y de marca.

En las estimaciones de Forbes es posible identificar patrones. Equipos como Manchester United, FC Barcelona, Bayern Múnich y Liverpool tienen un valor que supone entre 6,1 y 7,8 veces sus ingresos, mientras que los de Borussia Dortmund, AC Milan, Arsenal, Atlético de Madrid e Inter están por debajo, con multiplicadores de ingreso que van de 2,7 a 4,3. Esto podría explicarse por el atractivo global de algunas marcas con grandes expectativas, pero también podría deberse a un sesgo metodológico que privilegia el potencial frente a los datos verificados.

Valor de marca

Los éxitos deportivos recientes no explican por sí solos estas valoraciones. El Manchester City ha sido campeón de la Premier y de Europa, y, aun así, Forbes lo valora menos que al Manchester United, que sigue siendo líder en seguidores en la Commonwealth.

El PSG cae en ambas listas, reflejando quizás la marcha de estrellas como Messi o Mbappé, aunque, paradójicamente, ganaron su primera Champions League al día siguiente de la publicación del informe.

Mientras, el FC Barcelona recibe una valoración significativamente más alta en Forbes –que valora el potencial del nuevo estadio, del equipo y de sus millones de seguidores– que en Football Benchmark, que toma en cuenta, sobre todo, valores contables. Esta divergencia es lógica conociendo los problemas financieros de los culés.

Todo esto apunta a que el valor de un club no depende sólo de sus cuentas ni de sus trofeos. Hay un componente intangible: la percepción. Lo que los demás creen de los equipos.

Una cuestión de método

Los clubes de fútbol europeos han seguido aumentando sus ingresos incluso en contextos económicos adversos. Esto es tenido en cuenta por ambas fuentes, que en sus valoraciones utilizan el análisis fundamental por múltiplos comparables, un método de análisis que busca valorar empresas similares utilizando las mismas métricas financieras.

¿Las diferencias? El enfoque metodológico que aplica Football Benchmarck se acerca más que el de Forbes al de un analista financiero o un fondo institucional. Para estimar el valor de las empresas pondera el multiplicador de ingresos teniendo en cuenta los activos (como la propiedad del estadio), el valor de la plantilla, el número de seguidores en redes sociales o la rentabilidad operativa.

En cambio, Forbes basa su valoración en cada fuente de ingresos: ingresos en el estadio el día de partido (matchday), derechos televisivos, patrocinios y derechos comerciales. Y a todo esto le suma un componente adicional: el valor de marca, que fija entre el 14 y el 18 % del valor total. Forbes pondera principalmente el atractivo global, la visibilidad mediática y el potencial comercial. Como Football Benchmarck, también toma en cuenta el número de seguidores en las redes sociales.

Además, Forbes ajusta sus estimaciones con las operaciones reales de mercado. La última relevante fue en 2024: la familia propietaria del Manchester United, valorado en 6 500 millones de dólares, vendió el 25 % por 1 360 millones. En 2022, el Chelsea fue vendido por 3 200 millones, un valor similar al que le daba Forbes entonces.

¿Valores tangibles o narrativas poderosas?

En la novela El bar de las grandes esperanzas, su joven protagonista se pregunta si estudiar en Harvard o en Yale. A esta disyuntiva le responden entre risas: “Harvard, ¿qué quieres ser? ¿Contable?”.

Después de once años como auditor en una de las Big Four sé bien que los contables, los de Harvard, buscamos valores con base sólida: activos, ingresos, flujos de caja. Más cercanos, aunque con las limitaciones descritas, al enfoque de Football Benchmark. Pero hay también quien valora como los de Yale, de acuerdo a símbolos, prestigio y narrativas poderosas. Ese sería el terreno de Forbes.

A pesar de las limitaciones planteadas, las listas –como las de Forbes, Football Benchmark, Sportico o 2Playbook– resultan valiosas: permiten ordenar el caos, establecer jerarquías y comparar magnitudes que, de otro modo, serían inabarcables.

![]()

Benito Pérez González es socio abonado del Club Atlético de Madrid.

Jose Torres-Pruñonosa es socio del Futbol Club Barcelona.

Raúl Gómez Martínez no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

– ref. Triunfos, seguidores, ingresos… ¿Cómo se calcula el verdadero valor de un equipo de fútbol? – https://theconversation.com/triunfos-seguidores-ingresos-como-se-calcula-el-verdadero-valor-de-un-equipo-de-futbol-258546