Source: The Conversation – UK – By Justin Stebbing, Professor of Biomedical Sciences, Anglia Ruskin University

The NHS is embarking on a trial that could cut prostate cancer diagnosis times from weeks to a single day. The initiative uses artificial intelligence to analyse MRI scans, potentially transforming care for men with the most commonly diagnosed cancer in England.

Up to 15 NHS hospitals, including Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, will pilot the system over the coming months, processing around 10,000 MRI scans. If successful, it could be rolled out nationally – though questions remain about accuracy, costs and whether faster diagnosis always means better outcomes.

The trial represents the NHS’s latest attempt to address both the emotional toll of prolonged uncertainty and the practical problem of late diagnoses that have long characterised prostate cancer care. For many men, the wait between initial suspicion and confirmed diagnosis is marked by weeks of anxiety, often while the disease progresses unchecked.

Currently, men suspected of having prostate cancer face a lengthy process. After a GP referral, it can take days or weeks to get an MRI scan, have it interpreted by a radiologist and undergo a follow-up biopsy if needed. A national shortage of radiologists has created significant bottlenecks, with some men waiting over a month for results.

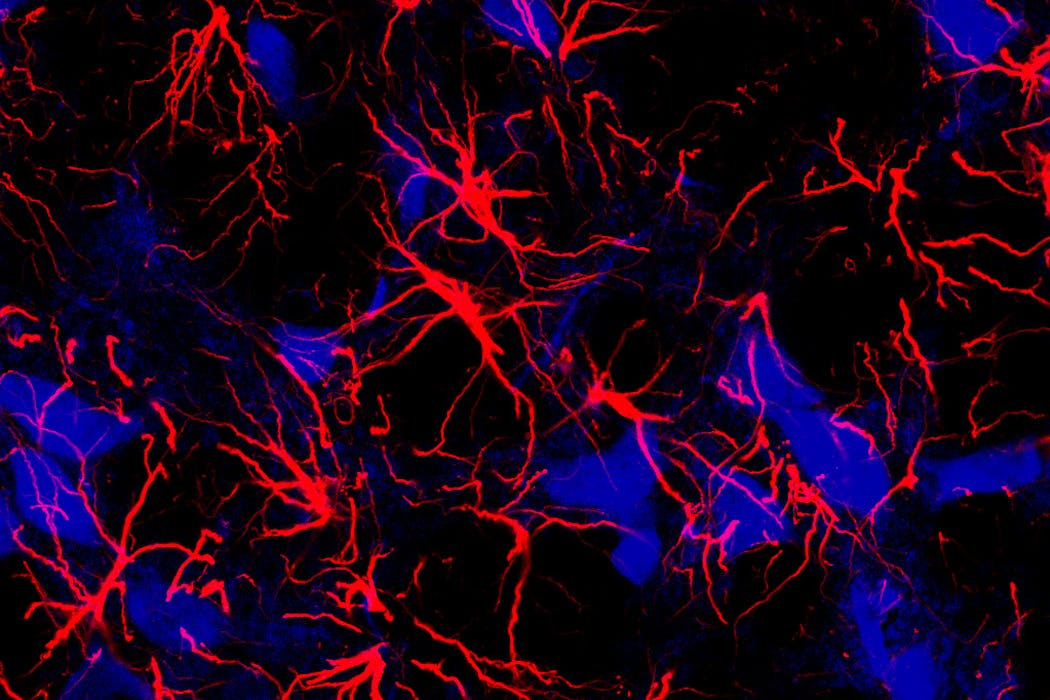

The AI system changes this timeline. Once a man has had his MRI scan, the software analyses the images in minutes. Building on major researchstudies, it identifies abnormal areas and generates a probability score, mapping the exact location of suspicious lesions in the prostate.

When the software flags a scan as high-risk, it is immediately prioritised for review by a human radiologist, and the patient can be booked for a biopsy the same day. For lower-risk scans, men could receive reassuring news almost immediately rather than enduring weeks of anxious waiting.

The system aims to deliver what clinicians describe as accuracy and speed that rivals traditional methods. In some settings, AI analysis has matched or exceeded human radiologist performance, though real-world implementation will test whether laboratory results translate to busy NHS hospitals.

Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock.com

The case for speed

Prostate cancer is now the most commonly diagnosed cancer among men in England, with about one in eight men expected to be affected in their lifetime. The number of diagnoses has risen steadily, and too many men are still diagnosed when the disease is already advanced, making survival less likely and treatment more challenging.

Reducing diagnostic delay could save lives, though diagnosing some cancers earlier isn’t always better. Some slow-growing prostate cancers may never cause symptoms or shorten life, and early detection can lead to unnecessary treatment and its associated side effects. The challenge is distinguishing aggressive cancers that need urgent intervention from those that can be safely monitored.

There is also troubling variability in cancer diagnosis across the UK, with significant differences in waiting times and outcomes depending on where a patient lives. By making specialist analysis instantly available regardless of whether a hospital has a subspecialist radiologist on hand, every man, regardless of location, could theoretically benefit from the same standard of diagnostic assessment.

The system also promises to ease pressure on NHS teams. By handling initial MRI interpretation, the AI frees up radiologist time to focus on complex or urgent cases. This matters particularly given workforce pressures – the NHS has struggled to recruit and retain enough radiologists to meet growing demand.

As the NHS seeks to do more with strained resources, AI-driven tools have the potential to save time and money.

The AI won’t work alone

The technology is designed to work alongside clinicians rather than replace them. AI acts as a “second reader”, complementing radiologist expertise to ensure nothing is missed. The aim is faster and more reliable decisions – sparing men unnecessary biopsies for benign conditions while swiftly directing those with troubling signs to the right care.

This partnership approach is considered crucial. Although AI can process vast amounts of imaging data rapidly, human judgment remains essential for interpreting results in the context of each patient’s individual circumstances, medical history and symptoms. The technology is not intended to make final diagnostic decisions, but to augment clinical decision-making.

Recent research suggests that most men would welcome the invitation to take part in a national screening programme, countering assumptions about reluctance to engage with health checks. As confidence grows in AI-powered diagnostics, this could encourage more men to come forward for testing, potentially catching cancers earlier in those most at risk.

Whether the pilot delivers on its promise of reducing the time from referral to diagnosis – and whether speed translates to better outcomes – will become clearer over the coming months. The results will be closely watched by other health services considering similar approaches.

![]()

Justin Stebbing does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. NHS trials AI tool for faster prostate cancer diagnosis – https://theconversation.com/nhs-trials-ai-tool-for-faster-prostate-cancer-diagnosis-268932