Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Jean-Nicolas Bordeleau, Research Fellow, Jeff Bleich Centre for Democracy and Disruptive Technologies, Flinders University

Conspiracy theories are a widespread occurrence in today’s hyper connected and polarised world.

Events such as Brexit, the 2016 and 2020 United States presidential elections, and the COVID pandemic serve as potent reminders of how easily these narratives can infiltrate public discourse.

The consequences for society are significant, given a devotion to conspiracy theories can undermine key democratic norms and weaken citizens’ trust in critical institutions. As we know from the January 6 riot at the US Capitol, it can also motivate political violence.

But who is most likely to believe these conspiracies?

My new study with Daniel Stockemer of the University of Ottawa provides a clear and perhaps surprising answer. Published in Political Psychology, our research shows age is one of the most significant predictors of conspiracy beliefs, but not in the way many might assume.

People under 35 are consistently more likely to endorse conspiratorial ideas.

This conclusion is built on a solid foundation of evidence. First, we conducted a meta analysis, a “study of studies”, which synthesised the results of 191 peer-reviewed articles published between 2014 and 2024.

This massive dataset, which included over 374,000 participants, revealed a robust association between young age and belief in conspiracies.

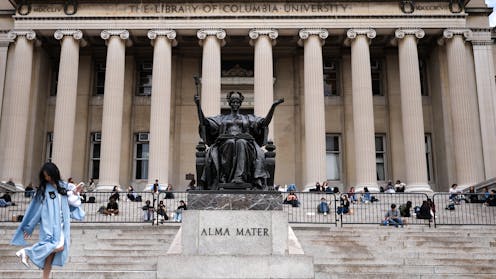

To confirm this, we ran our own original multinational survey of more than 6,000 people across six diverse countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada, Germany, the US and South Africa.

The results were the same. In fact, age proved to be a more powerful predictor of conspiracy beliefs than any other demographic factor we measured, including a person’s gender, income, or level of education.

Why are young people more conspiratorial?

Having established conspiracy beliefs are more prevalent among younger people, we set out to understand why.

Our project tested several potential factors and found three key reasons why younger generations are more susceptible to conspiracy theories.

1. Political alienation

One of the most powerful drivers we identified is a deep sense of political disaffection among young people.

A majority of young people feel alienated from political systems run by politicians who are two or three generations older than them.

This under representation can lead to frustration and the feeling democracy isn’t working for them. In this context, conspiracy theories provide a simple, compelling explanation for this disconnect: the system isn’t just failing, it’s being secretly controlled and manipulated by nefarious actors.

2. Activist style of participation

The way young people choose to take part in politics also plays a significant role.

While they may be less likely to engage in traditional practices such as voting, they are often highly engaged in unconventional forms of participation, such as protests, boycotts and online campaigns.

These activist environments, particularly online, can become fertile ground for conspiracy theories to germinate and spread. They often rely on similar “us versus them” narratives that pit a “righteous” in-group against a “corrupt” establishment.

3. Low self-esteem

Finally, our research confirmed a crucial psychological link to self-esteem.

For individuals with lower perceptions of self worth, believing in a conspiracy theory – blaming external, hidden forces for their problems – can be a way of coping with feelings of powerlessness.

This is particularly relevant for young people. Research has long shown self esteem tends to be lower in youth, before steadily increasing with age.

What can be done?

Understanding these root causes is essential because it shows simply debunking false claims is not a sufficient solution.

To truly address the rise of conspiracy theories and limit their consequences, we must tackle the underlying issues that make these narratives so appealing in the first place.

Given the role played by political alienation, a critical step forward is to make our democracies more representative. This is best illustrated by the recent election of Labor Senator Charlotte Walker, who is barely 21.

By actively working to increase the presence of young people in our political institutions, we can help give them faith that the system can work for them, reducing the appeal of theories which claim it is hopelessly corrupt.

More inclusive democracy

This does not mean discouraging the passion of youth activism. Rather, it is about empowering young people with the tools to navigate today’s complex information landscape.

Promoting robust media and digital literacy education could help individuals critically evaluate the information they encounter in all circles, including online activist spaces.

The link to self-esteem also points to a broader societal responsibility.

By investing in the mental health and wellbeing of young people, we can help boost the psychological resilience and sense of agency that makes them less vulnerable to the simplistic blame games offered by conspiracy theories.

Ultimately, building a society that is resistant to misinformation is not about finding fault with a particular generation.

It is about creating a stronger, more inclusive democracy where all citizens, especially the young, feel represented, empowered, and secure.

![]()

Jean-Nicolas Bordeleau receives funding from Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

– ref. 3 reasons young people are more likely to believe conspiracy theories – and how we can help them discover the truth – https://theconversation.com/3-reasons-young-people-are-more-likely-to-believe-conspiracy-theories-and-how-we-can-help-them-discover-the-truth-261074