Source: The Conversation – in French – By Éric Le Fur, Professeur, INSEEC Grande École

Derrière le glamour des courses hippiques se joue un marché mondial des chevaux de course évalué à 300 milliards de dollars (ou 259,2 milliards d’euros). Véritables actifs vivants, les pur-sang attirent investisseurs et passionnés dans un univers où performances sportives, pedigree et spéculation s’entremêlent. Mais entre prestige et rentabilité, le rapport rendement/risque reste souvent défavorable.

Le monde des courses de chevaux n’est pas seulement un sport, c’est un écosystème économique et culturel, où un actif unique, le cheval de course, concentre enjeux financiers, prestige et tradition. Comprendre ce marché, c’est plonger dans un univers où la performance sportive rencontre l’investissement et la passion. Notre contribution questionne ainsi le risque et le rendement de cet investissement.

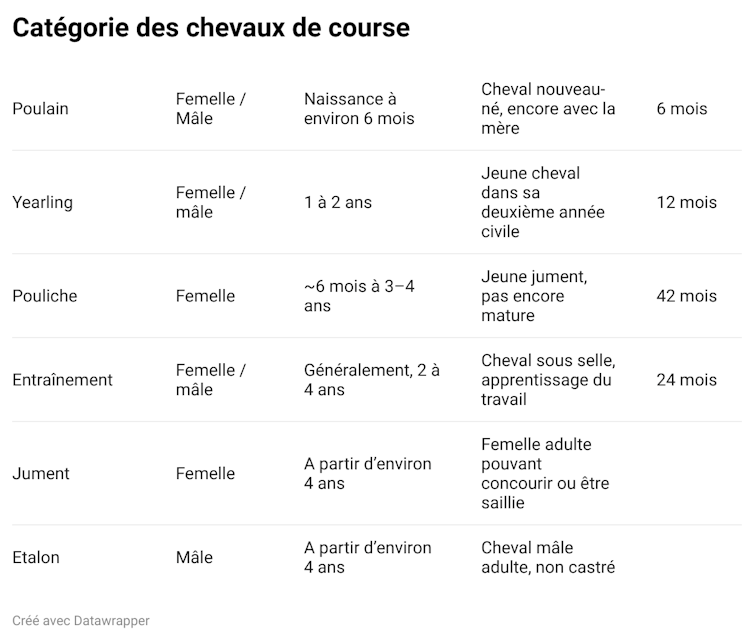

Définition et catégories d’un cheval de course

C’est un équidé élevé, dressé et entraîné spécifiquement pour participer à des compétitions officielles de vitesse ou d’endurance. Il ne faut pas le confondre avec un cheval de sport qui est utilisé dans d’autres disciplines équestres, comme le saut d’obstacles, le dressage ou le concours complet. Sa valeur dépend à la fois de sa performance sportive, de sa lignée génétique et de son potentiel de reproduction. Les chevaux de course sont classifiés en fonction de leur âge.

Fourni par l’auteur

Marché des chevaux de course et ventes aux enchères

Contrairement à un actif financier, un cheval est un actif vivant qui peut courir, gagner des compétitions, générer des revenus, participer à la reproduction et être vendu. C’est un marché où la performance sportive et la valeur économique sont fortement liées. Ce marché, mondial, est évalué à 300 milliards de dollars (259,2 milliards d’euros).

La France, le Royaume-Uni et l’Irlande représentent 133 milliards de dollars (114,9 milliards d’euros). Les États-Unis et le Canada totalisent 118 milliards de dollars (101,9 milliards d’euros). Le reste des ventes se répartit entre l’Asie-Océanie (Australie, Chine, Hong-kong et Japon), l’Afrique du Sud, et le Moyen-Orient (Arabie saoudite et les Émirats arabes unis).

ErinDaugherty/Shutterstock

L’événement phare en France est la vente de yearlings d’août aux enchères de Deauville (Calvados), organisée par Arqana, des pur-sang dans leur deuxième année. Depuis plusieurs années, les records dans les ventes aux enchères s’accumulent. Par exemple, le 9 décembre 2023, lors de la vente d’élevage de Deauville, Place-du-Carrousel, une jument de 4 ans a été adjugée 4,025 millions d’euros. Lors de la même vente en 2022, Malavath, une pouliche d’entraînement, a été adjugée 3,2 millions d’euros. Enfin, une pouliche de Dubawi, acquise en 2015 pour 2,6 millions d’euros par Godolphin, l’écurie du cheikh Mohammed Al-Maktoum, émir de Dubaï, détient le record pour un yearling vendu aux enchères publiques en France.

Construction d’un indice de prix pour déterminer le risque et le rendement

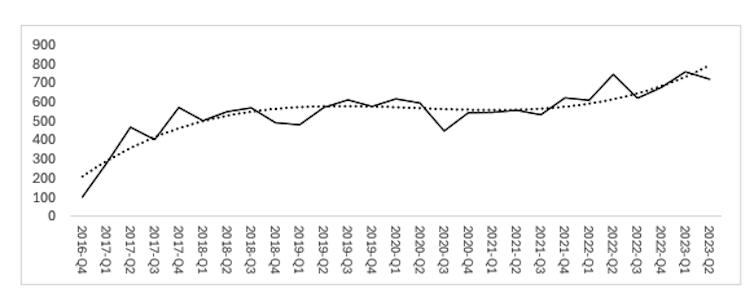

Nous utilisons 28 310 ventes aux enchères provenant du site Arqana entre novembre 2016 et novembre 2023. Avec 12 097 ventes, les yearlings sont majoritaires, suivis des juments (4 951 ventes) et des chevaux d’entraînement (3 417 ventes).

Plus de 93 % des ventes sont réalisées à Deauville ; le reste, 1 054 à Saint-Cloud (Hauts-de-Seine), 553 en ligne, 87 à Chantilly (Oise) et 29 à Auteuil (Paris XVIᵉ). Les amateurs représentent 22 % des acheteurs. La difficulté de l’analyse repose sur le fait que chaque cheval possède des caractéristiques uniques (généalogie, pays d’origine, sexe, âge). Afin d’extraire une tendance des prix qui mesure l’évolution de la valeur globale des chevaux de course en prenant en compte leurs attributs spécifiques, nous construisons un indice de prix hédonique.

Fourni par l’auteur

La tendance générale est à la hausse, avec une accélération des prix après la pandémie de Covid-19. Cependant, l’analyse des indices par catégorie révèle des évolutions de prix très différentes. Alors que les chevaux de deux ans, les chevaux d’entraînement et les juments ont connu des tendances stables, voire en baisse, après la pandémie de Covid-19, les yearlings et les pouliches ont atteint des sommets.

Rendements et risques d’un investissement dans les chevaux de course

Nos résultats indiquent des rendements positifs mais faibles. Tous les rendements trimestriels et semestriels sont positifs, suggérant qu’investir dans les chevaux de course pourrait être une opportunité, mais sont généralement inférieurs au taux sans risque.

Par conséquent, investir dans les chevaux de course semble davantage relever de la passion que de la rentabilité financière. Par catégorie, les yearlings sont les plus attractifs pour les investisseurs prêts à prendre des risques, surtout depuis la pandémie de Covid-19.

Autres caractéristiques des chevaux à prendre en compte pour mieux appréhender les rendements

Certaines informations ne sont pas prises en compte dans notre modèle et permettraient probablement d’affiner les résultats. La valeur d’un cheval de course dépend aussi de ses caractéristiques physique, morale et esthétique. Un corps bien proportionné, un cœur puissant, un métabolisme efficace et une récupération rapide sont des éléments clés de la performance et de la longévité. Le tempérament du cheval joue également un rôle crucial. La couleur de la robe, bien qu’elle n’ait aucune influence sur les aptitudes physiques, peut susciter l’attrait commercial. Enfin, dans certaines catégories, les informations sur les performances passées peuvent peser significativement sur le prix.

Compte tenu de ces facteurs, le retour sur investissement des chevaux de course est une équation complexe. Il dépend de la différence entre les prix de revente et d’achat, ou des bénéfices actualisés, incluant le prix de revente. Supposons que l’investissement consiste à acheter un cheval de sa conception à sa mort. Dans ce cas, la valeur actuelle nette prend en compte négativement les prix actualisés de la saillie, de l’élevage, de l’entraînement, du transport et de l’entretien post-carrière, et positivement les bénéfices actualisés des courses et de l’élevage. Il est également nécessaire de prendre en compte les risques de blessure, de maladie et de sous-performance potentielle.

Les chevaux de course représentent-ils davantage un investissement de prestige ou de passion ?

Comme nous le démontrons, les chances de profit sont faibles, et il peut être plus facile de considérer cet investissement comme une dépense récréative. Investir dans un cheval de course peut être émotionnellement gratifiant. Pour les passionnés, le prestige et la passion justifient les pertes.

Posséder un cheval de course pour les élites et la communauté équestre, surtout s’il remporte des courses prestigieuses, est synonyme de reconnaissance. Ainsi, certains investisseurs sont davantage motivés par l’amour des chevaux, la passion des sports équestres et l’excitation des courses que par la rentabilité financière. Il s’agit d’un loisir coûteux, comme les voitures de collection.

![]()

Les auteurs ne travaillent pas, ne conseillent pas, ne possèdent pas de parts, ne reçoivent pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’ont déclaré aucune autre affiliation que leur organisme de recherche.

– ref. Le marché des chevaux de course : entre passion, économie et patrimoine vivant – https://theconversation.com/le-marche-des-chevaux-de-course-entre-passion-economie-et-patrimoine-vivant-265991