Source: The Conversation – USA – By Ray Brescia, Associate Dean for Research and Intellectual Life, Albany Law School

As the United States edges up to the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence in 2026, one of the core principles the founders sought to advance – that the government must act with accountability and in accordance with the rule of law – is being strongly tested.

In their deliberations leading up to the declaration, the founders would not just raise deep concerns that the government of King George III was violating the Colonists’ rights, which they described in the declaration. They would also enshrine these principles in the U.S. Constitution over a decade later through the concept of “due process.”

What did the framers likely mean when they did so? That’s no longer simply an academic question for legal scholars like me. The meaning and application of due process has become a crucial issue in the U.S., most often with respect to the Trump administration’s migrant deportation efforts.

Over the past several months, the U.S. Supreme Court has made several rulings in deportation-related cases with respect to what’s called the due process clause of the Constitution.

In April 2025, in the case Trump v. J.G.G., the court seemed to state quite clearly that deportations could not take place without due process. More recently, however, in D.H.S. v. D.V.D., the Supreme Court prevented a lower court from providing due process protections to a group of men the administration wanted to deport to South Sudan, where they are at risk of facing torture and even death.

These seemingly contradictory rulings not only make it unclear when due process applies but probably leave many asking what the term “due process of law” even means and how it works.

Mike Kline, Moment/Getty Images

The origins of due process

The American concept of due process can be traced from medieval England to its modern formulation by the U.S. Supreme Court. Doing so allows the meaning of due process to come into focus. It also calls into question the court’s most recent ruling on this issue.

The concepts of due process and the rule of law largely emerged in the 13th century in the Magna Carta, a formal, written agreement between King John of England and the rebel aristocracy that effectively established legal constraints on government.

One key passage from the Magna Carta provided that “No Freeman shall be taken, or any otherwise imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or destroyed; nor we will not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful Judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land.”

This accord established formal constraints on a previously unrestrained regent, setting English law on the course that would prioritize rule of law over the whims of the monarch.

Over a century later, Parliament would pass the English statute of 1354 that said “That no Man of what Estate or Condition that he be, shall he put out of Land or Tenement, nor taken nor imprisoned, nor disinherited, nor put to death, without being brought in Answer by due Process of the Law.”

These principlesd evolve over time in British law and then informed the emerging revolutionary spirit in the American Colonies.

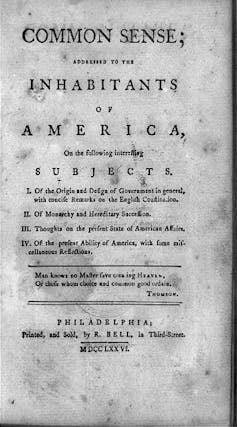

Released in January 1776, Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense would help galvanize and steel many Colonists for the revolutionary conflict to come. The work shifted the focus of Colonists’ anger from trying to force the king to treat them better to more radical change: independence and a country governed by the rule of law.

Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division

What the Colonists wanted, Paine wrote, was not a monarch: “So far as we approve of monarchy, that in America THE LAW IS KING. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other.”

Defining due process

After independence, many of the original 13 states adopted their own constitutions that would enshrine principles akin to due process to protect their constituents from government overreach, such as that government was to be bound, as it was in Virginia’s Declaration of Rights in 1776, by “the law of the land.”

But it was not until the nation adopted the Bill of Rights – the first 10 amendments to the Constitution – in 1791 that the federal government could not act in a way that deprived the populace of life, liberty or property without due process of law. After the Civil War, the 14th Amendment would apply these same protections to all government action, state and federal.

The contemporary and most comprehensive formulation of what due process requires can be found in the Supreme Court’s ruling in the 1970 case Goldberg v. Kelly, brought by welfare recipients challenging their loss of such benefits without a hearing.

In that case, the court determined that when governments attempt to deprive someone of their life, liberty or property, the target of those attempts must receive fair notice of the charges or claims against them that would justify that loss; be given an opportunity to defend against those claims; and possess the right to have such defenses considered by an impartial adjudicator.

The Supreme Court in 1976 would accept that due process protections in different settings will vary based on a number of variables. Those include what is at stake in the case, the likelihood that government might make a mistake in a particular setting, and the benefits and burdens of providing certain forms of process in a given situation.

When someone’s life is literally on the line, for example, more exacting procedures are required. At the same time, regardless of how important the interest that is subject to due process – whether it is one’s life, one’s home, one’s liberty, or something else – the components of fair notice, an opportunity to be heard, and to have one’s case decided by an impartial adjudicator must be meaningful.

As the court said in Mullane vs. Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co. in 1950: “Process which is a mere gesture is not due process.”

![]()

Ray Brescia does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Due process: What it means in US law and its implications for migrant rights – https://theconversation.com/due-process-what-it-means-in-us-law-and-its-implications-for-migrant-rights-259756