Source: The Conversation – in French – By Christian Abadioko Sambou, Dr en Sciences Politiques, spécialiste en paix & sécurité, Université Numérique Cheikh Hamidou Kane

Depuis plus de dix ans, les violences terroristes déstabilisent le Sahel central (Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger), fragilisant les sociétés, les institutions et les régimes démocratiques. Dans ce contexte, des coups d’État militaires ont eu lieu au Mali (2020, 2021), au Burkina Faso (2022) et au Niger (2023), invoquant la nécessité de restaurer l’ordre. Ces régimes prolongent la transition au-delà de son cadre temporaire, privilégiant la promesse de stabilité à un retour constitutionnel.

En tant que chercheur, j’ai étudié les crises sécuritaires en Afrique de l’Ouest, notamment les conflits sécessionnistes et leur évolution dans des Etats en permanente modernisation et démocratisation. Selon moi, la trajectoire des institutions et des régimes politiques, ainsi que leur effet sur la paix et la sécurité au Sahel, constitue un sujet de recherche particulièrement pertinent.

Dans cet article, j’explore comment l’insécurité persistante légitime les gouvernements militaires, où le pouvoir repose sur la gestion de la menace plutôt que sur l’élection, transformant ainsi la transition en un mode de gouvernance durable.

Echec de dix ans de lutte contre le terrorisme

Les transitions militaires au Sahel central sont le symptôme d’un échec plus large : celui des politiques internationales de lutte contre le terrorisme. Depuis 2013, l’engagement militaire étranger — à travers l’opération Serval puis Barkhane, la force conjointe du G5 Sahel, ainsi que divers dispositifs bilatéraux et multilatéraux soutenus par l’Union européenne — a privilégié une approche strictement sécuritaire. Cette stratégie a eu pour effet de marginaliser des dimensions essentielles telles que la gouvernance démocratique, la justice sociale et le développement.

La coordination entre les multiples acteurs internationaux et locaux a manqué de cohérence, chacun poursuivant des agendas parfois divergents. Cette fragmentation stratégique a favorisé l’extension des violences : du nord du Mali vers le centre, puis dans l’ensemble du Burkina Faso et certaines régions du Niger comme Tillabéry, Tahoua ou Diffa.

Les données d’Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED, une organisation qui recueille des données sur les conflits violents et les manifestations) montrent une nette augmentation des violences et des morts après 2020, principalement au Burkina Faso épicentre du terrorisme. Le nombre de décès lié aux violences a augmenté de 28 % entre 2020 et 2022 (année du coup d’Etat). Depuis 2020, le pays a enregistré plus de 28 000 décès (20 000 au Mali,7 000 au Niger).

Les conséquences humanitaires sont alarmantes : des milliers de morts au Sahel central, la fermeture de près de 10 000 écoles et centres de santé (OCHA), et près de 3 millions de personnes déplacées selon le Haut commissariat des unies pour les réfugiés (UNHCR).

Dans ce chaos, les groupes armés prolifèrent. Ils ont de plus en plus recours à l’utilisation de drones. Le Groupe de soutien à l’islam et aux musulmans (GSIM), l’État islamique au grand Sahara (EIGS), Boko Haram (au Nigeria), la Katiba Macina (au Mali), ainsi que des milices d’autodéfense et des groupes communautaires armés, contribuent à aggraver les tensions locales.

La perte de légitimité des gouvernements civils et la défiance envers les partenaires internationaux se sont accentuées. Cela s’est traduit par un rejet massif de la présence militaire étrangère et une contestation croissante des élites locales. Des manifestations ont éclaté à Bamako (2020), Ouagadougou (2021) et Niamey (2023). La confiance envers la MINUSMA, Barkhane et la Mission de formation de l’Union européenne au Mali (EUTM) s’est progressivement effritée.

Dans ce contexte, les transitions militaires apparaissent pour certains citoyens de ces pays comme une réponse à l’échec des interventions extérieures. Les militaires sont perçus comme les seuls capables d’agir dans un environnement dominé par l’urgence sécuritaire. Or, cette réponse ne règle ni les causes profondes ni les effets délétères du conflit.

Coups d’Etat militaires et « solutions transitoires »

Depuis 2020, les coups d’État militaires au Sahel central se multiplient, directement liés à la persistance d’une crise sécuritaire profonde. Le Mali a ainsi connu deux coups en août 2020 et mai 2021, suivi du Burkina Faso en janvier et septembre 2022, puis du Niger en juillet 2023.

Si les premiers coups d’Etat des années 60 à 80 ont souvent été attribués aux influences étrangères, la vague de coups d’État récente depuis 2020 au Sahel central, résulte en réalité davantage d’une grave détérioration sécuritaire interne que d’une manipulation extérieure. Mais désormais, les dirigeants utilisent une rhétorique sécuritaire prévalente depuis les années 2000 pour légitimer leurs actions politiques et judiciaires, réduisant ainsi tout débat politique au seul prisme sécuritaire.

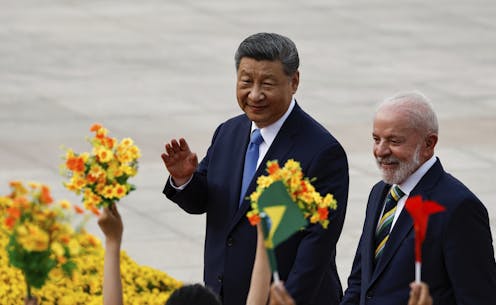

Face à l’échec sécuritaire des États, les régimes militaires du Sahel central ont adopté une stratégie de durcissement, s’alliant à des acteurs comme la Russie et les paramilitaires d’Africa Corps (ex-Wagner). Rejetant les approches multilatérales de la Minusma, de la Communauté économique des Etats de l’Afrique de l’ouest (Cedeao) ou de la France, ces régimes revendiquent leur souveraineté et bouleversent la géopolitique régionale. Pourtant, les transitions se prolongent sans freiner les violences : les attaques terroristes se poursuivent, les groupes armés restent actifs.

Pire, cette réponse strictement militaire engendre des violations des droits humains, aggrave les tensions communautaires et favorise la radicalisation.

Ainsi, loin d’apporter une véritable stabilisation, les transitions deviennent progressivement des outils de répression politique, de restriction des libertés individuelles et de musèlement des contre-pouvoirs, notamment au Mali.

Finalement, la combinaison complexe entre instabilité politique et sécuritaire entretient ce cycle continu de transitions prolongées. Cela révèle les limites intrinsèques de ces transitions lorsqu’elles sont envisagées comme seule réponse à la crise durable du Sahel central.

Des assises nationales plutôt que des élections

La notion de transition, entendue comme une période brève entre deux régimes politiques, tend à perdre son sens au Sahel central. Traditionnellement, une transition comprend deux sous-phases : la libéralisation (ouverture politique) et l’organisation d’élections libres menant à un régime démocratique. Toutefois, au Mali, au Burkina Faso et au Niger, les autorités militaires prolongent cette phase au point de consolider un nouveau pouvoir qui se veut permanent, et rompt avec la tradition de démocratisation.

Les assises nationales, censées être inclusives, sont devenues un outil de légitimation du pouvoir militaire au détriment des élections. Ces assises, tenues au Mali (septembre 2020, décembre 2021, juin 2023), au Burkina Faso (février 2022, octobre 2022, mai 2024) et au Niger (concertations limitées et non nationales), se présentent comme des assemblées populaires, mais elles contournent les mécanismes démocratiques en excluant les voix divergentes et en opérant sur la base d’un consensus préétabli favorable aux militaires.

Elles se substituent à l’élection en définissant la durée de la transition, en érigeant des colonels en généraux, en nommant des présidents de la République, et en fixant les orientations économiques du pays. Ces pratiques traduisent une institutionnalisation de la gouvernance militaire, éloignée du caractère temporaire d’une transition.

Parallèlement, les régimes militaires jouissent d’un soutien populaire alimenté par un rejet massif de la France, de la communauté économique des Etas de l’Afrique de l’ouest (Cedeao) et des élites politiques traditionnelles. La perception d’un manque de compassion et de solidarité dans la lutte contre le terrorisme, les sanctions imposées par les institutions régionales suite aux coups d’Etat, perçues comme des relais des puissances occidentales, ont légitimé aux yeux des opinions locales un retrait des trois Etats de la Cedeao.

Ce contexte a contribué à la création de l’Alliance des États du Sahel (AES), structure à vocation sécuritaire mais de plus en plus politique. L’AES cherche à structurer un nouvel ordre régional en bousculant les équilibres régionaux.

Recul de la démocratie

Le discours souverainiste, profondément anti-occidental, s’appuie à la fois sur le passif colonial et l’échec sécuritaire des partenaires classiques. Il a permis de matérialiser le départ de la France de la région, sans pour autant construire une véritable autonomie stratégique. Le remplacement de la force Barkhane par Wagner, devenu Africa Corps, interpelle toutefois sur la souveraineté revendiquée.

La gouvernance militaire repose désormais sur un agenda sécuritaire renforcé, où les élections sont repoussées sine die, les libertés restreintes et les droits humains souvent bafoués. Tout cela justifié par l’état de guerre contre le terrorisme. Cette militarisation se manifeste aussi par l’intégration des civils dans des gouvernements militaires et la mobilisation de forces paramilitaires comme les Volontaires pour la défense de la patrie (VDP) au Burkina Faso.

Face à cette dynamique, la démocratie électorale recule tandis que d’autres pays ouest-africains (Sénégal, Cap-Vert, Bénin) conservent une trajectoire démocratique. Le contraste souligne les défis historique de sécurité et de stabilité politique communs à l’ensemble des pays de la région. Il soulève surtout la question de l’évolution des régimes politiques en situation de conflits asymétriques.

Au Sahel central, on assiste ainsi à une réinvention du logiciel de lecture des régimes de transition.

![]()

Christian Abadioko Sambou does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Afrique de l’Ouest : comment les transitions militaires se nourrissent des dynamiques sécuritaires – https://theconversation.com/afrique-de-louest-comment-les-transitions-militaires-se-nourrissent-des-dynamiques-securitaires-262056