Source: The Conversation – UK – By Veronika Hinman, Deputy Director, Portsmouth Military Education Team, University of Portsmouth

The EU is considering a range of options as it tries to work out how to continue to fund Ukraine’s defence against Russia. There are three mechanisms presently under consideration. One is using Russia’s frozen assets to back a loan of €140 billion (£124 billion). Another is borrowing the money at interest, although this is not popular.

The third idea, which was proposed by Norwegian economists, is that Norway could use its €1.8 trillion sovereign wealth fund – the biggest in the world – to guarantee the loan. Their reasoning was that Norway, Europe’s biggest producer of oil and gas, has made an extra €109 billion from the rise in gas prices after Russia’s invasion.

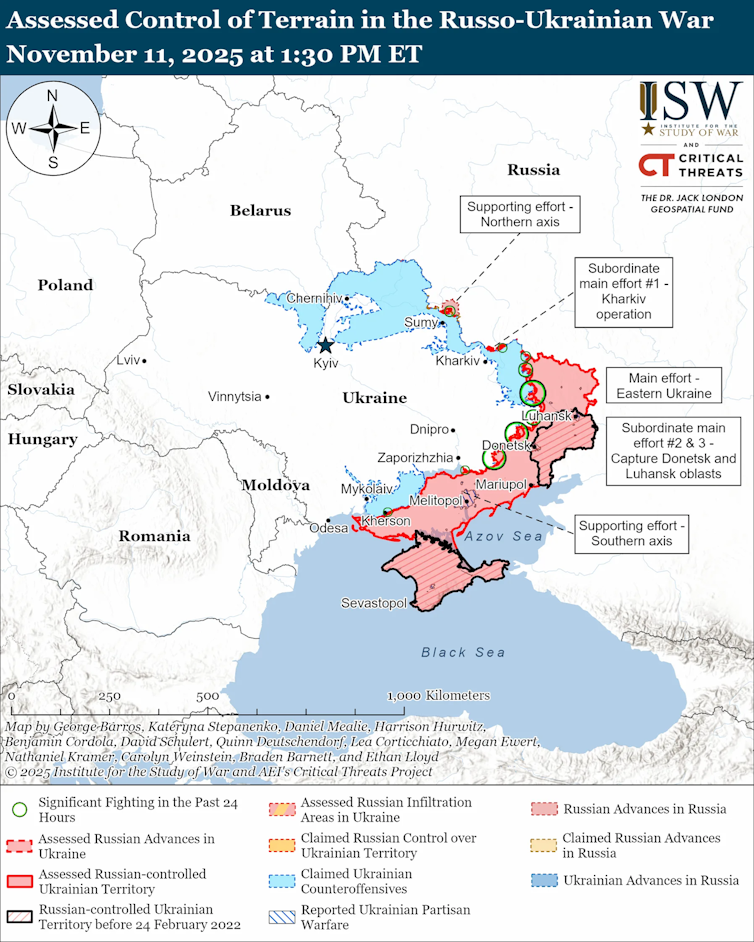

The situation on the front has been largely static for months, although Russian forces have been making small gains in some key areas. The battles for the strategically important cities of Pokrovsk in the Donetsk region of eastern Ukraine and Huliaipole in the southern region of Zaporizhzhia are a good indication of the progress of the war in general.

It’s hard, amid the flood of disinformation, to accurately monitor from a distance the exact status of these two important battles. Each day brings fresh reports of multiple attacks and advances by Russian troops. There have also been reports that Russian units have captured Pokrovsk. This would be a serious blow for Ukraine, as it’s an important supply hub, with several roads and rail lines converging there.

But the US-based military think-tank the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), which uses geolocated footage on which to base its assessments, has determined that Russia is not yet in full control of Pokrovsk, having to date seized 46% of the city. ISW analysts say Russian military bloggers are “mounting a concerted informational campaign prematurely calling the fall of Pokrovsk, likely to influence the information space”.

The battle for Pokrovsk has raged for nearly 18 months now, without resolution – but with huge casualties on both sides.

Similarly, while the situation in Huliaipole is deteriorating for the Ukrainian defenders, “Russian forces will probably spend considerable time setting conditions for efforts to seize the settlement”, the ISW says.

It’s important to realise that Russian troops initially entered Huliaipole on March 5 2022 within weeks of its initial invasion the previous month, but were quickly pushed back by Ukrainian troops. Fighting has continued in the region ever since.

In other words while both sides have made some tactical gains, neither holds the strategic upper hand.

One thing is clear: despite the claims and counter-claims, both sides have suffered significant casualties. In June 2025, the UK Ministry of Defence estimated more than one million Russian troops have been killed or injured since the invasion in February 2022. But Russia still retains considerable reserves of troops to call on, and has not yet had to resort to full mobilisation.

Meanwhile Russia’s economy is holding up, despite western sanctions. The effect of the recent imposition of oil sanctions by the US has yet to be seen. At the same time, Russia’s continuing and thriving diplomatic, economic and military relationships with its “enabler ally” China, as well as others on the anti-west axis such as Iran and North Korea – which have been supplying Moscow with weaponry and troops, respectively – is helping it sustain its offensive efforts.

Institute for the Study of War

Financing Ukraine’s defence

Ukraine, meanwhile, is now almost entirely reliant on continued western support. Since Donald Trump took power in the US in January, the US stance towards Ukraine has shifted considerably and while Kyiv’s friends in Nato can continue to purchase US weaponry for Ukraine’s war effort, the US will not fund any of the purchases. Consequently, military aid to Ukraine has slowed considerably in the second half of 2025 – by up to 43% according to German research non-profit the Kiel Institute.

EU leaders voted in October to meet Ukraine’s “pressing financial needs” for another two years, but have yet to agree on a way of doing that. Using frozen Russian assets comes with a number of difficulties. These assets are held in Belgium by the securities depository Euroclear. But Brussels is wary of the move, arguing that a Russian lawsuit against the move, if successful, could leave Belgium liable.

The other obstacle is that it would need to be unanimously approved by EU member states, something that is thought highly unlikely. The idea of using frozen Russian assets has already been rejected by Hungary and Slovakia. And the recent victory of the populist ANO party in the Czech Republic could signal further isolation for Ukraine. One of the first gestures made by the new Czech government has been to remove the Ukrainian flag from the parliament building.

If Norway were willing to use its US$2 trillion sovereign wealth fund to guarantee a €160 billion loan to Ukraine, it would effectively bypass the need for EU unanimity. But the country’s finance minister, former Nato secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg, appeared to rule that out on November 12 when he said guaranteeing the whole amount was “not an option”.

What impact is this loan likely to make in the grand scheme of things? The funds supplied thus far have kept Ukraine from defeat, but have not enabled it to strike a decisive blow against Russia that would win the war or enable it to negotiate a just peace.

At the same time it is realistic to acknowledge that while a massive injection of funds would help Ukraine stabilise its economy and buy enough arms to give their troops a better chance on the battlefield, it cannot deliver the manpower, weapons or morale. In the end, this latest wave of aid may buy Ukraine time – but it’s unlikely to deliver victory.

![]()

Veronika Hinman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Kyiv’s European allies debate ways of keeping the cash flowing to Ukraine but the picture on the battlefield is grim – https://theconversation.com/kyivs-european-allies-debate-ways-of-keeping-the-cash-flowing-to-ukraine-but-the-picture-on-the-battlefield-is-grim-269541