Source: The Conversation – in French – By Todd Pezzuti, Associate Professor of Marketing, Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez

De Lagos à Cape Town, de Santiago à Séoul, tout le monde veut être cool. « Cool » est un mot que l’on entend partout : dans la musique, dans la mode, sur les réseaux sociaux. Nous l’utilisons pour décrire certains types de personnes.

Mais qu’est-ce qui rend vraiment quelqu’un « cool » ? Est-ce juste une question de popularité ou de style ? Ou y a-t-il quelque chose de plus profond ?

Dans une étude récente menée avec d’autres professeurs de marketing, nous avons cherché à répondre à une question simple mais rarement posée. Quels sont les traits de personnalité et les valeurs qui rendent quelqu’un cool, et varient-ils d’une culture à l’autre ?

Nous avons interrogé près de 6 000 personnes dans 12 pays. Nous leur avons demandé de penser à quelqu’un qu’elles connaissaient personnellement et qu’elles trouvaient soit « cool », soit « pas cool », soit « une bonne personne », soit « une mauvaise personne ». Ensuite, elles devaient décrire les traits de caractère et les valeurs de cette personne avec des outils de psychologie validés. Nous avons utilisé ces données pour examiner en quoi le fait d’être cool diffère de la sympathie ou de la moralité en général.

L’étude a couvert des pays aussi divers que l’Australie, la Turquie, les États-Unis, l’Allemagne, l’Inde, la Chine, le Nigeria et l’Afrique du Sud.

Les résultats montrent qu’à travers le monde, la coolitude se caractérise par six traits essentiels : les personnes perçues comme cool sont généralement extraverties, portées sur le plaisir, aventurières, ouvertes d’esprit, puissantes et indépendantes.

Ces conclusions permettent d’éclaircir un débat de longue date : qu’est-ce qu’être cool à notre époque ?

Brève histoire de la coolitude

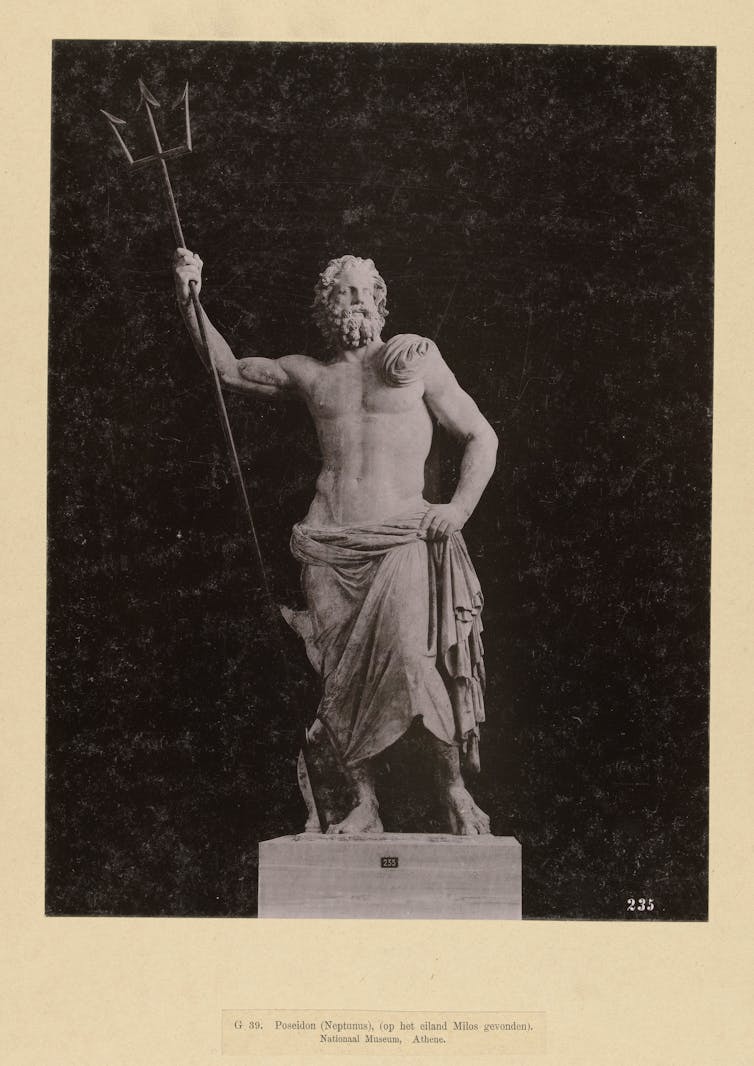

Les premiers écrits sur la « coolitude » la définissaient comme une forme de retenue émotionnelle : savoir rester calme, posé et impassible.

Certains chercheurs estiment que cette forme de « cool » remonte à l’époque de l’esclavage et de la ségrégation. Pour les Africains réduits en esclavage et leurs descendants, garder le contrôle de leurs émotions était une véritable stratégie de survie. Cette retenue devenait alors un symbole d’autonomie et de dignité face à l’oppression. D’autres pensent que cette attitude de maîtrise existait déjà bien avant l’esclavage.

Quoi qu’il en soit, ce sont les musiciens de jazz des années 1940 qui ont rendu ce style « cool » célèbre : une allure détendue, élégante et maîtrisée sur le plan émotionnel. Ce modèle a ensuite séduit la jeunesse et plusieurs mouvements contre-culturels. Au fil du temps, des marques comme Nike, Apple ou MTV ont récupéré cette attitude rebelle pour en faire un produit marketing. Ce qui était à l’origine un esprit marginal est devenu une esthétique mondiale, plus facile à vendre au grand public.

Ce qui rend quelqu’un cool

Nos conclusions suggèrent que la signification du mot « cool » a changé. C’est un moyen d’identifier et de cataloguer les personnes ayant un profil psychologique spécifique.

Les personnes cool sont extraverties et sociables. Elles recherchent le plaisir et la jouissance (hédonistes). Elles prennent des risques et essaient de nouvelles choses (aventurières). Elles sont curieuses et ouvertes à de nouvelles expériences (ouvertes). Elles ont de l’influence ou du charisme (puissantes). Et peut-être surtout, elles font les choses à leur manière (autonomes).

Cette conclusion est restée remarquablement la même dans tous les pays. Que l’on soit aux États-Unis, en Corée du Sud, en Espagne ou en Afrique du Sud, les gens ont tendance à penser que les personnes cool partagent le même « profil cool »..

Nous avons également constaté que même si le fait d’être cool recoupe le fait d’être bon ou sympathique, être cool et être bon ne sont pas la même chose. Être gentil, calme, traditionnel, sûr de soi et consciencieux était davantage associé à la bonté qu’à la coolitude. Certains traits associés à la coolitude, comme l’extraversion ou la recherche du plaisir, ne sont pas toujours vus comme des qualités morales.

Qu’en est-il de l’Afrique du Sud et du Nigeria ?

L’un des aspects les plus intéressants de notre étude est la régularité des résultats entre les cultures, même dans des pays aux valeurs et traditions très différentes.

En Afrique du Sud, les participants considéraient les personnes cool comme extraverties, hédonistes, puissantes, aventureuses, ouvertes et autonomes, tout comme les participants d’Europe et d’Asie. En Afrique du Sud, cependant, la coolitude se distingue particulièrement du fait d’être bon. L’Afrique du Sud est l’un des pays où être hédoniste, puissant, aventureux et autonome était a été associé au fait d’être cool que d’être une bonne personne.

Le Nigeria a montré des résultats un peu différents. C’était le seul pays où les personnes cool et pas cool étaient perçues comme également autonomes. En gros, l’individualité n’était pas considérée comme cool. Cette différence pourrait refléter des valeurs culturelles qui accordent une plus grande importance à la communauté, au respect des aînés ou à l’identité collective. Dans les sociétés où la tradition et la hiérarchie sont importantes, faire ce que l’on veut n’est pas forcément vu comme cool.

Cependant, comme toutes les sciences, les sciences sociales ne sont pas exactes. Il est donc raisonnable de supposer que l’autonomie est peut-être assoociée à la coolitude au Nigeria, mais que des biais d’enquête ou d’interprétation aient faussé les réponses.

Autre particularité : au Nigeria, la différence entre être cool et être bon était moins marquée qu’ailleurs. Là-bas, la coolitude est plus souvent perçue comme une qualité morale que dans les autres pays.

Pourquoi est-ce intéressant ?

Le fait que tant de cultures s’accordent sur ce qui rend quelqu’un cool suggère que la « coolitude » pourrait avoir une fonction sociale universelle. Les traits qui rendent les gens cool peuvent les pousser à essayer de nouvelles choses, à innover en matière de style et de mode, et à influencer les autres. Ces personnes repoussent souvent les limites et introduisent de nouvelles idées, que ce soit dans la mode, l’art, la politique ou la technologie. Elles inspirent les autres et contribuent à façonner ce qui est considéré comme moderne, désirable ou avant-gardiste.

Dans ce sens, la coolitude pourrait fonctionner comme une sorte de marqueur de statut culturel, une récompense pour l’audace, l’ouverture d’esprit et l’innovation. Être cool ne se limite pas à l’apparence : c’est avoir un temps d’avance et donner aux autres l’envie de suivre.

Que peut-on retenir de tout cela ?

D’une part, les jeunes d’Afrique du Sud, du Nigeria et du monde entier ont peut-être plus en commun que nous ne le pensons souvent. Malgré d’énormes différences culturelles, ils ont tendance à admirer les mêmes traits de caractère. Cela ouvre des pistes intéressantes pour mieux communiquer, collaborer et s’influencer à travers les cultures.

D’autre part, si on veut entrer en contact avec les autres ou les inspirer, que ce soit par l’éducation, l’image de marque ou le leadership, il est utile de comprendre ce que les gens considèrent comme cool. Le cool n’est peut-être pas une vertu universelle, mais c’est un langage universel.

Enfin, il y a dans tout cela quelque chose de rassurant : être cool ne dépend pas de la richesse ou de la célébrité. C’est une manière d’être.

Êtes-vous curieux ? Courageux ? Fidèle à vous-même ? Si oui, il y a de fortes chances que quelqu’un vous trouve cool, peu importe d’où vous venez.

![]()

Todd Pezzuti a reçu un financement de l’ANID Chili pour mener cette recherche.

– ref. Qu’est-ce qui rend une personne cool ? Une étude à l’échelle mondiale apporte quelques réponses – https://theconversation.com/quest-ce-qui-rend-une-personne-cool-une-etude-a-lechelle-mondiale-apporte-quelques-reponses-262067