Source: The Conversation – (in Spanish) – By Josep M. Trigo Rodríguez, Investigador Principal del Grupo de Meteoritos, Cuerpos Menores y Ciencias Planetarias, Instituto de Ciencias del Espacio (ICE – CSIC)

La pasada noche del 11 noviembre fue posible disfrutar desde toda Europa, Norteamérica y Centroamérica del espectáculo de las auroras. Desde España se han visto y fotografiado las llamadas auroras SAR (acrónimo de Arcos Rojos Estables o Stable Aurora Red arch), una especie de reflejo lejano de las que se dan a gran altura en latitudes boreales. Se aprecian como una luminosidad rojiza cercana al horizonte norte que se aprecia a simple vista, aunque las cámaras la captan maravillosamente dada su mayor sensibilidad.

Que veamos auroras SAR es normal, incluso que cambien de intensidad según el devenir de la actividad geomagnética. También se produjeron en mayo del año pasado, en un momento álgido (como ahora) de la actividad solar.

En estos momentos, el Sol se encuentra en una fase especialmente activa en la que sufre grandes erupciones, acompañadas de la emisión masiva de protones y partículas alfa (núcleos de helio) a grandes velocidades (algunas del orden de 1 800 km/s).

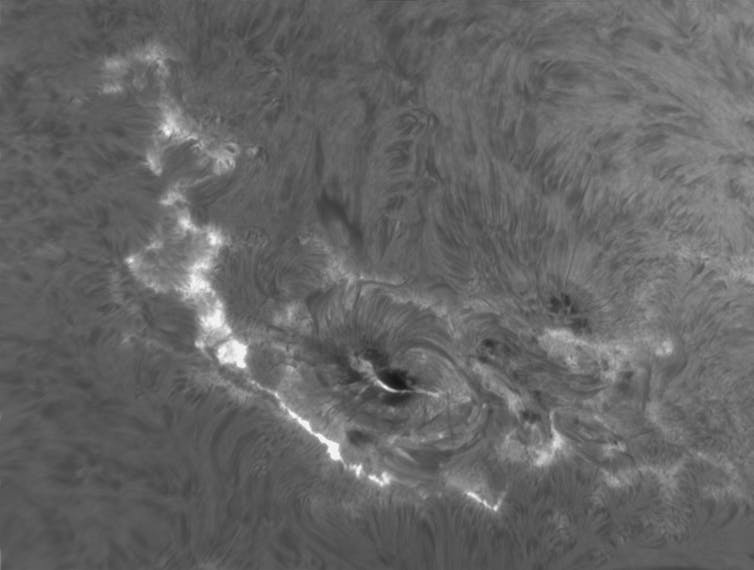

Muchos astrofotógrafos aprovechan estos días para tomar imágenes increíbles de la fotosfera solar que muestran la gran actividad del astro rey.

El origen de las auroras y sus preciosos colores

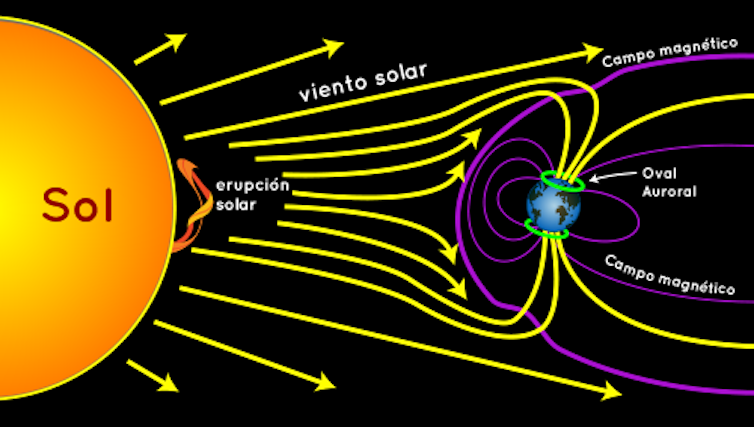

Tras la emisión de masa coronal del Sol, las partículas atómicas, en buena parte cargadas eléctricamente, pasan a formar parte del llamado viento solar y se difunden por el medio interplanetario. Esa gigantesca ola de átomos e iones tardará entre 1,5 y 4 días en llegar a la Tierra, en función de la velocidad de la ráfaga de masa coronal eyectada.

Nasa Space Place

Las energéticas partículas quedan retenidas en el campo magnético de nuestro planeta. Posteriormente, viajan por las líneas de dicho campo hasta golpear la atmósfera superior de la Tierra, cerca de los polos Norte y Sur. Cuando estos átomos interactúan con los gases de nuestra atmósfera, producen las auroras boreales y australes, respectivamente.

Y, aunque en latitudes medias como las de España se suelan ver únicamente las auroras SAR rojas, desde latitudes más boreales o australes es posible contemplar hermosas cortinas de colores. El cromatismo de los hermosos arcos de la luz que se mueven por el cielo dependen de las moléculas ionizadas que emiten esa luz. Por ejemplo, el oxígeno emite luz verde y roja, mientras que el nitrógeno molecular brilla intensamente en colores azules y púrpuras.

El Sol dispara y los planetas reciben

Precisamente, el 11 de noviembre hubo una enorme emisión de masa coronal desde la región solar activa catalogada AR14274. Debido a la magnitud de esa erupción, esperamos que haya actividad geomagnética extraordinaria también en las próximas noches.

Precisamente las regiones más activas están asociadas a los grupos de manchas solares, a veces vinculados a brillantes segmentos llamados fáculas. Desde esas regiones suelen producirse las erupciones solares, desencadenadas por los cambios magnéticos que tienen lugar en la fotosfera solar.

Albert Sànchez Caso/MPC442-Gualba Obs./AstroMontseny

Muy atentos a las próximas noches

Es una gran oportunidad para los astrofotógrafos, pero cualquiera que disponga de un teléfono móvil también puede capturar alguna imagen nocturna de pocos segundos si se apoya en algún objeto o tiene un buen pulso. Precisamente esta misma tarde, la del 12 de noviembre, ya desde el crepúsculo tendremos muchas posibilidades de volver a ver auroras SAR desde la península ibérica.

De hecho, podremos seguir en tiempo real la actividad geomagnética en esta página de la Universidad de Kioto (Japón). Una web muy útil para comprobar el grado de actividad geomagnética es Heliomon, creada por Josep Maria Llenas, director del Observatori Astronòmic i Meteorològic de Pujalt, en Barcelona.

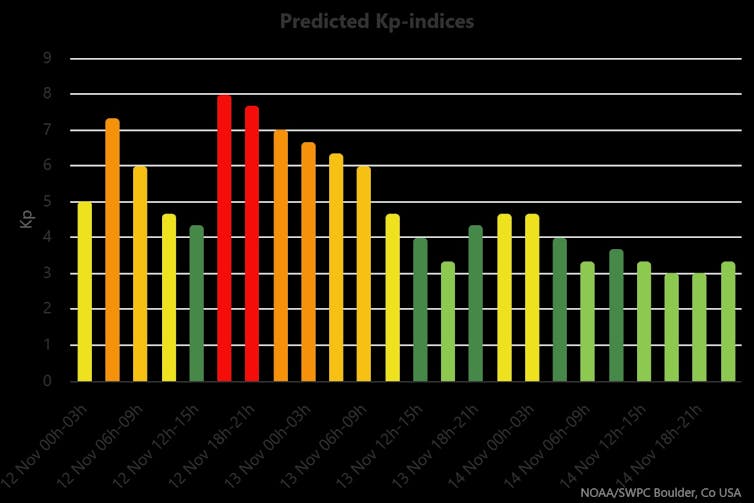

En particular existe un índice representativo de las condiciones geomagnéticas globales, conocido como Kp. Estos valores indican la actividad geomagnética esperada para cualquier período de tres horas durante los próximos tres días, como refleja la gráfica que sigue a este párrafo.

NOAA/SWPC Boulder, Col, EUA

Un buen ejemplo de las sesiones fotográficas que espero incentivar fue la realizada anoche por el astrofotógrafo Joan Manuel Bullón desde el pico de la Travina, en el municipio valenciano de Aras de Alpuente. Imágenes como esta precisamente me han animado a escribir el presente artículo para enfatizar que la próxima noche podría también ser histórica, una gran oportunidad para los amantes del tiempo (espacial).

Joan Manuel Bullón i Lahuerta

![]()

Josep M. Trigo Rodríguez recibe fondos del proyecto del Plan Nacional de Astronomía y Astrofísica PID2021-128062NB-I00 financiado por el MICINN y la Agencia Estatal de Investigación.

– ref. Así son las auroras rojas que han iluminado (y pueden volver a iluminar) los cielos de España y toda Europa – https://theconversation.com/asi-son-las-auroras-rojas-que-han-iluminado-y-pueden-volver-a-iluminar-los-cielos-de-espana-y-toda-europa-269614