Source: The Conversation – France (in French) – By Danièle Henky, Maître de conférences habilité à diriger les recherches en langues et littérature française (9e section) émérite, Université de Strasbourg

Des siècles passés, il reste l’histoire de nombreux talents féminins à exhumer. En avance sur leur temps, des femmes furent aussi capitaines d’industrie. Tel fut le cas de Marguerite de Wendel (1718-1802), née d’Hausen, qui devint, à partir de 1739, d’abord aux côtés de son mari puis seule, dirigeante des plus grandes forges françaises. Une main de fer dans un gant de velours… avec un caractère aussi trempé que l’acier.

Durant ce que l’on a appelé le « siècle des Lumières », l’éducation féminine fut mise à l’ordre du jour. Le recul de l’illettrisme réduisit l’écart dans l’alphabétisation entre les sexes. Dans un monde très marqué par les valeurs paternalistes, il restait difficile, cependant, d’être une femme et d’accéder aux savoirs. D’importantes barrières et contraintes limitaient les possibilités de conquérir les domaines masculins. La diffusion des savoirs allait favoriser, néanmoins, une évolution de la condition féminine.

On ne peut nier que de nombreuses femmes, parmi les classes privilégiées, jouèrent un rôle majeur dans divers domaines. Parmi elles, il y eut, notamment dans les milieux du commerce et de l’industrie, des épouses qui secondèrent leurs maris dans leurs charges professionnelles, se distinguant par leur acharnement au travail et leur intelligence des affaires.

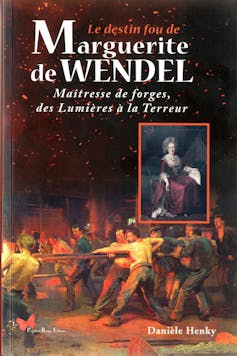

En avance sur la marche du temps, elles furent des chefs d’entreprise d’exception. Tel fut le cas, comme le révèlent les archives de la Maison de Wendel, de Marguerite d’Hausen qui devint, en 1739, Marguerite de Wendel (1718-1802). C’est ce que je retrace sa biographie le Destin fou de Marguerite de Wendel : maîtresse de forges, des Lumières à la Terreur (2021).

Épopée industrielle

Une véritable épopée industrielle, comme le narre l’historien René Sédillot. Elle commence avec Jean-Martin de Wendel (1665-1737), qui acheta en 1704 à Hayange, petit village mosellan, une forge à demi ruinée.

Originaire de Bruges, la famille s’était installée en Lorraine avec Christian de Wendel (1636-1708). Son fils cadet, Jean-Martin, devint directeur des forges d’Ottange, avant de débuter à Hayange cette lignée de maîtres de forges qui dirigea les entreprises de Wendel jusqu’en 1978. À la mort de ce pionnier, ses fils héritèrent de cinq forges en pleine activité.

Hal, Fourni par l’auteur

Le 10 mai 1739, Marguerite d’Hausen, née à Sarreguemines (Moselle) en 1718, fille du receveur des finances de Lorraine, épousa Charles de Wendel, de dix ans son aîné, maître de forges et seigneur d’Hayange. Il était l’un des fils de Jean-Martin, devenu conseiller secrétaire du roi en la chancellerie du parlement, anobli en 1727 par le duc Léopold. Lors de ce mariage, Jean Alexandre d’Hausen dota sa fille d’une somme de 60 000 livres, soit le double de ce que valait l’affaire Wendel en 1704.

Dès lors, grâce au travail et à la bonne gestion de Charles, l’affaire ne cessa de prospérer et de s’étendre. Lors de la guerre de succession d’Autriche (1740-1748) puis de la guerre de Sept Ans (1756-1763), sous le règne de Louis XV, les Wendel reçurent des commandes de boulets que les ouvriers façonnaient en coulant de la fonte liquide dans des moules sphériques. Ils fabriquaient aussi des affûts. De la platinerie sortaient des casques pour les cavaliers…

Main de fer dans un gant de velours

Bonne épouse et bonne mère, Marguerite de Wendel eut sept enfants dont cinq survécurent. Elle n’en eut pas moins la curiosité de s’intéresser aux affaires de son mari, aux nouvelles techniques et à l’univers inconnu pour elle de la sidérurgie.

Elle a d’abord relayé par nécessité son époux, toujours en voyage pour trouver de nouveaux marchés et de nouveaux financements. Il lui a appris à surveiller les coulées de fonte des hauts fourneaux et à diriger les ouvriers mieux qu’un contremaître aguerri. À une époque où beaucoup de femmes de son milieu ne se préoccupaient que de leurs galants ou de leurs toilettes, elle conduisit les forges en capitaine d’industrie : une main de fer dans un gant de velours !

Veuve de Charles de Wendel en 1784, celle qu’on a appelée Madame d’Hayange resta seule face à la tourmente révolutionnaire qu’elle affronta du mieux qu’elle put. Secondée par ses gendres, Alexandre de Balthazar et Victor de la Cottière, elle surveillait les hauts-fourneaux, veillait à la commercialisation des produits manufacturés et se réservait la responsabilité des relations avec les autorités politiques. Il fallut se battre avec les bureaux de Versailles pour faire payer les fournitures livrées aux armées. Marguerite en s’acharnant parvint à tenir renégociant en 1788 les contrats avec les arsenaux royaux. Elle obtint des conditions plus avantageuses que celles acquises de haute lutte par Charles.

Terreur révolutionnaire

En 1789, les révolutionnaires eurent besoin, comme la monarchie avant eux, des armes sortant des usines de Wendel. Protégée par l’armée, « Madame d’Hayange » fut en revanche en butte aux rancœurs de certains habitants de la ville, à commencer par l’ancien cocher du château, Jacques Tourneur. La Révolution en fit un maire qui ne cachait pas le mépris que lui inspiraient les « ci-devant » – les personnes ayant bénéficié d’un privilège « avant ». Ayant demandé un jour qu’on lui fournisse des chevaux pour livrer les munitions d’artillerie, la « citoyenne Wendel » se vit répondre par la municipalité d’utiliser les chevaux de son carrosse.

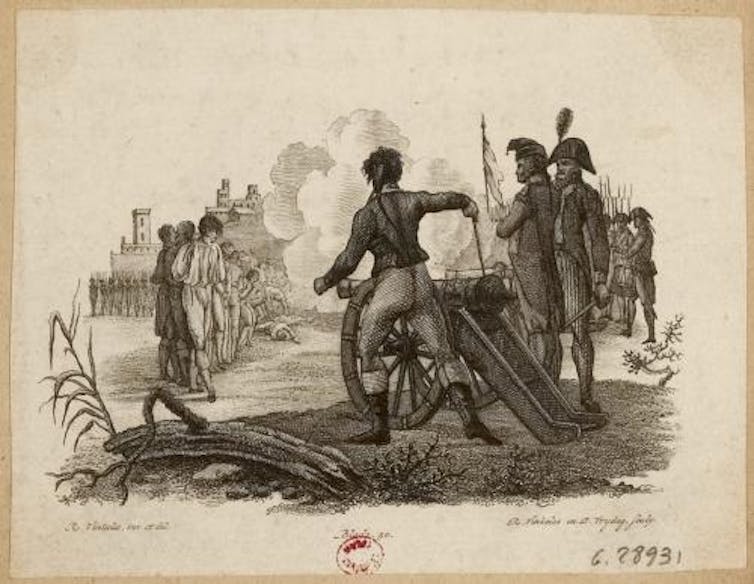

Musée Carnavalet

Dès les débuts de la Terreur (5 septembre 1793-28 juillet 1794), sa vie devint un enfer. Son petit-fils, accusé de collusion avec l’ennemi, fut guillotiné à Metz, le 25 octobre 1793. Restée seule après le départ des siens, Marguerite poursuivit sa mission, contre vents et marées, en obtenant du représentant du peuple à l’armée de Moselle qu’on ne réquisitionne aucun des biens ou des ouvriers utiles à la fabrication des boulets de canon. Elle passa ses journées et parfois ses nuits aux forges, surveillant la coulée aux côtés des contremaîtres et des ouvriers.

Caractère aussi trempé que l’acier

Dans les convulsions d’une époque qui, après l’optimisme scientiste des Lumières, fut plongée dans les abominations de la Terreur, cette femme au caractère aussi trempé que l’acier, incarnait un bel exemple d’énergie féminine au service de sa famille, de son entreprise et de son pays.

Cela n’empêcha pas la mise sous séquestre de tous ses biens, ni sa mise en accusation, le 14 germinal An II (3 avril 1794), pour avoir favorisé l’émigration de ses fils, comme le rappelle l’historien Jacques Marseille. Emprisonnée à Metz puis à Sarreguemines, elle fut de retour à Hayange, le 6 octobre 1795, pour constater que les hauts fourneaux étaient éteints et les forges à l’abandon.

Bientôt, les forges de Wendel furent vendues aux enchères pour payer des dettes. Très affaiblie par son incarcération, logée dans un petit appartement de la rue des Prisons militaires (aujourd’hui, rue Maurice-Barrès) à Metz (Moselle), Marguerite n’eut de cesse de se battre pour tenter de récupérer son entreprise.

Elle s’éteignit le 4 janvier 1802, laissant quelques habits usés et de modestes meubles en sapin sans avoir eu le bonheur de voir la résurrection de sa Maison.

« La dame du fer »

Cette maîtresse des forges n’a rien à envier aux hommes par son incroyable capacité à mener à bien coulées de fonte et opérations de laminage. Elle a su aussi diriger des équipes d’ouvriers et des contremaîtres aussi bien que son époux. Ne la connaissait-on pas sous le nom de « la dame du fer » ? Sa pugnacité mais aussi son sens de la gestion comme ses connaissances en droit lui permirent de gagner des procès difficiles. Elle n’hésita pas à rencontrer les politiques nécessaires à la bonne marche de son entreprise et aurait pu, sans la Terreur, laisser à ses héritiers une entreprise prospère.

Ce fut indubitablement une pionnière, mais elle n’en a sans doute pas eu conscience, tant le féminisme ne pouvait se concevoir encore. Au début, elle a seulement voulu relayer son époux. Aurait-elle pu entreprendre tout ce qu’elle a fait, cependant, si elle n’y avait pas pris goût ? Elle aimait son travail, investissait, se lançait dans des projets en étant force de proposition face à ses fournisseurs. Elle a accompli son destin sans état d’âme en mobilisant toutes ses ressources. Par son exemple, elle a montré tout naturellement, sans avoir besoin de faire de longs discours, ce dont une femme est capable si on lui laisse le champ libre.

Droits des femmes

Au cours du XVIIIe siècle, certaines femmes profitèrent des temps si particuliers de la Révolution pour tenter de défendre leurs droits, pendant que des figures d’exception marquèrent l’histoire des arts, des sciences ou du pouvoir.

Comment ne pas évoquer Olympe de Gouges reconnue comme l’une des premières féministes françaises ? En proclamant les droits des femmes, elle posa des questions qui participèrent aux luttes à venir, au moment où le statut civil des citoyennes, pour un temps, s’améliorait. C’est à cette époque que vécut Marguerite de Wendel qui n’est pas connue comme une militante pour l’égalité des sexes, mais qui a largement montré par son comportement à quel point les femmes méritaient de voir leur condition évoluer.

![]()

Danièle Henky ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. Marguerite de Wendel, « la dame du fer » des forges françaises, une capitaine d’industrie d’exception – https://theconversation.com/marguerite-de-wendel-la-dame-du-fer-des-forges-francaises-une-capitaine-dindustrie-dexception-262353