Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Thanh-Son Pham, ARC DECRA Fellow in Geophysics, Australian National University

Glacial earthquakes are a special type of earthquake generated in cold, icy regions. First discovered in the northern hemisphere more than 20 years ago, these quakes occur when huge chunks of ice fall from glaciers into the sea.

Until now, only a very few have been found in the Antarctic. In a new study soon to be published in Geophysical Research Letters, I present evidence for hundreds of these quakes in Antarctica between 2010 and 2023, mostly at the ocean end of the Thwaites Glacier – the so-called Doomsday Glacier that could send sea levels rising rapidly if it were to collapse.

A recent discovery

A glacial earthquake is created when tall, thin icebergs fall off the end of a glacier into the ocean.

When these icebergs capsize, they clash violently with the “mother” glacier. The clash generates strong mechanical ground vibrations, or seismic waves, that propagate thousands of kilometres from the origin.

What makes glacial earthquakes unique is that they do not generate any high-frequency seismic waves. These waves play a vital role in the detection and location of typical seismic sources, such as earthquakes, volcanoes and nuclear explosions.

Due to this difference, glacial earthquakes were only discovered relatively recently, despite other seismic sources having been documented routinely for several decades.

Varying with the seasons

Most glacial earthquakes detected so far have been located near the ends of glaciers in Greenland, the largest ice cap in the northern hemisphere.

The Greenland glacial earthquakes are relatively large in magnitude. The largest ones are similar in size to those caused by nuclear tests conducted by North Korea in the past two decades. As such, they have been detected by a high-quality, continuously operating seismic monitoring network worldwide.

The Greenland events vary with the seasons, occurring more often in late summer. They have also become more common in recent decades. The signs may be associated with a faster rate of global warming in the polar regions.

Elusive evidence

Although Antarctica is the largest ice sheet on Earth, direct evidence of glacial earthquakes caused by capsizing icebergs there has been elusive. Most previous attempts to detect Antarctic glacial earthquakes used the worldwide network of seismic detectors.

However, if Antarctic glacial earthquakes are of much lower magnitude than those in Greenland, the global network may not detect them.

In my new study, I used seismic stations in Antarctica itself to look for signs of these quakes. My search turned up more than 360 glacier seismic events, most of which are not yet included in any earthquake catalogue.

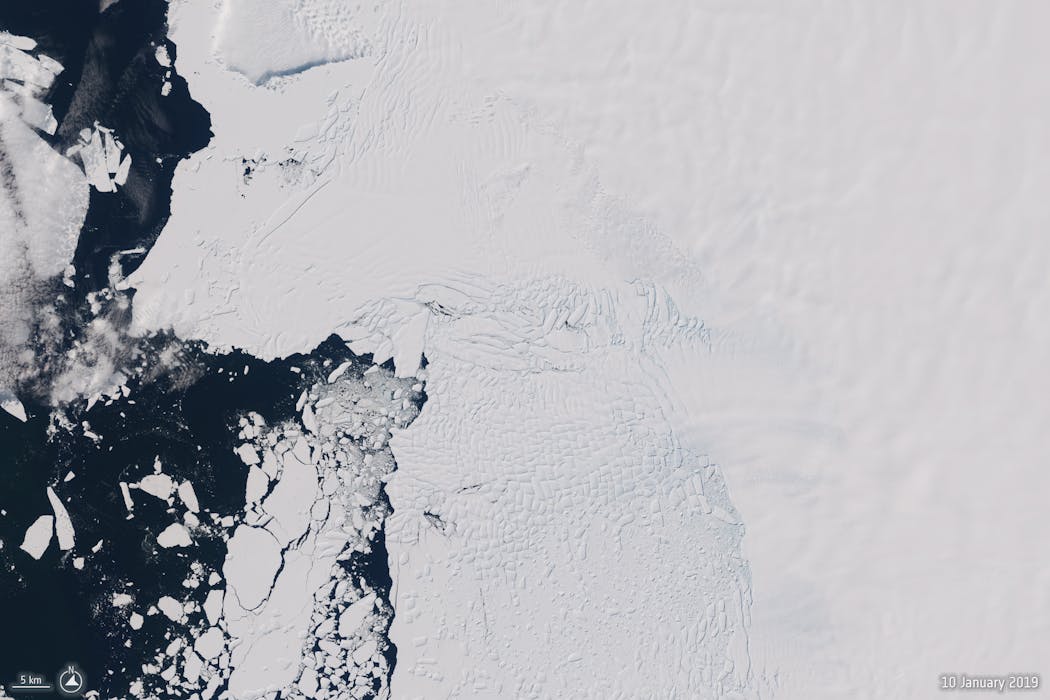

The events I detected were in two clusters, near Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers. These glaciers have been the largest sources of sea-level rise from Antarctica.

Earthquakes at the Doomsday Glacier

Thwaites Glacier is sometimes known as the Doomsday Glacier. If it were to collapse completely it would raise global sea levels by 3 metres, and it also has the potential to fall apart rapidly.

About two-thirds of the events I detected – 245 out of 362 – were located near the marine end of Thwaites. Most of these events are likely glacial earthquakes due to capsizing icebergs.

The strongest driver of such events does not appear to be the annual oscillation of warm air temperatures that drives the seasonal behaviour of Greenland glacier earthquakes.

Instead, the most prolific period of glacial earthquakes at Thwaites, between 2018 and 2020, coincides with a period of accelerated flow of the glacier’s ice tongue towards the sea. The ice-tongue speed-up period was independently confirmed by satellite observations.

This speed-up could have been caused by ocean conditions, the effect of which is not yet well understood.

The findings suggest the short-term scale impact of ocean states on the stability of marine-terminating glaciers. This is worth further exploration to assess the potential contribution of the glacier to future sea-level rise.

The second largest cluster of detections occurred near the Pine Island Glacier. However, these were consistently located 60–80 kilometres from the waterfront, so they are not likely to have been caused by capsizing icebergs.

These events remain puzzling and require follow-up research.

What’s next for Antarctic glacial earthquake research

The detection of glacial earthquakes associated with iceberg calving at Thwaites Glacier could help answer several important research questions. These include a fundamental question about the potential instability of the Thwaites Glacier due to the interaction of the ocean, ice and solid ground near where it meets the sea.

Better understanding may hold the key to resolving the current large uncertainty in the projected sea-level rise over the next couple of centuries.

![]()

Thanh-Son Pham receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

– ref. Hundreds of iceberg earthquakes detected at the crumbling end of Antarctica’s Doomsday Glacier – https://theconversation.com/hundreds-of-iceberg-earthquakes-detected-at-the-crumbling-end-of-antarcticas-doomsday-glacier-268893