Source: The Conversation – in French – By Hugo Spring-Ragain, Doctorant en économie / économie mathématique, Centre d’études diplomatiques et stratégiques (CEDS)

Vendredi 12 décembre 2025, le Groupe d’experts sur le smic publie un rapport sur l’impact du salaire minimum sur l’économie française. Son impact sur la pauvreté n’est cependant pas univoque. Le smic ne suffit pas à expliquer les trajectoires personnelles de plus en plus diverses. Le revenu disponible qui prend en compte les aides perçues et les dépenses contraintes est un critère plus juste.

La question revient cette année encore avec le rapport du Groupe d’experts du smic publié ce vendredi 12 décembre : le salaire minimum protège-t-il encore réellement de la pauvreté ? Pourtant, comme l’ont rappelé l’Insee et l’Institut des politiques publiques (IPP) dans plusieurs travaux plus ou moins récents, le salaire brut, seul, ne détermine pas la pauvreté. Ce qui importe, c’est le niveau de vie, c’est-à-dire le revenu disponible après transferts sociaux de toutes sortes (qui s’ajoutent), impôts et charges contraintes (qui se soustraient). Dans un contexte de renchérissement du logement (13 % d’augmentation de l’indice de référence des loyers, IRL) et d’hétérogénéité croissante des situations familiales, la question ne doit plus être posée en termes uniquement macroéconomiques.

La littérature académique reprend ce constat. Antony B. Atkinson souligne que la pauvreté ne renvoie pas simplement à un « manque de salaire », mais à un insuffisant accès aux ressources globales ; Patrick Moyes rappelle que la structure familiale modifie profondément le niveau de vie relatif. Quant à France Stratégie et l’Insee, après sa publication faisant l’état des lieux de la pauvreté en France, ils documentent la montée de ce qu’on appelle la pauvreté laborieuse, c’est-à-dire le fait de travailler sans pour autant dépasser les seuils de pauvreté et sans possibilité de profiter de l’ascenseur social.

À lire aussi :

La pauvreté de masse : symptôme d’une crise de la cohésion sociale

Un amortisseur d’inflation ?

Notre premier graphique compare l’évolution du smic, des salaires et des prix depuis 2013. On y observe très nettement que le salaire minimum a servi d’amortisseur pendant la séquence inflationniste récente : ses revalorisations automatiques l’ont fait progresser aussi vite, souvent plus vite, que l’indice des prix à la consommation.

Figure 1 – Évolution du smic, du salaire mensuel de base (SMB), du salaire horaire de base des ouvriers et des employés (SHBOE) et de l’indice des prix à la consommation (IPC) hors Tabac – Sources : Dares, Insee, Rapport GES 2025 – Graphique de l’auteur.

Ce mouvement contraste avec celui des salaires moyens, dont la progression a été plus lente. Comme le soulignent plusieurs analyses de France Stratégie et de l’Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques (OCDE), cela a eu pour effet de resserrer la hiérarchie salariale, une situation déjà documentée lors de précédentes périodes de rattrapage du smic.

L’influence du temps de travail

Mais ce constat ne dit rien d’une dimension pourtant déterminante : l’accès au temps plein car une partie des salariés au smic n’y est pas à temps complet. Comme l’ont montré plusieurs travaux de l’Insee et de la direction de l’animation de la recherche, des études et des statistiques (Dares, ministère du travail), une proportion importante de travailleurs rémunérés au salaire minimum occupe des emplois à temps partiel, et souvent non par choix mais parce qu’aucun temps plein n’est disponible. C’est ce que les économistes appellent le temps partiel contraint.

Ce temps partiel modifie radicalement l’interprétation du smic : on parle d’un salaire minimum horaire, mais, concrètement, les ressources mensuelles ne reflètent pas ce taux. Un salaire minimum versé sur 80 % d’un temps plein ou sur des horaires discontinus conduit mécaniquement à un revenu inférieur et donc à une exposition accrue à la pauvreté.

Mais si l’on s’en tenait à cette comparaison, on pourrait conclure que le smic protège pleinement les salariés les plus modestes. Or, c’est précisément ici que la question se complexifie. Car la pauvreté ne dépend pas du seul salaire : elle dépend du revenu disponible et donc de l’ensemble des ressources du ménage. C’est ce que montrent les travaux sur la pauvreté laborieuse, un phénomène en hausse en France selon l’Observatoire des inégalités, environ une personne en situation de pauvreté sur trois occupe un emploi mais les charges familiales, le coût du logement ou l’absence de second revenu maintiennent le ménage sous les seuils de pauvreté.

Du smic au revenu disponible

Pour comprendre la capacité réelle du smic à protéger de la pauvreté, il faut observer ce qu’il devient une fois transformé en revenu disponible grâce aux données de l’Insee et de la Dares, c’est-à-dire le revenu après impôts, aides et charges incompressibles.

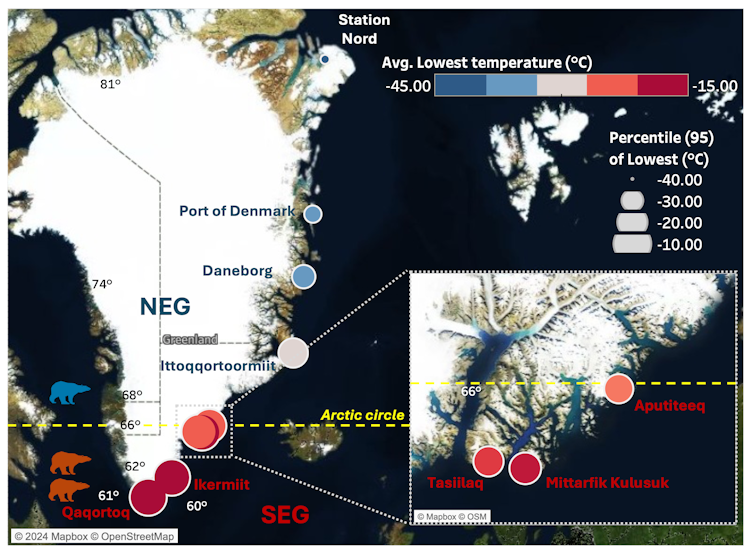

Le graphique suivant juxtapose trois situations familiales : une personne seule, un parent isolé avec un enfant et un couple avec un enfant dont les deux adultes perçoivent le smic.

Figure 2 – Revenu disponible et seuils de pauvreté selon trois profils de ménages rémunérés au smic Sources : Dares, Insee, Rapport GES 2025 – Graphique de l’auteur.

Dans le premier panneau, on observe qu’une personne seule rémunérée au smic dispose d’un revenu disponible supérieur au seuil de pauvreté à 60 % du revenu médian. La prime d’activité joue un rôle important, mais c’est surtout l’absence de charge familiale et de coûts fixes élevés qui explique ce résultat.

Ce profil correspond à la représentation classique du smic comme filet de sécurité individuel. Comme le confirment les données de l’Insee et les travaux de France Stratégie, la pauvreté laborieuse y est encore relativement limitée. Cependant, même seul, un actif au smic pourrait avoir des dépenses contraintes extrêmement élevées dans des zones à forte demande locative.

La pauvreté laborieuse

Le deuxième panneau raconte une histoire totalement différente. Le parent isolé, même à temps plein au smic se situe clairement en dessous du seuil de pauvreté, plus grave encore, son revenu disponible ne compense plus le salaire net via les transferts. C’est ici que la notion de pauvreté laborieuse prend tout son sens. Malgré un emploi et malgré les compléments de revenu, le ménage reste dans une situation de fragilité structurelle.

Selon l’Insee, les familles monoparentales sont aujourd’hui le groupe le plus exposé à la pauvreté et notamment à la privation matérielle et sociale, non parce qu’elles travaillent moins, mais parce qu’elles cumulent un revenu unique, des charges plus élevées et une moindre capacité d’ajustement.

Dans le troisième panneau, un couple avec un enfant et deux smic vit lui aussi en dessous de la ligne de pauvreté. Ce résultat laisse penser que la composition familiale, même accompagnée de deux smic crée une pauvreté structurelle sur les bas revenus ; aussi le graphique montre-t-il que la marge est finalement assez limitée. Une partie du gain salarial disparaît en raison de la baisse des aides et de l’entrée dans l’impôt, un phénomène bien documenté par l’IPP et par le rapport Bozio-Wasmer dans leurs travaux sur les « taux marginaux implicites ». Dans les zones de loyers élevés, un choc de dépense ou une hausse de charges peut faire basculer ces ménages vers une situation beaucoup plus précaire.

Situations contrastées

Une conclusion s’impose : le smic protège encore une partie des salariés contre la pauvreté, mais ce résultat est loin d’être uniforme. Il protège l’individu à plein temps et sans enfant, mais ne suffit plus à assurer un niveau de vie décent lorsque le salaire doit couvrir seul les charges d’un foyer, notamment dans les configurations monoparentales. Cette asymétrie est au cœur de la montée de la pauvreté laborieuse observée par l’Insee et documentée par l’Institut des politiques publiques.

Ces résultats rappellent que la pauvreté n’est plus seulement un phénomène d’exclusion du marché du travail. Elle touche des travailleurs insérés, qualifiés et en contrat stable, mais dont le salaire minimum, appliqué sur un volume horaire insuffisant ou absorbé par des dépenses contraintes, ne permet plus un niveau de vie supérieur aux seuils de pauvreté. Le smic se révèle alors davantage un plancher salarial individuel qu’un instrument de garantie sociale familiale.

À l’heure où la question du pouvoir d’achat occupe une place centrale et où la revalorisation du smic reste l’un des outils majeurs d’ajustement, ces conclusions invitent à réorienter le débat. Ce n’est pas seulement le niveau du smic qu’il faut interroger, mais sa capacité à constituer un revenu de référence pour des configurations familiales et territoriales très hétérogènes. Autrement dit, le smic joue encore sa fonction de stabilisateur individuel, mais il n’est plus suffisant seul pour protéger durablement certains ménages.

La question devient alors moins « De combien augmenter le smic ? » que « Comment garantir que le revenu disponible issu d’un emploi au smic permette effectivement d’éviter la pauvreté ? ».

![]()

Hugo Spring-Ragain ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. Le smic protège-t-il encore de la pauvreté ? – https://theconversation.com/le-smic-protege-t-il-encore-de-la-pauvrete-271245