Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Brian Mittendorf, Professor of Accounting, The Ohio State University

Charitable giving in the United States has changed significantly in recent years.

Two of the biggest changes are the swift growth of donor-advised funds and the increasingly blurred lines between charity and politics.

Donor-advised funds, or DAFs, are charitable investment accounts. After donors put money or other financial assets into these accounts, the assets are technically no longer theirs. But they do get a say in how those funds are invested, as well as when and which charities should get some of the money.

Americans gave nearly US$90 billion to DAFs in 2024 – up from the $20 billion DAFs took in a decade earlier.

One distinguishing feature about DAF donors is that when they dispatch money from their charitable accounts, they fund politically engaged charities at higher rates than people who give directly to charity.

That’s what we, two scholars who research the flow of money between donors and nonprofits, found when we conducted a study examining the links between donor-advised funds and donations to charities that are politically active. Our results will be published in a forthcoming issue of Nonprofit Policy Forum, a peer-reviewed academic journal.

Resembling family foundations

As charitable investment accounts, donor-advised funds straddle a middle ground between family foundations and organizations doing direct charitable work.

Like foundations, DAFs give donors a sense of long-term control over funds they’ve designated for charitable spending in the future. But because DAFs are accounts held within certified public charities, often those affiliated with financial institutions like Fidelity and Vanguard, they offer added tax benefits and simplicity.

DAFs let donors take charitable tax deductions immediately, and then decide later how much of that money to give to which charity – and when – by telling the account managers what to do.

Timing gifts this way can increase the tax advantages tied to charitable giving through tax deductions. And DAFs help donors do this without the expenses, staffing and complexity of running their own foundations.

These advantages – coupled with persuasive marketing campaigns – have helped spur a DAF boom. Donor-advised funds held $326 billion in 2024.

More politically engaged charitable activity

We consider charities “politically engaged” if they either do lobbying or have related organizations that participate in political campaigning. These groups span the political spectrum: For example, they include both the National Rifle Association and the Environmental Defense Fund.

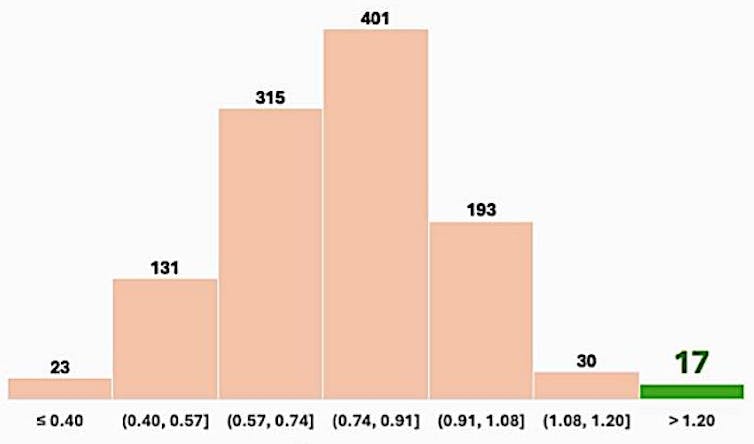

We gathered data from the nearly 250,000 charities in the U.S. that filed a 990 form with the Internal Revenue Service from 2020 to 2022. The country’s largest charities must file these informational forms annually and make them available to the public.

When we crunched the numbers, we discovered that nearly 6% of payments from DAF accounts go to politically engaged charities. In comparison, other funding sources paid out only 3.6% to politically engaged charities.

This means a funding rate from DAFs is 1.7 times the benchmark level. When it comes to fringe hate and antigovernment charities, overall funding levels are low, but the DAF difference is more pronounced – DAF donors fund these groups at a rate 3.5 times that of other donors.

Giving donors more privacy

One other advantage DAFs offer donors is that they provide more anonymity than if donors give to a cause directly.

Under current disclosure rules, when donors give more than $5,000 to any charitable nonprofit – whether it’s their local food bank or animal shelter or art museum – both the charity and the IRS have to know who they are. When donors give that much to private foundations, it becomes part of the public record as well.

But when donors give any amount, even if it’s much more than $5,000, through their DAFs, even the charity that ultimately gets the money may not know the donor’s identity.

This anonymity may be one reason donors more often use DAFs to give to organizations that engage in politics, either directly or indirectly.

To be sure, charities are permitted to engage in different types of political engagement to varying degrees. In fact, U.S. charities have long been important public policy advocates. And it is also understandable that donors might want to be anonymous. Yet the use of DAFs to provide gifts to fringe groups suggests this lack of transparency is not always a good thing.

The rules around donor disclosure were originally set up to prevent private interests from abusing the system.

This is the reason that foundations – like those set up by tech billionaire Elon Musk or Google co-founder Larry Page – must publicly disclose both their major donors and their grant recipients.

But when these foundations make grants to donor-advised funds, the digital trail becomes a dead end. The public has no way to know which charities the foundations are ultimately funding with their grants after the money enters a DAF’s coffers.

Consistent with this arrangement, we found that the DAFs that get more grants from foundations tend to fund politically active organizations at higher rates.

Changing the charity landscape

As DAFs continue to expand, further research can help cast light on what effect they will ultimately have. Though much research and many proposed new rules have focused on whether Americans need to move the money in their DAFs out to charities more quickly, we’re focused on where that money goes.

In examining tax filings, we have also learned that some charitable sectors get more money from DAFs than others.

For example, social service nonprofits, which include homeless shelters and food banks, get 25% of all giving, but only 20% of DAF giving. This may seem like a small difference, but it can actually represent seismic shifts in where charitable dollars go.

And we’re now examining whether the size of a charity’s DAF program can influence that organization’s behavior. The data collected from 990 forms suggests that even community foundations may become less focused on their local communities when they court DAF donors.

![]()

Helen Flannery is employed by the Institute for Policy Studies, a progressive think tank that has done research related to charity reforms.

Brian Mittendorf does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Donor-advised funds have more money than ever – and direct more of it to politically active charities – https://theconversation.com/donor-advised-funds-have-more-money-than-ever-and-direct-more-of-it-to-politically-active-charities-270758