Source: The Conversation – USA – By Linda Bartoshuk, Research Professor of Psychology, George Washington University

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

Why does orange juice taste bad after you brush your teeth? – Seth G., age 10, Bloomington, Indiana

It’s a mistake you hopefully only make once. In your morning rush to get ready, you brush your teeth before you head to the kitchen and down a big glass of orange juice. Yuck!

What makes your clean, minty mouth taste so gross when it meets OJ?

The short answer is that toothpaste contains a detergent that dissolves fat. And since your taste buds are partly made of fat, they are disrupted whenever you brush your teeth.

Before you decide you need to stop brushing your teeth to save your taste buds, know that this disruption is temporary, lasting only a few minutes. Brushing with toothpaste is still important for your health.

But how does this change in taste happen? And how are the taste receptors that are all over the surface of your tongue supposed to work?

I’m a psychologist, and I’ve spent more than 40 years researching the science of how people experience taste and flavor.

Let’s look at the science behind this phenomenon:

A bittersweet symphony

Thanks to evolution, your brain is wired to make you love the sweet sugars your body and brain need for fuel and hate the bitter poisons than could kill you. So your receptors for these two particular tastes are vital to your survival.

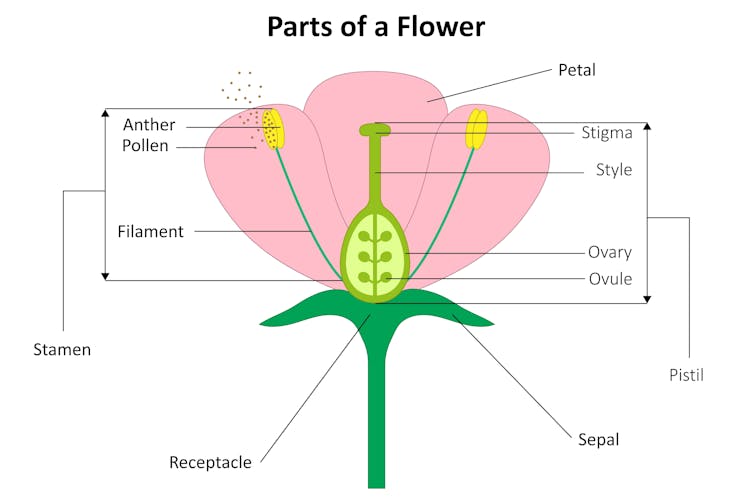

All of the cells in your body are held together by an outer layer, known as the membrane, that is made up of fats called lipids. And in sweet or bitter taste receptor cells, the cell membranes also contain a special molecule called a G protein-coupled receptor, or GPCR.

Some GPCRs are designed to detect sweet tastes. They tune out all compounds that aren’t sweet and respond only to the sugars your body can use. Others detect bitter tastes, tuning in to the large number of compounds in nature that are poisonous. They act as a built-in alarm system.

Salty chips and sour candies

Your perception of saltiness and sourness happens a little differently. These tastes are detected when positively charged ions called cations pass through tiny openings in the cell membrane of your salty and sour receptors.

In the case of saltiness, the cation is the positively charged sodium found in sodium chloride – common table salt.

For acidic, or sour, tastes, the cation is a positively charged hydrogen ion. While different types of acids may contain different chemical compounds, they all contain the hydrogen cation.

When you eat potato chips, the positively charged sodium cations from the salt pass through special openings in a receptor’s membrane, producing the salty taste. Similarly, the hydrogen cations in your favorite sour candy slip through other special openings in your sour receptor’s membrane and send a “sour” signal to your brain.

Toothpaste and OJ

The orange juice that many people like to drink with breakfast is naturally high in sugar. But it also contains citric acid, with its hydrogen cations. As a result, it’s a delicious combination of both sweet and a little sour.

But if you brush your teeth before breakfast, your OJ tastes terrible. What’s changed?

It’s not just that minty tastes clash with sweet ones. Toothpaste contains the detergent sodium lauryl sulfate, which helps remove dental plaque from your teeth. Plaque is the sticky film of germs that can cause cavities and make your breath smell bad.

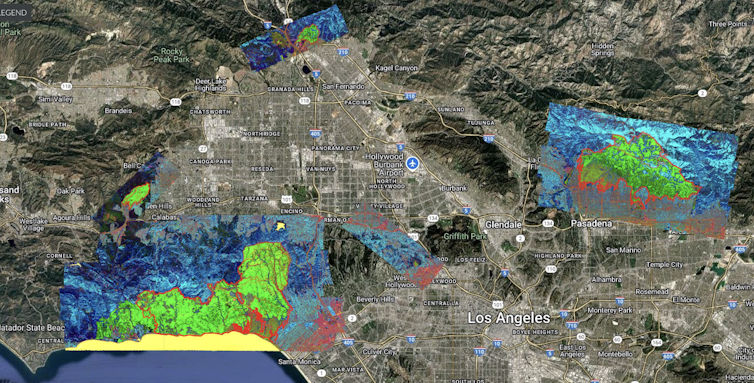

Ekaterina Goncharova/Moment via Getty Images

If you ever do the dishes, you’ve probably seen what happens when you squirt detergent into a sink full of greasy water: The detergent breaks up the greasy fat, making it easy to wipe it off the dishes and rinse them clean.

But there’s another type of fat in your mouth that the detergent in toothpaste disrupts – the lipids in the cell membranes of your taste receptors. Brushing your teeth breaks up that layer of lipids, temporarily changing how you perceive taste.

Testing it out

Back in 1980, I conducted a study with a couple of my colleagues who were studying chemistry. We wanted to know how the tongue responds to sweet, bitter, salty and sour after being exposed to sodium lauryl sulfate, the detergent in toothpaste.

We conducted an experiment with seven student volunteers at Yale. They tasted very high concentrations of sweet sucrose, sour citric acid, salt and bitter quinine, both before and after holding a solution (0.05%) of sodium lauryl sulfate in their mouths for one minute.

You could conduct your own version of this experiment with something sweet like sugar, a little table salt, orange juice and tonic water. Taste them before you brush your teeth and then after, and see what happens!

We found that the intensity of the tastes of sucrose, salt and quinine were reduced by a small amount, but the most important change was that a bitter taste was added to the sour taste of citric acid.

This is why, instead of tasting sweet with a bit of nice tanginess, your OJ tastes bitter after you brush your teeth.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

![]()

Linda Bartoshuk has received funding from NIH.

– ref. Why does orange juice taste bad after you brush your teeth? – https://theconversation.com/why-does-orange-juice-taste-bad-after-you-brush-your-teeth-271741