Source: The Conversation – USA – By Alexander L. Metcalf, Associate Professor of Human Dimensions of Natural Resources, University of Montana

Management of gray wolves (Canis lupus) has a reputation for being one of the most contentious conservation issues in the United States. The topic often conjures stark images of supporters versus opponents: celebratory wolf reintroductions to Yellowstone National Park and Colorado contrasted with ranchers outraged over lost cattle; pro-wolf protests juxtaposed with wolf bounty hunters. These vivid scenes paint a picture of seemingly irreconcilable division.

But in contrast to these common caricatures, surveys of public opinion consistently show that most people around the world hold positive views of wolves, often overwhelmingly so. This trend holds true even in politically conservative U.S. states, often assumed to be hostile toward wolf conservation. For example, a recent study of ours in Montana found that an increasing majority of residents, 74% in 2023, are tolerant or very tolerant of wolves.

Still, the perception of deep conflict persists and is often amplified by media coverage and politicians. But what if these exaggerated portrayals, and the assumptions of division they reinforce, are themselves contributing to the very conflict they describe? In a study published Jan. 6, 2026, we explored this question.

William F. Campbell/Getty Images

The human side of conservation

We are social scientists who study the human dimensions of environmental issues, from wildfire to wildlife. Using tools from psychology and other social sciences, we examine how people relate to nature and to each other when it comes to environmental issues. These human relationships often matter more to conservation outcomes than the biology of the species or ecosystems in question. Conservation challenges are typically people problems.

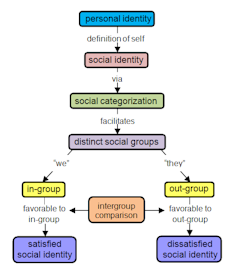

w:en:Jfwang/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

One of the most powerful yet underappreciated forces in these dynamics is social identity, the psychological force that compels people to sort themselves into groups and take those group boundaries seriously. Social identity theory, a foundational concept in psychology, shows that once people see themselves as members of a group, they are naturally inclined to favor “us” and be wary of “them.”

But strong group loyalties also come with costs: They can distort how people see and interpret the world and exacerbate conflict between groups.

When identity distorts reality

Social identity can shape how people interpret even objectively true facts. It can lead people to misjudge physical distances and sizes and assume the worst about members of different groups. When this identification runs deep, a phenomenon called identity fusion can occur, when someone’s personal identity becomes tightly linked to their group identity.

This phenomenon can lead people to act in questionable ways, even ways they might otherwise find immoral, particularly when they believe their group is under threat. For example, it’s possible these forces contribute to high-profile cover-ups of reprehensible behavior.

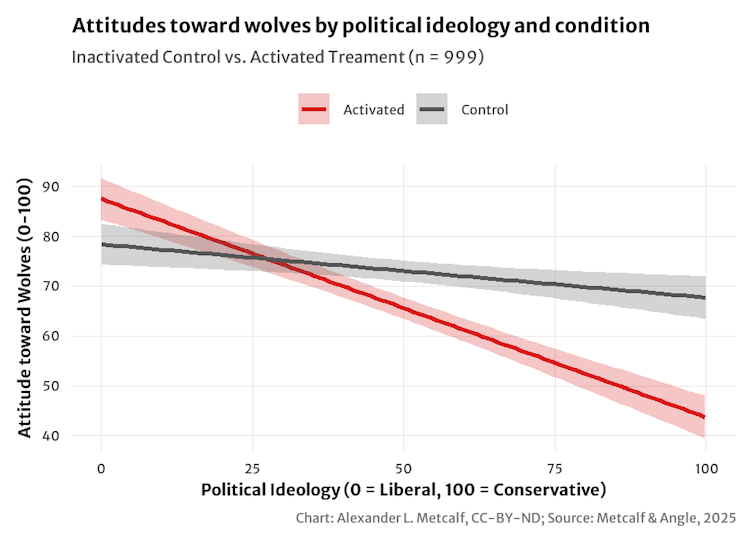

In our recent research, we tested how activating people’s political identities – simply reminding them of their own political party affiliations – affected their perceptions of wolves in the U.S.

Across two studies involving over 2,200 participants from nine states with wolf populations, we found a striking pattern. When we activated people’s political identity, their attitudes toward wolves became more polarized. Democrats’ affinity for wolves increased, as did Republicans’ aversion.

Alexander L. Metcalf

On the other hand, when our particants’ political identities were not activated, they generally liked wolves, regardless of their politics. In a follow-up experiment where we had people guess their fellow and rival party members’ attitudes toward wolves, we found this identity-based polarization was driven by people’s assumptions about their in-group but not their out-group. People incorrectly assumed others in their party held extreme views about wolves, and those assumptions in turn shaped their own attitudes toward the species.

In other words, the caricatures themselves created the conflict.

This is an ironic and tragic outcome: A situation where many people actually agree became polarized not because of deep-seated differences but because of how people imagined others feel.

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife via AP, File

Bridging the gap

Fortunately, the same psychological forces that divide people can also bring them together. When we showed our research participants the actual views of others, specifically that most of their fellow political party members held positive attitudes toward wolves, their own attitudes moderated.

Other strategies for uniting people involve activating “cross-cutting” identities, or shared identities that span traditional divides. For instance, someone might identify both as a rancher and a conservationist, or a hunter who is also a wildlife advocate. More broadly, our respondents are all Americans and community members who share a common humanity. Highlighting these blended and shared identities can reduce the sense of “us vs. them” and open the door to more productive conversations.

The debate over wolves may seem like an intractable clash of values. But our research suggests it doesn’t have to be. When people move beyond caricatures of conflict and recognize the common ground that already exists, we can begin to shift the conversation and maybe even find ways to live not just with wolves, but with each other.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Americans generally like wolves − except when we’re reminded of our politics – https://theconversation.com/americans-generally-like-wolves-except-when-were-reminded-of-our-politics-267511