Source: The Conversation – USA – By Jeff Moersch, Professor of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, University of Tennessee

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

What is below Earth, since space is present in every direction? – Purvi, age 17, India

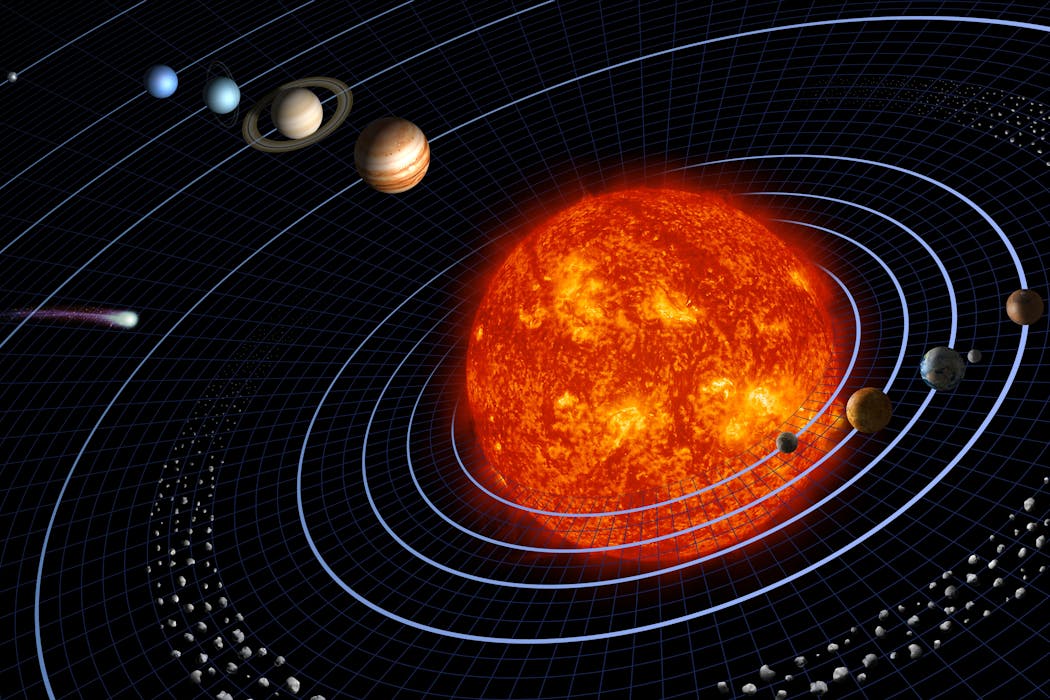

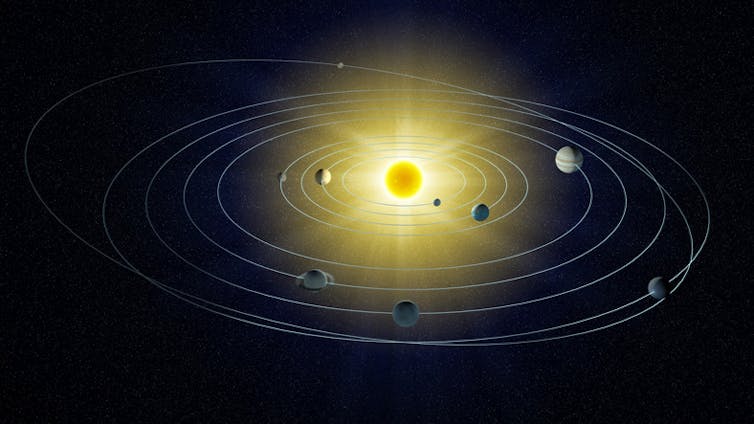

If you’ve seen illustrations or models of the solar system, maybe you noticed that all the planets orbit the Sun in more or less the same plane, traveling in the same direction.

But what is above and below that plane? And why are the planets’ orbits aligned like this, in a flat pancake, rather than each one traveling in a completely different plane?

I’m a planetary scientist who works with robotic spacecraft, such as rovers and orbiters. When my colleagues and I send them out to explore our solar system, it’s important for us to understand the 3D map of our space neighborhood.

Which way is ‘down’?

Earth’s gravity has a lot to do with what people think is up and what is down. Things fall down toward the ground, but that direction depends on where you are.

Imagine you’re standing somewhere in North America and point downward. If you extend a line from your fingertip all the way through the Earth, that line would point in the direction of “up” to someone on a boat in the southern Indian Ocean.

Andrzej Wojcicki/Science Photo Library via Getty Images

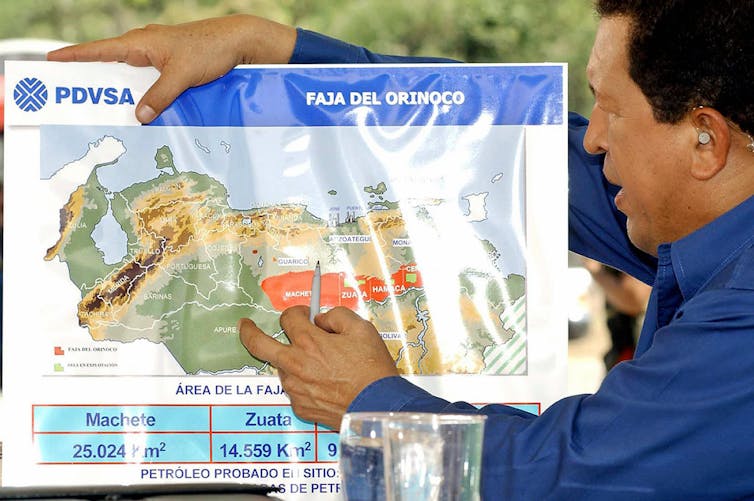

In the bigger picture, “down” could be defined as being below the plane of the solar system, which is known as the ecliptic. By convention, we say that above the plane is where the planets are seen to orbit counterclockwise around the Sun, and from below they are seen to orbit clockwise.

Even more flavors of ‘down’

Is there anything special about the direction of down relative to the ecliptic? To answer that, we need to zoom out even farther. Our solar system is centered on the Sun, which is just one of about 100 billion stars in our galaxy, the Milky Way.

Each of these stars, and their associated planets, are all orbiting around the center of the Milky Way, just like the planets orbit their stars, but on a much longer time scale. And just as the planets in our solar system are not in random orbits, stars in the Milky Way orbit the center of the galaxy close to a plane, which is called the galactic plane.

This plane is not oriented the same way as our solar system’s ecliptic. In fact, the angle between the two planes is about 60 degrees.

NASA Goddard, CC BY

Going another step back, the Milky Way is part of a cluster of galaxies known the the Local Group, and – you can see where this is going – these galaxies mostly fall within another plane, called the supergalactic plane. The supergalactic plane is almost perpendicular to the galactic plane, with an angle between the two planes of about 84.5 degrees.

How these bodies end up traveling paths that are close to the same plane has to do with how they formed in the first place.

Collapse of the solar nebula

The material that would ultimately compose the Sun and the planets of the solar system started out as a diffuse and very extensive cloud of gas and dust called the solar nebula. Every particle within the solar nebula had a tiny amount of mass. Because any mass exerts gravitational force, these particles were attracted to each other, though only very weakly.

The particles in the solar nebula started out moving very slowly. But over a long time, the mutual attraction these particles felt thanks to gravity caused the cloud to start to draw inward on itself, shrinking.

There would have also been some very slight overall rotation to the solar nebula, maybe thanks to the gravitational tug of a passing star. As the cloud collapsed, this rotation would have increased in speed, just like a spinning figure skater spins faster and faster as they draw their arms in toward their body.

As the cloud continued shrinking, the individual particles grew closer to each other and had more and more interactions affecting their motion, both because of gravity and collisions between them. These interactions caused individual particles in orbits that were tilted far from the direction of the overall rotation of the cloud to reorient their orbits.

For example, if a particle coming down through the orbital plane slammed into a particle coming up through that plane, the interaction would tend to cancel out that vertical motion and reorient their orbits into the plane.

Eventually, what was once an amorphous cloud of particles collapsed into a disc shape. Then particles in similar orbits started clumping together, eventually forming the Sun and all the planets that orbit it today.

On much bigger scales, similar sorts of interactions are probably what ended up confining most of the stars that make up the Milky Way into the galactic plane, and most of the galaxies that make up the Local Group into the supergalactic plane.

The orientations of the ecliptic, galactic and supergalactic planes all go back to the initial random rotation direction of the clouds they formed from.

So what’s below the Earth?

So there’s not really anything special about the direction we define as “down” relative to the Earth, other than the fact that there’s not much orbiting the Sun in that direction.

If you go far enough in that direction, you’ll eventually find other stars with their own planetary systems orbiting in completely different orientations. And if you go even farther, you might encounter other galaxies with their own planes of rotation.

This question highlights one of my favorite aspects of astronomy: It puts everything in perspective. If you asked a hundred people on your street, “Which way is down?” every one of them would point in the same direction. But imagine you asked that question of people all over the Earth, or of intelligent life forms in other planetary systems or even other galaxies. They’d all point in different directions.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

![]()

Jeff Moersch receives funding from NASA an the U.S. National Science Foundation.

– ref. What is below Earth, since space is present in every direction? – https://theconversation.com/what-is-below-earth-since-space-is-present-in-every-direction-245348