Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Roxana Shafiee, Environmental Fellow, Center for the Environment, Harvard University; Harvard Kennedy School

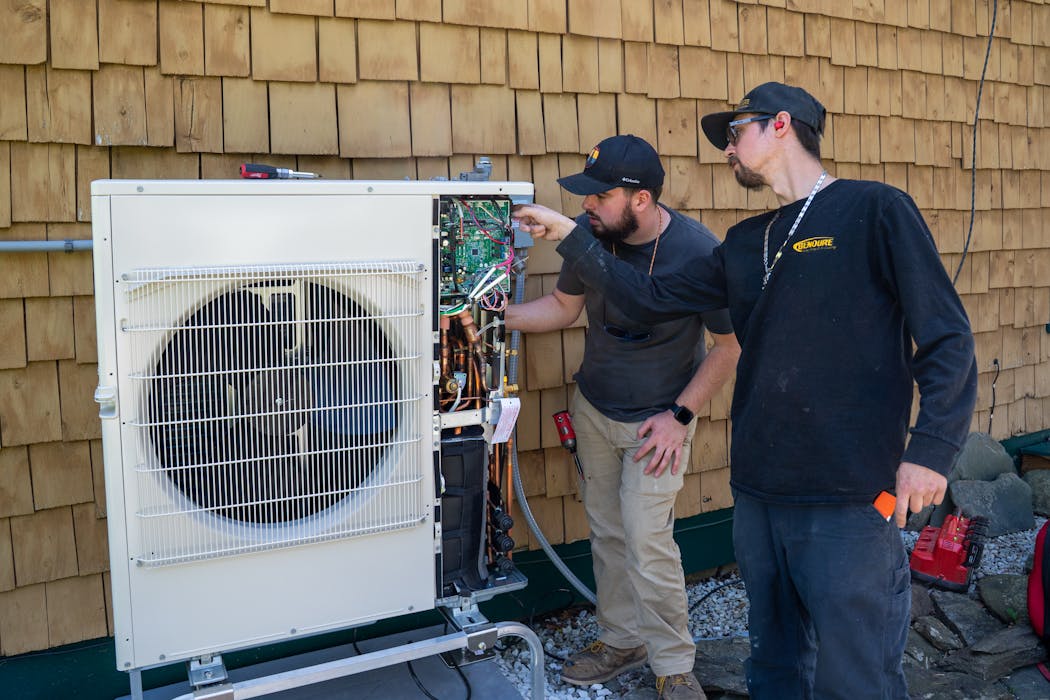

Heat pumps can reduce carbon emissions associated with heating buildings, and many states have set aggressive targets to increase their use in the coming decades. But while heat pumps are often cheaper choices for new buildings, getting homeowners to install them in existing homes isn’t so easy.

Current energy prices, including the rising cost of electricity, mean that homeowners may experience higher heating bills by replacing their current heating systems with heat pumps – at least in some regions of the country.

Heat pumps, which use electricity to move heat from the outside in, are used in only 14% of U.S. households. They are common primarily in warm southern states such as Florida where winter heating needs are relatively low. In the Northeast, where winters are colder and longer, only about 5% of households use a heat pump.

In our new study, my co-author Dan Schrag and I examined how heat pump adoption would change annual heating bills for the average-size household in each county across the U.S. We wanted to understand where heat pumps may already be cost-effective and where other factors may be preventing households from making the switch.

Wide variation in home heating

Across the U.S., people heat their homes with a range of fuels, mainly because of differences in climate, pricing and infrastructure. In colder regions – northern states and states across the Rocky Mountains – most people use natural gas or propane to provide reliable winter heating. In California, most households also use natural gas for heating.

In warmer, southern states, including Florida and Texas, where electricity prices are cheaper, most households use electricity for heating – either in electric furnaces, baseboard resistance heating or to run heat pumps. In the Pacific northwest, where electricity prices are low due to abundant hydropower, electricity is also a dominant heating fuel.

The type of community also affects homes’ fuel choices. Homes in cities are more likely to use natural gas relative to rural areas, where natural gas distribution networks are not as well developed. In rural areas, homes are more likely to use heating oil and propane, which can be stored on property in tanks. Oil is also more commonly used in the Northeast, where properties are older – particularly in New England, where a third of households still rely on oil for heating.

Why heat pumps?

Instead of generating heat by burning fuels such as natural gas that directly emit carbon, heat pumps use electricity to move heat from one place to another. Air-source heat pumps extract the heat of outside air, and ground-source heat pumps, sometimes called geothermal heat pumps, extract heat stored in the ground.

Heat pump efficiency depends on the local climate: A heat pump operated in Florida will provide more heat per unit of electricity used than one in colder northern states such as Minnesota or Massachusetts.

But they are highly efficient: An air-source heat pump can reduce household heating energy use by roughly 30% to 50% relative to existing fossil-based systems and up to 75% relative to inefficient electric systems such as baseboard heaters.

Heat pumps can also reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, although that depends on how their electricity is generated – whether from fossil fuels or cleaner energy, such as wind and solar.

Heat pumps can lower heating bills

We found that for households currently using oil, propane or non-heat pump forms of electric heating – such as electric furnaces or baseboard resistive heaters – installing a heat pump would reduce heating bills across all parts of the country.

The amount a household can save on energy costs with a heat pump depends on region and heating type, averaging between $200 and $500 a year for the average-size household currently using propane or oil.

However, savings can be significantly greater: We found the greatest opportunity for savings in households using inefficient forms of electric heating in northern regions. High electricity prices in the Northeast, for example, mean that heat pumps can save consumers up to $3,000 a year over what they would pay to heat with an electric furnace or to use baseboard heating.

A challenge in converting homes using natural gas

Unfortunately for the households that use natural gas in colder, northern regions – making up around half of the country’s annual heating needs – installing a heat pump could raise their annual heating bills. Our analysis shows that bills could increase by as much as $1,200 per year in northern regions, where electricity costs are as much as five times greater than natural gas per kilowatt-hour.

Even households that install ground-source heat pumps, the most efficient type of heat pump, would still see bill increases in regions with the highest electricity prices relative to natural gas.

Installation costs

In parts of the country where households would see their energy costs drop after installing a heat pump, the savings would eventually offset the upfront costs. But those costs can be significant and discourage people from buying.

On average, it costs $17,000 to install an air-source heat pump and typically at least $30,000 to install a ground-source heat pump.

Some homes may also need upgrades to their electrical systems, which can increase the total installation price even more, by tens of thousands of dollars in some cases, if costly service upgrades are required.

In places where air conditioning is typical, homes may be able to offset some costs by using heat pumps to replace their air conditioning units as well as their heating systems. For instance, a new program in California aims to encourage homeowners who are installing central air conditioning or replacing broken AC systems to get energy-efficient heat pumps that provide both heating and cooling.

Rising costs of electricity

A main finding of our analysis was that the cost of electricity is key to encouraging people to install heat pumps.

Electricity prices have risen sharply across the U.S. in recent years, driven by factors such as extreme weather, aging infrastructure and increasing demand for electric power. New data center demand has added further pressure and raised questions about who bears these costs.

Heat pump installations will also increase electricity demand on the grid: The full electrification of home heating across the country would increase peak electricity demand by about 70%. But heat pumps – when used in concert with other technologies such as hot-water storage – can provide opportunities for grid balancing and be paired with discounted or time-of-use rate structures to reduce overall operating costs. In some states, regulators have ordered utilities to discount electricity costs for homes that use heat pumps.

But ultimately, encouraging households to embrace heat pumps and broader economy-wide electrification, including electric vehicles, will require more than just technological fixes and a lot more electricity – it will require lower power prices.

![]()

Roxana Shafiee does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Americans want heat pumps – but high electricity prices may get in the way – https://theconversation.com/americans-want-heat-pumps-but-high-electricity-prices-may-get-in-the-way-273981