Source: The Conversation – Canada – By James Deaville, Professor of Music, Carleton University

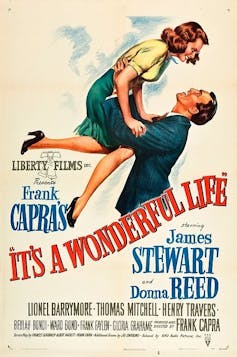

Hailed by many critics and movie lovers as a “timeless classic” — and ranking first on the American Film Institute’s list of the 100 most inspiring films of all time — It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) has found a secure place in the hearts of audiences.

(Wikimedia Commons)

The story revolves around George Bailey, who sacrifices his personal dreams to support the small community of Bedford Falls. When a financial crisis pushes him to the brink of despair, an angel intervenes and reveals what the town’s life would look like had George never been born.

George is confronted with an alternative reality in what the film frames as a foil city, Pottersville. There, he rediscovers the value of his contributions and returns to Bedford Falls renewed, to what some viewers regard as an outpouring of communal generosity and small-town virtue.

Yet part of the film’s appeal can be attributed to its existential themes about the meaning of life.

The movie’s soundtrack — including contributions by Hollywood composer Dimitri Tiomkin — plays a central role in It’s a Wonderful Life, underscoring problems and tensions beneath the surface. Some depictions of music and sound beg analysis around how these reflect racist ideas about “proper” musical, social and community norms.

Film origins

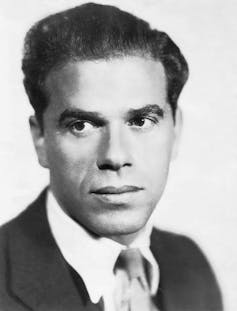

The film began its life as a short story called The Greatest Gift (1939). Film studio RKO bought the story in 1944 and sold it to director Frank Capra’s new company, Liberty Films, in 1945.

(Wikimedia Commons)

A team of writers — including Capra himself — rewrote the script and set to work on getting Jimmy Stewart, earlier cast in two of Capra’s pre-war films, to star.

Just back from serving in the Second World War, Stewart was reluctant, not least because of what was then known as shellshock and is now called post-traumatic stress disorder from his wartime experiences. Capra successfully coaxed Stewart into taking the role.

It’s a Wonderful Life was intended for release in January 1947, but the studio moved up the premiere to Dec. 20 in order to qualify for the 1946 Academy Awards.

The film’s success came after early scrutiny. An FBI agent attended an early screening and found the film undermined the institution of banking and advanced notions of a demoralized public, but the bureau decided not to pursue prosecution.

The fact that the film was neither a financial nor a critical success upon release is well known.

Less often acknowledged is that, owing to a clerical failure to file the necessary copyright renewal, the film slipped into the public domain, ensuring decades of holiday broadcasts that ultimately recast it as a Christmas icon.

Musical score

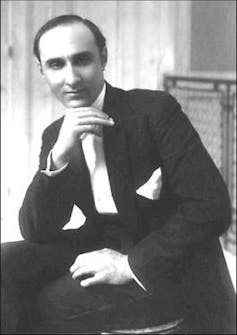

(Wikimedia Commons)

Tiomkin had already worked with Capra on several film projects, including Lost Horizon (1937) and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), as well as providing music for the director’s Why We Fight series (1942-1945).

Capra’s selection of Tiomkin for It’s a Wonderful Life is not surprising, yet little of his score remains in the final film.

Tiomkin had composed a full set of cues, which the movie condenses to about 25-30 minutes in a 130-minute run time. Tiomkin’s original cues bear such titles as “Death Telegram” and “George Is Unborn,” and are available on a 2014 recording consisting of 28 tracks.

Memorable musical moments

However, the most memorable musical moments in the film aren’t Tiomkin’s. Instead, they involve citations of well-known traditional and holiday favourites including Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star, Auld Lang Syne, Silent Night, Adeste Fidelis as well as the folk song Buffalo Gals,“ arranged by Tiomkin, and the popular jazz composition, The Charleston by James P. Johnson.

The film score emerges as choppy and highly varied, not only because of Capra’s cuts, but also by his tracking in cues from other movies. Alfred Newman’s Hallelujah from the Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939) is heard as George jubilantly runs down the main street of Bedford Falls.

The Gregorian chant “Dies Irae” from the 13th century Mass for the Dead is heard when George — on the bridge — changes his mind about dying.

Tiomkin never worked with Capra again.

Race, music and community

A key concerning aspect to the music heard in It’s a Wonderful Life revolves around the portrayal of Black musical forms and practitioners.

Capra’s known racism against Blacks, consistent with racist discourses and practices of the era, is reflected in how jazz and other Black musical forms appear and are framed.

In the iconic Bedford falls dance, the band plays three songs, including

African American pianist and composer Johnson’s “Charleston,” which is performed by a white band.

As American journalism professor Sam Freedman notes in a podcast on whiteness and racism in America, the town features predominantly white citizens apart from a stereotypical depiction of a Black housekeeper in the Bailey family.

Read more:

I am not your nice ‘Mammy’: How racist stereotypes still impact women

The sounds of Pottersville

Music is essential to how the dystopian town, Pottersville, is imagined during George’s manic episode.

There, Black jazz reigns supreme, symbolized by the onscreen performance of unrecognizable music by Meade Lux Lewis, a pioneering and acclaimed composer and boogie woogie pianist.

In the uncredited performance, Lewis is at the keyboard wearing a derby and smoking a stogie. He appears in Nick’s Bar, which the screenwriters describe as “a hard-drinking joint, a honky-tonk … People are lower down and tougher.”

Outside the bar, we hear the fragmented strains of jazz from the dive bar pouring into the town’s main street.

Outside the bar, George bumps into Bedford Falls characters who are, in this alternate setting, destitute and desperate. The quaint main street is overrun by nightclubs and full of bright lights. Through Pottersville, the film projects a sense of moral degradation.

While negatively portraying jazz practised by Black artists, the film simultaneously draws upon and appropriates Black musical forms as necessary and key to popular American life but in a white-controlled version.

Not-so-idyllic Bedford Falls

Despite Capra’s attempt at a happy ending, in the not-so-idyllic Bedford Falls, George is not fully aware of the malicious meddling of a rich, white citizen of Bedford — Henry F. Potter — which catalyzed his financial problems.

Read more:

The dystopian Pottersville in ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ is starting to feel less like fiction

George awakens from his Pottersville reverie to re-commit to small-town life. While some viewers see the ending as affirming community, the film also keeps George partly ignorant of how the forces of inequity are actually operating in his largely white community.

Maybe we can appreciate the film on a deeper level, when we consider its varied and competing narratives around music, race, class and belonging.

![]()

James Deaville receives funding from SSHRC.

– ref. It’s a Wonderful Life: A Christmas classic that reflects bigoted ideas about ‘proper’ music in the 1940s – https://theconversation.com/its-a-wonderful-life-a-christmas-classic-that-reflects-bigoted-ideas-about-proper-music-in-the-1940s-270740