Source: The Conversation – in French – By Cavan W. Concannon, Professor of Religion and Classics, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Derrière la fête de la Saint-Sylvestre se cache une histoire de pouvoir : celle d’un christianisme qui, au IVᵉ siècle, invente les récits et les traditions destinés à légitimer son alliance avec l’État.

Le 31 décembre, tandis que la majorité d’entre nous se préparent à célébrer le réveillon du Nouvel An, quelques catholiques commémorent également la fête de saint Sylvestre.

On sait peu de choses avec certitude sur la vie de Sylvestre, mais il a vécu à une période charnière de l’histoire du christianisme. De 314 à 335 de notre ère, Sylvestre fut l’évêque de Rome, ce que l’on appelle aujourd’hui le pape, même si la fonction n’avait alors pas le pouvoir qu’elle exercera par la suite. Le mot « pape » vient du grec signifiant « père » et était largement utilisé par les évêques jusqu’au Ve siècle, lorsque l’évêque de Rome a commencé à en monopoliser l’usage.

L’époque de Sylvestre est à la fois marquée par les troubles et par une profonde transition pour les chrétiens de l’Empire, alors que des communautés chrétiennes sortent des persécutions pour nouer une alliance puissante avec l’État romain. Son histoire est étroitement liée à cette alliance, qui allait transformer en profondeur la trajectoire du mouvement initié trois siècles plus tôt par la figure de Jésus. Le christianisme devient alors la religion des rois, des États et des empires.

Un changement de destin

Les informations fiables sur la vie de Sylvestre sont rares. Le « Liber Pontificalis », un recueil de biographies pontificales commencé au VIᵉ siècle, indique qu’il était originaire de Rome et fils d’un homme par ailleurs inconnu nommé Rufinus.

Jeune homme, Sylvestre a connu les persécutions lancées sous l’un des coempereurs de l’époque, Dioclétien, à partir de 303 de notre ère. Ces persécutions se sont poursuivies plusieurs années après l’abdication de Dioclétien.

Si l’on imagine volontiers les premiers chrétiens constamment persécutés par l’État romain, les historiens nuancent cette vision. Mais les persécutions entamées sous Dioclétien, elles, font figure d’exception. À cette époque, l’État exigeait des chrétiens qu’ils sacrifient aux dieux pour le bien de l’Empire, sous peine de sanctions — parfois violentes.

Titus Project via Wikimedia Commons

Selon le théologien chrétien Augustin, certains chrétiens ont par la suite accusé Sylvestre d’avoir « trahi » sa foi durant cette période. Il lui était reproché d’avoir remis aux autorités romaines des livres sacrés chrétiens et d’avoir fait des offrandes aux dieux romains.

Les persécutions prennent fin en 313, lorsque les coempereurs Constantin et Licinius signent l’édit de Milan, qui accorde une forme de tolérance au christianisme dans l’Empire. Un an plus tard à peine, Sylvestre devient évêque de Rome. Constantin s’impose rapidement comme un grand protecteur des chrétiens, même si l’ampleur de sa pratique personnelle du christianisme fait débat. Avec le soutien impérial s’ouvre à Rome une vaste campagne de constructions chrétiennes, à tel point que l’essentiel de la biographie de Sylvestre dans le « Liber Pontificalis » se résume à l’énumération des églises que Constantin a offertes à la ville.

Controverses chrétiennes

Avant comme pendant l’épiscopat de Sylvestre à Rome, il existait dans l’Empire de nombreuses formes de christianisme. Cette diversité inquiétait Constantin, soucieux de promouvoir l’unité et l’ordre au sein de ses territoires. Il entreprend donc de réunir des conciles de clercs chrétiens afin de trancher les questions les plus controversées.

En 314, l’année même où Sylvestre devient évêque, l’empereur convoque le concile d’Arles pour régler un conflit apparu parmi les évêques africains — ce que l’on appelle la controverse donatiste. La question centrale était de savoir si un prêtre ayant trahi sa foi lors des persécutions conservait une ordination valide.

Jjensen/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Une dizaine d’années plus tard, peu après que Constantin est devenu l’unique dirigeant du monde romain, il convoqua un autre concile à Nicée, dans l’actuelle Turquie. Cette fois, il souhaitait que les responsables chrétiens s’attaquent à une fracture émergente centrée sur l’activité d’un clerc charismatique nommé Arius. Sylvestre n’assista pas non plus à ce concile, mais envoya là encore des représentants.

Le concile adopta finalement ce que l’on a appelé le Credo de Nicée, une profession de foi qui demeure importante pour de nombreux chrétiens aujourd’hui. Toutefois, le concile ne résolut pas la division autour d’Arius. En réalité, Constantin sera plus tard baptisé par un partisan d’Arius, Eusèbe de Nicomédie.

Les décennies durant lesquelles Sylvestre présida l’Église transformèrent le christianisme : d’un groupe persécuté, il devint un allié de l’État. Cette alliance rendit les divergences théologiques entre chrétiens encore plus explosives, puisque la force de l’Empire pouvait désormais être mobilisée contre ses adversaires.

Réécrire l’histoire

Mais pourquoi, malgré ces bouleversements majeurs, Sylvestre n’a-t-il pas été considéré comme un acteur central de la vie politique de son temps ?

C’est une question qui a hanté les chrétiens des générations suivantes — au point qu’ils ont inventé des récits plaçant Sylvestre au cœur même des événements.

Au Ve siècle, un auteur anonyme rédigea une biographie connue aujourd’hui sous le nom des « Actes de Sylvestre », qui le présentait comme une figure centrale de la conversion de Constantin au christianisme.

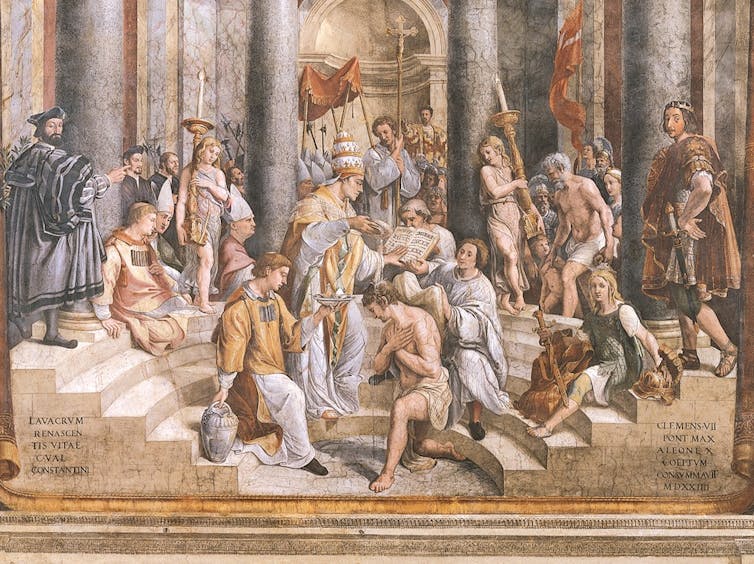

Dans les Actes, Constantin apparaît d’abord comme un persécuteur des chrétiens, acte pour lequel Dieu le frappe de la lèpre. Sylvestre, qui vivait en exil sur une montagne près de Rome en raison de ces persécutions, est rappelé dans la ville après que les saints Pierre et Paul rendent visite à Constantin en rêve. Sylvestre recueille alors la confession de foi de Constantin, le guérit miraculeusement de sa lèpre, puis baptise l’empereur. Ainsi, ce dernier recevait enfin un baptême en bonne et due forme de la part d’un évêque orthodoxe, et non d’un hérétique arien.

Musées du Vatican via Wikimedia Commons

Un siècle plus tard, le « Liber Pontificalis » affirme que c’était Sylvestre, et non Constantin, qui avait convoqué les conciles d’Arles et de Nicée. Le texte lui attribue également une série de décisions juridiques. Ces réécritures du récit autour de Sylvestre l’élevaient au rang d’acteur majeur des événements de son époque. Elles soutenaient aussi un effort croissant visant à doter l’évêque de Rome d’un type d’autorité comparable à celle qu’exercent les papes modernes.

Donations et dragons

Avec le temps, les légendes autour de Sylvestre n’ont fait que s’amplifier — au point d’inclure un combat contre un dragon démoniaque. Mais l’héritage le plus célèbre, et le plus controversé, associé à Sylvestre est sans doute lié à la prétendue « Donation de Constantin ».

Ce document falsifié a été rédigé pour la première fois au VIIIe siècle de notre ère. La Donation affirme que l’empereur Constantin aurait légué à l’évêque de Rome — en l’occurrence Sylvestre — le contrôle de la ville de Rome, de l’Empire romain d’Occident, d’immenses territoires relevant de l’autorité impériale, ainsi qu’une autorité sur les Églises des autres grands centres du monde chrétien, dont Constantinople.

Pendant des siècles, ce document a servi de fondement aux revendications pontificales en matière de pouvoir à la fois ecclésiastique et civil. Au XVe siècle, le cardinal allemand Nicolas de Cues et l’érudit italien Lorenzo Valla démontrèrent que la Donation était un faux, mais à ce stade les papes avaient déjà accumulé l’autorité et la richesse désormais associées à la fonction.

Peter1936F/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Même si les détails précis de la vie de Sylvestre resteront sans doute à jamais mystérieux, l’époque dans laquelle il a vécu a été décisive pour l’histoire du christianisme et de l’Occident. Durant son épiscopat, le christianisme a fait ses premiers pas vers une alliance durable avec le pouvoir impérial et étatique. Avec le temps, le récit de Sylvestre a été enrichi, non seulement pour justifier cette alliance, mais aussi pour soutenir l’idée que l’Église devait exercer un pouvoir politique.

Aujourd’hui, un bloc influent de nationalistes chrétiens aux États-Unis cherche un pouvoir similaire. Pour certains, l’inspiration de ce projet politique repose sur l’idée d’une alliance naturelle entre l’Église et l’État — qui commencerait avec Constantin, mais elle cherche sa justification dans des traditions inventées autour de la vie de Sylvestre. Or cette alliance fut un accident de l’histoire, et non une fatalité. Avec le temps, les chrétiens de l’Empire romain ont élaboré des justifications expliquant pourquoi l’Église devait s’aligner sur l’État — puis, à terme, devenir l’État.

![]()

Cavan W. Concannon ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. Le pape discret devenu légende : qui était vraiment saint Sylvestre, fêté le 31 décembre ? – https://theconversation.com/le-pape-discret-devenu-legende-qui-etait-vraiment-saint-sylvestre-fete-le-31-decembre-271674