Source: The Conversation – France (in French) – By Marshall, A., Visiting professor, Mahidol University

Alfred Russel Wallace was a British naturalist renowned for co-developing the theory of evolution alongside Charles Darwin – and for mapping out the biodiversity of the Indonesian Archipelago. However, his legacy extends far beyond science.

Wallace’s observations of social exploitation in Wales and the Archipelago compelled him to take a stand against the British establishment in his homeland and its colonial ventures abroad. He also recognised the ecological destruction caused by colonialism, making him one of the world’s first global environmentalists.

In the 19th century, Wallace’s observations were striking. British imperialism was at its zenith, and the Industrial Revolution was fueling a titanic amplification of human impact upon nature.

Wallace’s observations are probably even more noteworthy today. While European colonialism has largely collapsed, the world is industrialising at breakneck speed, intensifying the environmental damage Wallace warned about.

Witness to poverty: Wales

Wallace was born in 1823, and his early life in Wales exposed him to 19th-century rural struggles.

Historians have noted that Wales was one of the first regions to suffer English colonisation, dating back to medieval times.

By Wallace’s time, industrialisation had reshaped the Welsh landscape, with factories, mines, and railways supplanting its pristine mountains and valleys. While displaced farmers found work in these industries, the jobs were poorly paid, perilous, and often dehumanising. Wallace saw the ongoing struggle of Welsh communities to protect their farming rights and preserve their language.

Young Wallace initially worked as a mapmaker. His employers were usually wealthy landlords who hired him to map their estates to determine how much their tenant farmers owed them in rent or taxes.

At work, he witnessed how British landlords in Wales were becoming ‘more commercially minded’ (in other words, more money-grubbing). They often evicted impoverished tenant farmers to make way for profitable livestock, or mining and railway projects. If they weren’t pushed off the land altogether, the tenants faced rising rents and heavier taxes. Whatever the situation, it was usually the tenant farmers who were distressed.

Wallace was sometimes sent to collect rent and taxes from tenants, many of whom lived in poverty and barely spoke English to understand the circumstances they were in.

Wallace felt anguished for being part of the wretched business.

Eventually, after the private estates in Wales were just about entirely mapped, he decided to leave his career as a mapmaker.

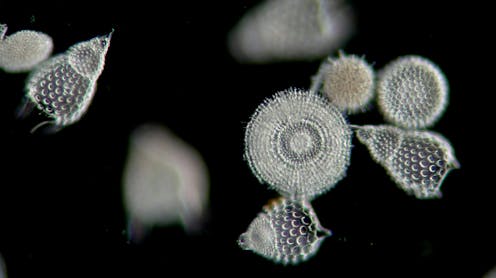

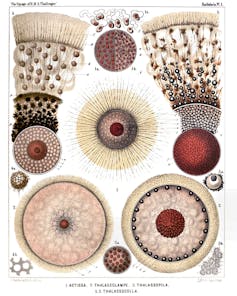

At this point, Wallace became a full-time naturalist, collecting insect specimens and selling them to museums.

This new role led him to travel all across the world – including to the Indonesian Archipelago – where he spent eight years immersing himself in local cultures and languages such as Malay.

Sympathy for the colonised: The Archipelago

Initially, Wallace perceived Dutch colonialism as less exploitative than British practices. For the most part, this was because Wallace was comparing the state-run enterprises that dominated the economy of the Dutch East Indies with the avaricious companies that dominated the economies of British India and British Malaya. This preference for state capitalism versus laissez-faire capitalism even led Wallace to sympathise with the Cultivation System (Cultuurstelsel) imposed by the Dutch government.

Under this system, local farmers grew cash crops for the Dutch East Indies government. In exchange, they received some small payments below the market rate.

Wallace acknowledged that Dutch middlemen and local chiefs sometimes abused the system, but it often provided the growers with a reliable income. As well, the Dutch overlords were often obliged to build infrastructure and schools.

The system was criticised as a form of monopolistic serfdom. But Wallace saw it as less brutal than the ‘dog-eat-dog’ economies of Britain’s overseas free-trade colonies.

However, his perspective evolved. In later writings, Wallace rallied against the premise that any nation in the tropics need be colonised. He also realised colonised peoples didn’t gain much from the deal, if ‘deal’ we might call it.

In his 1898 book summarising human achievement in the 19th century, Wallace declared that the worst aspect of the century was the way Europeans mistreated native peoples worldwide.

Wallace noted that colonised lands worldwide were usually gained in dubious manners, and various abusive labour practices maintained their economies. By the turn of the century, Wallace was calling for all colonies to be handed back to indigenous peoples.

At the same time, in his homeland, Wallace also became a leading figure in the land nationalisation movement. In an effort to address rural poverty in Britain, Wallace advocated the nationalisation of all farmlands.

Entrusted to the state, farming rights could then be distributed fairly and democratically among the entire national community of farmers. In this manner, every farming family could grow their own food, either for themselves or to sell, without being impoverished by taxes and rents claimed by the gentry.

Destruction of nature

As a naturalist deeply connected to the environment, Wallace also documented colonial ventures disastrous impact on wildlife. When European ventures established estates in the tropics, the native rainforests were swiftly cleared.

In his own words:

The reckless destruction of forests, which have for ages been the protection and sustenance of the inhabitants, seems to me to be one of the most shortsighted acts of colonial mismanagement—Wallace in The Malay Archipelago.

Wallace also condemned the environmental impact of colonial mining in the Archipelago, especially those targeting gold and tin, which he witnessed in Borneo and the Malay Peninsula:

The rapid degradation of fertile valleys and the poisoning of streams by mining waste serve as stark reminders of the greed of commerce unchecked by reason or compassion—Wallace in The Malay Archipelago.

These observations, penned in the late 19th century, clearly anticipated 21st-century environmental problems and their causes.

Wallace’s foresight was rare at his time, and his warning was even more striking. He believed that nature’s destruction could only be avoided by taking much more equitable approaches to resource use.

Life lessons

Modern historians and scientists hail Wallace as one of the bravest figures of the 19th century. He possessed enough physical courage to cross vast oceans and live for years away from home in remote, untamed forests. This courage allowed Wallace to explore the natural world deeply enough to uncover its hidden forces.

Equally impressive was Wallace’s moral courage. At a time when criticising the British elite or questioning imperialism was far from popular, Wallace did not shy away from challenging the status quo. Many of his books envision a better, fairer world.

Wallace’s moral courage is something we can all learn from today, especially as we realise that scientific knowledge alone is not enough to protect nature from relentless industrialisation.

![]()

Marshall, A. tidak bekerja, menjadi konsultan, memiliki saham, atau menerima dana dari perusahaan atau organisasi mana pun yang akan mengambil untung dari artikel ini, dan telah mengungkapkan bahwa ia tidak memiliki afiliasi selain yang telah disebut di atas.

– ref. Beyond Evolution: Alfred Russel Wallace’s critique of the 19th century world – https://theconversation.com/beyond-evolution-alfred-russel-wallaces-critique-of-the-19th-century-world-243372