Source: – By Gwenaël Leblong-Masclet, Chaire Mers, Maritimités et Maritimisations du Monde (4M), Sciences Po Rennes

La 3ᵉ Conférence des Nations unies sur l’océan (Unoc 3) se tient à Nice à partir du 9 juin 2025. Elle met notamment en lumière un enjeu souvent sous-estimé : la place stratégique des collectivités territoriales dans la gouvernance maritime. Étude de cas à Lacanau en Aquitaine, au Parc naturel marin d’Iroise en Bretagne et au Parlement de la mer en Occitanie.

L’océan, théâtre des bouleversements de l’anthropocène, n’est pas une abstraction lointaine. Pour les territoires littoraux, il est une réalité concrète, quotidienne, faite de défis de submersion, d’érosion, d’aménagement, de développement portuaire ou encore d’adaptation des politiques touristiques. C’est depuis ces territoires que la préservation des océans peut – et doit – être repensée.

Dans un prochain article « Les politiques publiques locales au prisme de la maritimité » dans la revue Pouvoirs locaux, nous nous sommes demandé si, plutôt que de voir la mer comme un obstacle, nous la considérions comme un levier de transformation de l’action publique ?

Les élus au chevet du trait de côte

Les élus locaux sont les premiers à affronter les conséquences visibles du changement climatique : tempêtes plus fréquentes, recul du trait de côte, érosion accélérée. La compétence de gestion des milieux aquatiques et prévention des inondations (Gemapi), confiée aux intercommunalités, les placent en première ligne.

À Lacanau, des projets de désurbanisation volontaire ont été lancés pour anticiper le recul du littoral, en concertation avec les habitants et les acteurs économiques. Au programme : suppression des parkings littoraux, aménagement d’un pôle d’échange multimodal plus à l’intérieur des terres, repositionnement des missions de secours ou encore le déplacement de certains commerces situés sur le front de mer.

Ce processus implique des arbitrages difficiles entre maintiens des activités touristiques, relocalisation des infrastructures, préservation des écosystèmes et accompagnement des habitants concernés. La loi Climat et résilience de 2021 a introduit des outils juridiques pour anticiper ce recul. Leur mise en œuvre concrète reste à parfaire. Sans action locale forte et coordonnée, les effets du changement climatique sur le littoral risquent d’être incontrôlables et, surtout, d’être une nouvelle source d’inégalités humaines et territoriales.

Gouverner un espace fragile

Si l’océan couvre 70 % de la planète, son interface avec la terre – le littoral – est l’un des espaces les plus disputés et les plus fragiles. Y coexistent des usages parfois antagonistes : tourisme, conchyliculture, urbanisation, activités portuaires, pêche, énergies marines renouvelables (EMR)… Cette multiplicité appelle une gouvernance intégrée, à la fois verticale – de l’échelon local à l’échelon international – et horizontale – entre acteurs publics, privés et citoyens.

Elle implique de penser une gouvernance écosystémique des littoraux, s’appuyant sur :

- des mécaniques démocratiques multiscalaires (à plusieurs échelles),

- les savoirs empiriques des communautés locales comme les pêcheurs,

- les parties prenantes économiques.

Aux collectivités, mises en situation d’agir par la gestion intégrée des zones côtières ou par les documents stratégiques de façade, de savoir créer les espaces de négociation et de consensus entre ces acteurs.

Certaines collectivités ont déjà innové. En Bretagne, le Parc naturel marin d’Iroise a été conçu avec les pêcheurs locaux et les associations environnementales, permettant une cogestion efficace.

L’exemple de la Région Occitanie, avec son Parlement de la mer, lancé dès 2013, montre que les collectivités peuvent innover en matière de gouvernance maritime. Ce parlement régional fédère élus, professionnels, ONG et chercheurs pour co-construire une stratégie maritime partagée.

À Brest, la métropole a su capitaliser sur sa fonction portuaire et scientifique pour faire émerger une véritable « capitale des océans », mobilisant universités, centres de recherche, industriels et autorités portuaires autour d’une même ambition.

Laboratoire maritime… d’innovation territoriale

Acteurs traditionnellement davantage « terriens » que maritimes, les collectivités territoriales revendiquent aujourd’hui une place à la table des négociations sur les politiques océaniques.

À rebours d’une vision exclusivement étatique, les élus locaux portent une connaissance fine des dynamiques littorales, des conflits d’usages et des attentes citoyennes. Ces démarches incitent à penser la mer comme bien commun.

L’un des apports essentiels de la conférence Unoc 3 sera, du moins peut-on l’espérer, de rappeler que la protection des océans ne peut se faire sans la reconnaissance de l’ensemble des acteurs territoriaux.

Du lundi au vendredi + le dimanche, recevez gratuitement les analyses et décryptages de nos experts pour un autre regard sur l’actualité. Abonnez-vous dès aujourd’hui !

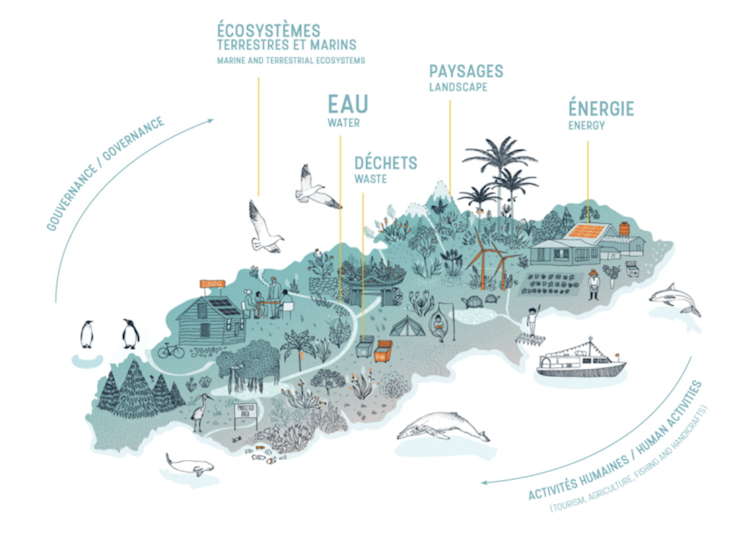

La mobilisation des territoires insulaires, par exemple au sein de l’ONG Smilo, contribue à une reconnaissance du rôle des initiatives locales comme levier de changement. L’insularité est le « laboratoire » d’un développement durable et concerté des stratégies territoriales.

Le développement des aires marines protégées (AMP) en est une bonne illustration : leur efficacité dépend en grande partie de l’implication des communautés locales, des pêcheurs, des associations. À ce titre, intégrer les savoirs empiriques dans les politiques de gestion maritime n’est pas un luxe, mais une nécessité. Ainsi, le rahui polynésien – interdiction temporaire d’exploitation d’une zone pour permettre sa régénération – inspire désormais les pratiques de préservation de la ressource halieutique, bien au-delà du seul triangle polynésien.

Fourni par l’auteur

Plus globalement, l’insularité, problématique récurrente dans les Outre-mer, implique de penser et d’accepter la différenciation des politiques publiques. Les élus d’Ouessant, de Mayotte ou des Marquises rappellent que les contraintes logistiques, la dépendance à la mer et la fragilité des écosystèmes appellent des réponses sur mesure, souvent loin des seuls standards gouvernementaux.

Penser global, agir local

Observer les politiques locales depuis le large permet d’inverser le regard. Le littoral, espace de contact entre l’humain et le vivant, devient alors un laboratoire d’innovation démocratique, écologique et institutionnelle, où se dessinent des formes renouvelées de coopération et d’engagement. L’Unoc 3 offre une occasion décisive de rappeler que la transition maritime ne se fera pas sans les territoires.

Il est donc temps de reconnaître pleinement le rôle des élus locaux dans cette dynamique. Ils sont les chevilles ouvrières d’une action publique renouvelée, plus proche du terrain, plus attentive aux équilibres écosystémiques et plus sensible aux savoirs citoyens.

Parce que la mer est ici – sur les plages, dans les ports, dans les écoles et les projets municipaux –, elle engage la responsabilité de tous, à commencer par celles et ceux qui construisent au quotidien les politiques publiques locales.

![]()

Je suis DGA de Brest métropole.

Romain Pasquier ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. L’océan est aussi l’affaire des élus locaux : exemples en Aquitaine, en Bretagne et en Occitanie – https://theconversation.com/locean-est-aussi-laffaire-des-elus-locaux-exemples-en-aquitaine-en-bretagne-et-en-occitanie-257592