Source: The Conversation – USA – By James F. Holden, Professor of Microbiology, UMass Amherst

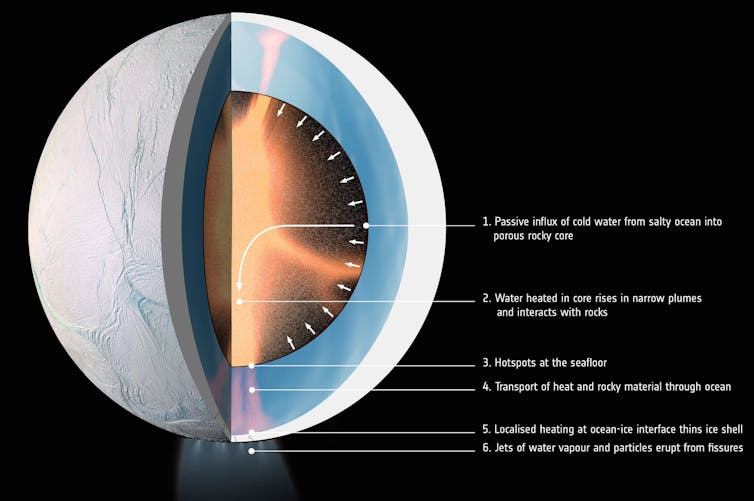

People have long wondered what life was first like on Earth, and if there is life in our solar system beyond our planet. Scientists have reason to believe that some of the moons in our solar system – like Jupiter’s Europa and Saturn’s Enceladus – may contain deep, salty liquid oceans under an icy shell. Seafloor volcanoes could heat these moons’ oceans and provide the basic chemicals needed for life.

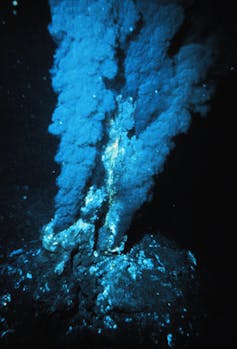

Similar deep-sea volcanoes found on Earth support microbial life that lives inside solid rock without sunlight and oxygen. Some of these microbes, called thermophiles, live at temperatures hot enough to boil water on the surface. They grow from the chemicals coming out of active volcanoes.

Because these microorganisms existed before there was photosynthesis or oxygen on Earth, scientists think these deep-sea volcanoes and microbes could resemble the earliest habitats and life on Earth, and beyond.

To determine if life could exist beyond Earth in these ocean worlds, NASA sent the Cassini spacecraft to orbit Saturn in 1997. The agency has also sent three spacecraft to orbit Jupiter: Galileo in 1989, Juno in 2011 and most recently Europa Clipper in 2024. These spacecraft flew and will fly close to Enceladus and Europa to measure their habitability for life using a suite of instruments.

Surface: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute; interior: LPG-CNRS/U. Nantes/U. Angers. Graphic composition: ESA

However, for planetary scientists to interpret the data they collect, they need to first understand how similar habitats function and host life on Earth.

My microbiology laboratory at the University of Massachusetts Amherst studies thermophiles from hot springs at deep-sea volcanoes, also called hydrothermal vents.

Diving deep for samples of life

I grew up in Spokane, Washington, and had over an inch of volcanic ash land on my home when Mount St. Helens erupted in 1980. That event led to my fascination with volcanoes.

Several years later, while studying oceanography in college, I collected samples from Mount St. Helens’ hot springs and studied a thermophile from the site. I later collected samples at hydrothermal vents along an undersea volcanic mountain range hundreds of miles off the coast of Washington and Oregon. I have continued to study these hydrothermal vents and their microbes for nearly four decades.

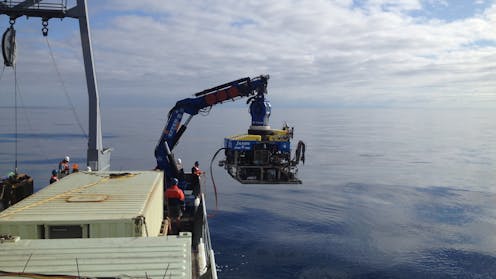

Gavin Eppard, WHOI/Expedition to the Deep Slope/NOAA/OER, CC BY

Submarine pilots collect the samples my team uses from hydrothermal vents using human-occupied submarines or remotely operated submersibles. These vehicles are lowered into the ocean from research ships where scientists conduct research 24 hours a day, often for weeks at a time.

The samples collected include rocks and heated hydrothermal fluids that rise from cracks in the seafloor.

The submarines use mechanical arms to collect the rocks and special sampling pumps and bags to collect the hydrothermal fluids. The submarines usually remain on the seafloor for about a day before returning samples to the surface. They make multiple trips to the seafloor on each expedition.

Inside the solid rock of the seafloor, hydrothermal fluids as hot at 662 degrees Fahrenheit (350 Celsius) mix with cold seawater in cracks and pores of the rock. The mixture of hydrothermal fluid and seawater creates the ideal temperatures and chemical conditions that thermophiles need to live and grow.

P. Rona / OAR/National Undersea Research Program; NOAA

When the submarines return to the ship, scientists – including my research team – begin analyzing the chemistry, minerals and organic material like DNA in the collected water and rock samples.

These samples contain live microbes that we can cultivate, so we grow the microbes we are interested in studying while on the ship. The samples provide a snapshot of how microbes live and grow in their natural environment.

Thermophiles in the lab

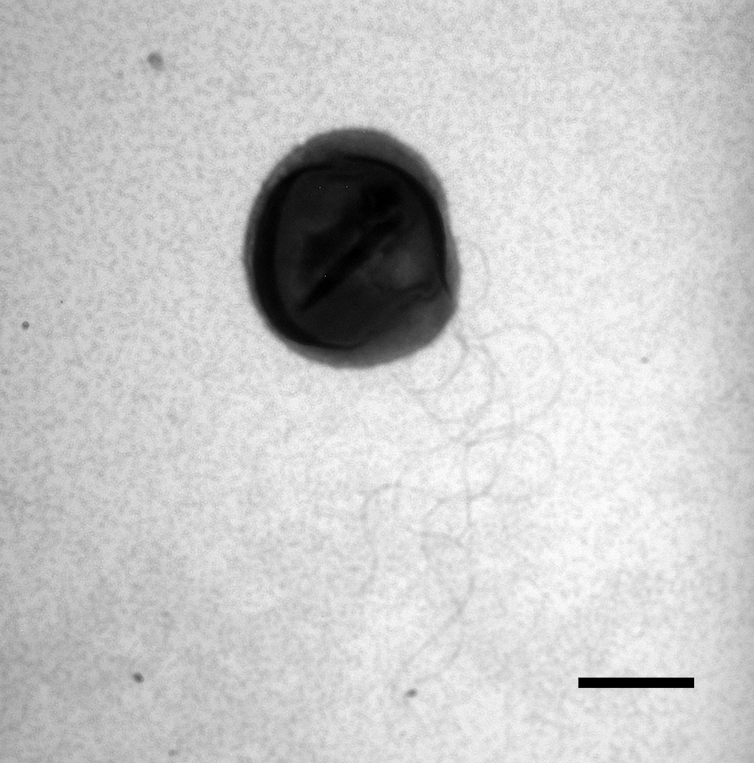

Back in my laboratory in Amherst, my research team isolates new microbes from the hydrothermal vent samples and grows them under conditions that mimic those they experience in nature. We feed them volcanic chemicals like hydrogen, carbon dioxide, sulfur and iron and measure their ability to produce compounds like methane, hydrogen sulfide and the magnetic mineral magnetite.

Lin et al., 2016/The Microbiology Society

Oxygen is typically deadly for these organisms, so we grow them in synthetic hydrothermal fluid and in sealed tubes or in large bioreactors free of oxygen. This way, we can control the temperature and chemical conditions they need for growth.

From these experiments, we look for distinguishing chemical signals that these organisms produce which spacecraft or instruments that land on extraterrestrial surfaces could potentially detect.

We also create computer models that best describe how we think these microbes grow and compete with other organisms in hydrothermal vents. We can apply these models to conditions we think existed on early Earth or on ocean worlds to see how these microbes might fare under those conditions.

We then analyze the proteins from the thermophiles we collect to understand how these organisms function and adapt to changing environmental conditions. All this information guides our understanding of how life can exist in extreme environments on and beyond Earth.

Uses for thermophiles in biotechnology

In addition to providing helpful information to planetary scientists, research on thermophiles provides other benefits as well. Many of the proteins in thermophiles are new to science and useful for biotechnology.

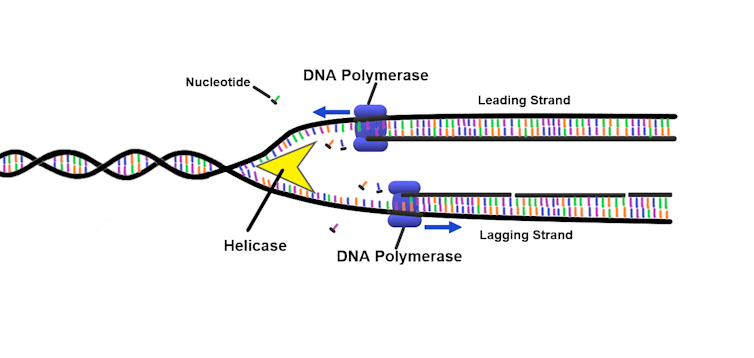

The best example of this is an enzyme called DNA polymerase, which is used to artificially replicate DNA in the lab by the polymerase chain reaction. The DNA polymerase first used for polymerase chain reaction was purified from the thermophilic bacterium Thermus aquaticus in 1976. This enzyme needs to be heat resistant for the replication technique to work. Everything from genome sequencing to clinical diagnoses, crime solving, genealogy tests and genetic engineering uses DNA polymerase.

Christinelmiller/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

My lab and others are exploring how thermophiles can be used to degrade waste and produce commercially useful products. Some of these organisms grow on waste milk from dairy farms and brewery wastewater – materials that cause fish kills and dead zones in ponds and bays. The microbes then produce biohydrogen from the waste – a compound that can be used as an energy source.

Hydrothermal vents are among the most fascinating and unusual environments on Earth. With them, windows to the first life on Earth and beyond may lie at the bottom of our oceans.

![]()

James F. Holden receives funding from NASA.

– ref. Microbes in deep-sea volcanoes can help scientists learn about early life on Earth, or even life beyond our planet – https://theconversation.com/microbes-in-deep-sea-volcanoes-can-help-scientists-learn-about-early-life-on-earth-or-even-life-beyond-our-planet-260977