Source: The Conversation – UK – By Giorgio Di Gessa, Lecturer in Data Science, UCL

Grandparents play a pivotal role in family life. They are often a vital part of the childcare puzzle, stepping in to look after their grandchildren while parents are at work or busy. And there’s a lot of grandparent care taking place.

In England, around half of all grandparents provide care for their grandchildren when the parents are not around. And the percentage of grandparents providing care is even higher when they have grandchildren aged 16 and under, who are more likely to require supervision, care, and support from an adult when the parents are busy at work or unavailable. In this case, 66% of grandparents help out.

I used data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, to analyse the caring roles of over 5,000 grandparents. I used data collected in 2016-17 to assess how often grandparents looked after their grandchildren, the activities they did with them, and why they helped out. I also discovered that there are clear gender and socioeconomic patterns. Further analysis of data from 2018-19 showed that providing care as a grandparent can affect wellbeing.

I found that in England, among grandparents who looked after grandchildren, 45% of grandparents spent at least one day a week looking after their young grandchildren. They did so consistently throughout the year, with 8% doing so almost daily. Approximately one in three grandparents provided care to their grandchildren during school holidays.

Around 25% of grandparents who looked after their grandchildren were still working. Most grandparents reported having overall good physical health.

And most grandparents who cared for their grandchildren also lived relatively close to them – less than half an hour away from their closest grandchild – and had at least one grandchild aged under six years old.

Most of the grandparents in the study who cared for grandchildren – 80% – mentioned that they played or took part in leisure activities with their grandchildren. Around half said that they frequently cooked for them and helped with picking them up and dropping them off from schools and nurseries. And although it was less common, grandparents also helped with homework and taking care of their grandchildren when they were not feeling well.

About three grandparents in four (76%) said that their motivation for helping out was to give their grandchildren’s parents some time out from childcare responsibilities. A similar percentage – 70% – said they wanted to provide some economic support, either by offering financial assistance or by allowing parents to go to work.

Just over half of grandparents (52%) said that being able to provide emotional support was what drove their motivation to provide grandchild care: they wanted to feel engaged with young people and help their grandchildren develop. But 17% say that they felt obliged to help out, and found it difficult to refuse.

The grandmother’s role

But while we tend to talk about “grandparents” as a group, grandmothers and grandfathers often experience and approach caregiving in distinctly different ways.

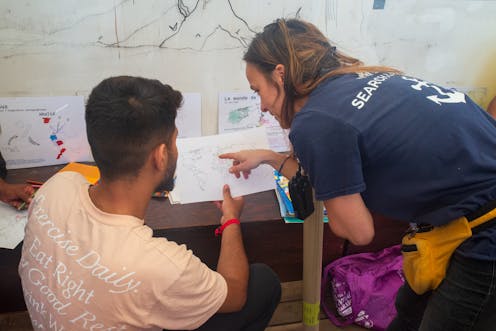

In particular, when examining the specific activities undertaken with their grandchildren, there are clear gender distinctions. I found that grandmothers were more likely than grandfathers to engage in hands-on tasks: preparing meals, helping with homework, caring for grandchildren when they are sick, and doing school pick-ups.

Rawpixel.com/Shutterstock

Grandfathers, while also involved, tended to participate less in these activities. This is the case even among grandparent couples who lived together and jointly cared for their grandchildren.

The role of wealth

The extent and nature of grandparental care is also closely linked to grandparents’ socioeconomic status. For example, grandparents with fewer financial resources tended to offer childcare more regularly than their wealthier counterparts.

Socioeconomic disparities also shape the nature of caregiving tasks. Less affluent grandparents were more likely to engage in hands-on activities, such as cooking meals and taking their grandchildren to and from school. In contrast, grandparents with more education were more likely than those with less education to help with homework frequently.

The reasons for providing care also varied according to grandparents’ socioeconomic status. Grandparents with greater financial resources and higher levels of education were more likely to report providing childcare to help parents manage work and other responsibilities, as well as to offer emotional support to their grandchildren. Conversely, those with fewer financial resources were more likely to feel obliged to help or to struggle to refuse caregiving duties.

Grandparent wellbeing

What grandparents do with their grandchildren and why they have an active role in caring for them can also affect their wellbeing in complex ways. Grandparents who often took part in fun or enriching activities with their grandchildren, such as leisure activities or helping with homework, tended to report higher wellbeing compared to their peers who did not look after grandchildren.

However, grandparents who cared for their grandchildren when they were sick or who had them stay overnight without parents tended to report, over time, lower wellbeing.

Motivations also matter for grandparents’ wellbeing. Grandparents had a higher quality of life if they cared for their grandchildren because they wanted to help them develop as people, or to feel engaged with young people. However, grandparents who felt obliged to help, perhaps due to family pressure or lack of alternatives, experienced lower wellbeing.

In short, these findings remind us that behind the broad label of “grandparenting” lies a diverse world of individuals whose involvement in caring for grandchildren – how often they care, what they do, and why – is closely linked to and varies with gender norms and socioeconomic status.

Also, the meaning behind grandparenting and the type of interactions shared with grandchildren seems to matter for grandparents’ wellbeing. Overall, these insights suggest that these caring responsibilities may contribute to the reinforcement or even deepening of existing gender, socioeconomic and health inequalities among older adults.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

![]()

Giorgio Di Gessa does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Grandparent care: women from poorer backgrounds help out most with childcare – https://theconversation.com/grandparent-care-women-from-poorer-backgrounds-help-out-most-with-childcare-253168