Source: The Conversation – France in French (2) – By Niousha Shahidi, Full professor, data analysis, EDC Paris Business School

Chaque jour, sans même y penser, nous classons les choses : ranger les livres de la bibliothèque selon le genre, classer les e-mails… Mais comment classer des éléments quand on ne dispose pas d’une classification existante ? Les mathématiques peuvent répondre à ce type de questions. Ici, une illustration sur le télétravail.

Dans le cadre du télétravail, nous nous sommes posé la question de savoir si les télétravailleurs peuvent être regroupés en fonction de leur perception de l’autonomie et du contrôle organisationnel.

Ceci nous a permis de justifier mathématiquement que deux grandes classes de télétravailleurs existent, et que leur vision du télétravail diffère. Ceci peut permettre aux managers et aux services de ressources humaines d’adapter le management de chacun en fonction de son profil.

Classer, c’est mesurer la similarité

Nous avons considéré 159 télétravailleurs. Pour classer les individus, il faut d’abord mesurer à quel point ils se ressemblent. Pour cela on identifie des « profils type » à partir de l’évaluation de « construits », qui sont des ensembles de critères qui traitent le même sujet.

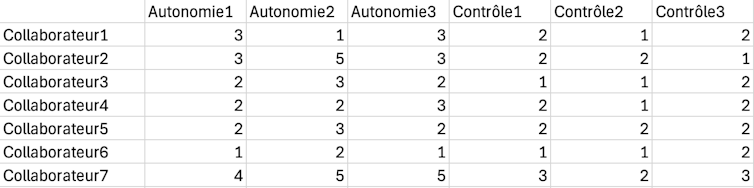

Dans notre étude, les construits principaux sont le contrôle et l’autonomie. On évalue ces deux construits grâce à plusieurs questions posées aux télétravailleurs, par exemple « J’ai l’impression d’être constamment surveillé·e par l’utilisation de la technologie à la maison ». Ceux-ci donnent leur réponse sur une échelle en 5 points (de 1-pas du tout d’accord à 5-tout à fait d’accord).

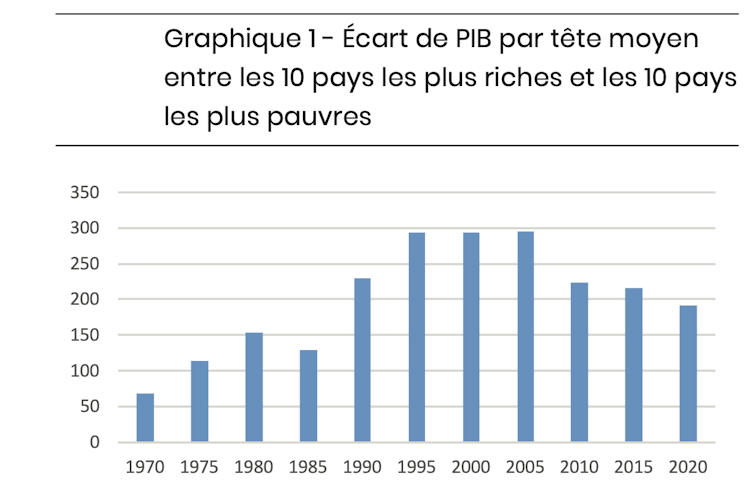

Ensuite, chaque télétravailleur est représenté par une ligne de données : ce sont les réponses du télétravailleur dans l’ordre des critères. Par exemple pour le collaborateur 1, on peut voir les réponses (3, 1, 3, 2…), voir figure.

Données de Diard et al. (2025), Fourni par l’auteur

Pour regrouper les télétravailleurs, il faut d’abord mesurer à quel point ils se ressemblent. Pour cela, on mesure la distance entre les profils (en utilisant des distances euclidiennes). Cette notion de distance est très importante, car c’est elle qui quantifie la similitude entre deux télétravailleurs. Plus deux profils sont proches, plus ils auront vocation à être dans la même classe.

Si on considère autant de classes que de personnes, la séparation est parfaite mais le résultat est sans intérêt. L’enjeu est donc double : avoir un nombre raisonnable de classes distinctes tel que, dans chaque classe, les individus soient suffisamment semblables.

À lire aussi :

Maths au quotidien : pourquoi votre assurance vous propose un contrat avec franchise

Combien de classes choisir ?

Nous avons utilisé la méthode de classification ascendante hiérarchique, qui consiste à regrouper les individus les plus semblables possibles dans une même classe tandis que les classes restent dissemblables.

Plus précisément, au début, chaque télétravailleur est traité comme une classe et on essaie de regrouper deux ou plusieurs classes de manière appropriée pour former une nouvelle classe. On continue ainsi « jusqu’à obtenir la classe tout entière, c’est-à-dire l’échantillon total ». L’arbre aussi obtenu (dendrogramme) peut être coupé à différents niveaux.

Une question importante se pose alors : comment choisir le nombre de classes ? Il existe plusieurs méthodes. Par exemple, la méthode du coude : le point où la courbe (variance intra-classe en fonction du nombre de classes) « fait un coude » correspond au nombre de classes à retenir. Cela signifie que si « on ajoute une classe de plus, on gagne peu en précision ». Dans notre étude, le nombre de classes retenu est deux.

Afin d’améliorer notre classification, nous poursuivons avec une méthode de classification non hiérarchique (k-means) qui répartit à nouveau les télétravailleurs dans deux classes (mais ceux-ci sont légèrement différents) tout en minimisant la distance aux « centres » de classes (scores moyens des critères de chaque classe trouvés précédemment).

Nous découvrons alors deux classes de télétravailleurs mieux répartis : les « satellites-autonomes » et les « dépendants-contrôlés ».

La classification au service du manager

Une fois la classification trouvée, on s’intéresse alors à analyser les scores moyens par rapport aux autres construits du modèle, en l’occurrence l’expérience du télétravailleur. Les « satellites autonomes » ont une vision globalement plus positive de leur travail que les « dépendants contrôlés » et estiment que leurs conditions de travail se sont améliorées depuis la mise en place du télétravail.

Il existe bien sûr des limites à notre étude : il faudra en tester la robustesse, répéter l’analyse avec des sous-échantillons ou d’autres échantillons de télétravailleurs et encore tester plusieurs méthodes de classification. Une nouvelle enquête pourra montrer si le nombre ou la nature des classes que nous avons trouvées évolue. Mais il est important de noter que ce résultat (deux profils de télétravailleurs) est le fruit d’une démarche mathématique et statistique rigoureuse, qui complète les études antérieures qualitatives.

La classification est un outil bien connu en matière de gestion des ressources humaines. Par exemple, elle consiste à « peser » le poste et le positionner dans une grille prédéfinie en comparant son profil aux caractéristiques de quelques postes repères. Chaque convention collective dispose d’une grille de classification. C’est la loi du 23 décembre 1946 et les arrêtés Parodi-Croizat du 11 avril 1946 qui avaient ouvert la voie de la classification des ouvriers en sept échelons.

À l’aide des mathématiques, notre classification montre que le télétravail ne peut pas être géré comme un dispositif unique. Chaque profil correspond à des besoins et à des dynamiques organisationnelles spécifiques. Savoir qu’il existe deux profils majoritaires permet de proposer des actions différenciantes dans l’accompagnement des télétravailleurs.

Les mathématiques sont ici un outil au service du manager et aident à voir des structures invisibles dans un ensemble complexe de données. Il s’agit d’un outil d’aide à la décision.

![]()

Rien à déclarer

Caroline Diard et Niousha Shahidi ne travaillent pas, ne conseillent pas, ne possèdent pas de parts, ne reçoivent pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’ont déclaré aucune autre affiliation que leur poste universitaire.

– ref. Quel type de télétravailleur êtes-vous ? Quand les maths éclairent votre profil – https://theconversation.com/quel-type-de-teletravailleur-etes-vous-quand-les-maths-eclairent-votre-profil-273399