Source: The Conversation – (in Spanish) – By Víctor Resco de Dios, Catedrático de Ingeniería Forestal y Cambio Global, Universitat de Lleida

Los bosques absorben en torno al 30 % de las emisiones de gases con efecto invernadero. Lamentablemente, no sabemos cuánto tiempo durará este “sumidero” de carbono. A raíz de su creciente degradación, los bosques tropicales y boreales podrían liberar cantidades colosales de dióxido de carbono (CO₂) a la atmósfera. Si esto llegara a ocurrir, el cambio climático se aceleraría y amplificaría.

Algunos indicios sugieren que este proceso podría haber empezado ya: las emisiones de CO₂ batieron récords de crecimiento en 2024 debido a los megaincendios tropicales.

Preservar los bosques frente a su degradación y a la deforestación cuesta dinero. Por desgracia, muchos aumentan su valor tras ser transformados en cultivos o minas, o incluso después de un incendio, dado que se pueden cobrar créditos de carbono por la repoblación posterior. La clave para la conservación de los bosques pasa, por tanto, en lograr que el bosque en pie, sano y en buen estado de conservación valga más que un bosque quemado o roturado.

En la cumbre climática de Brasil, la COP30, se presentará un nuevo mecanismo financiero desarrollado con ese fin: la Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF). Antes de explicar en qué consiste, conviene recordar que la TFFF no es la primera iniciativa financiera probiodiversidad.

Leer más:

COP30 de Brasil: una cumbre incierta, pero imprescindible para la acción climática

Gestión por comunidades rurales e indígenas

Los bosques no son ambientes puramente naturales, sino también culturales. Más del 90 %, incluso de los tropicales, han sido gestionados por el hombre durante los últimos 10 000 años. Lo que determina su estado de conservación, por tanto, no es la presencia o ausencia del ser humano, sino qué han hecho los humanos que gestionaban esos ambientes.

Ancestralmente, la preservación de los bosques estaba ligada al aprovechamiento por parte de las comunidades rurales o indígenas, y al posterior desarrollo de cadenas de valor. Esto es, la necesidad de leñas durante muchas generaciones, por ejemplo, fomentaba una gestión de los bosques sostenible en el tiempo.

Esta gestión se vio reforzada a partir del siglo XIX, con la creación de escuelas especializadas como la de los ingenieros de montes, que evaluaron y elevaron el conocimiento tradicional a conocimientos científicos y técnicos. Otro cambio importante lo encontramos en los años 90: se desarrollaron sistemas de certificación forestal que acreditan la sostenibilidad ambiental y social del aprovechamiento y, por ende, aumentan el valor de los productos.

“Canjear deuda por naturaleza”

Durante el siglo XX, sobre todo en la segunda mitad, surge una conciencia ambiental en la sociedad que es capitalizada por oenegés ambientalistas. Estas oenegés han sido muy creativas a la hora de encontrar fuentes de financiación. Un ejemplo lo encontramos en la operativa “canjear deuda por naturaleza”, iniciada por el Fondo Mundial para la Naturaleza (WWF). A través de esta medida, un país del sur global puede ver reducida su deuda exterior (que es adquirida por una ONG o por los gobiernos de otros países) si acomete actuaciones de restauración de la naturaleza.

En 2021, por ejemplo, Belice redujo su deuda exterior en 216 millones de dólares tras comprometerse a destinar 107 millones a la conservación. En la actualidad existen más de 100 proyectos similares. Una parte importante de estos presupuestos se redirigen hacia entidades ambientalistas, que son las encargadas de acometer, o certificar, las actuaciones de restauración en colaboración con los gobiernos.

Los problemas con las entidades ambientalistas

Si bien los objetivos ambientales de estas iniciativas son positivos, se han denunciado los conflictos de interés y prácticas deficientes detrás de esos proyectos.

Este tipo de operativas implican, en la mayoría de casos, la sustitución de comunidades ancestrales por oenegés ambientalistas, tanto en su función como gestores de la tierra como en la recepción de los fondos. Como no podía ser de otra manera, estas medidas han desembocado en una gran tensión entre las oenegés y las comunidades rurales e indígenas.

En el año 2004, el antropólogo Mac Chapin ya advertía sobre cómo las entidades ambientalistas estaban abusando de las comunidades rurales e indígenas. En el tercer congreso de la Unión Internacional de la Naturaleza, Martin Saning’o, portavoz de los masái, declaraba abiertamente que eran enemigos de la conservación de la naturaleza: les estaban echando de sus tierras en pro de una supuesta conservación. Y en 2019 los periodistas Tom Warren y Katie Baker documentaron cómo esas expulsiones estaban siendo agravadas por violaciones, torturas y asesinatos a indígenas por parte de los guardas de reservas naturales, pertenecientes a grupos paramilitares, financiados por WWF.

Además, disciplinas científicas como la ecología o la dasonomía, junto con disciplinas sociales como la historia o la antropología, han documentado que la mejor forma de preservar los bosques está en su gestión por parte de las comunidades rurales o indígenas que de ella dependen.

Las oenegés ecologistas siempre han sido reticentes a admitir esta realidad: si el mejor gestor de la naturaleza está en las comunidades locales, estas entidades dejan de tener sentido. En la actualidad, las evidencias científicas sobre cómo las comunidades locales son las mejores gestoras tan abrumadoras, que han tenido que dar su brazo a torcer y admitirlo abiertamente.

El fondo que se lanzará en la COP30

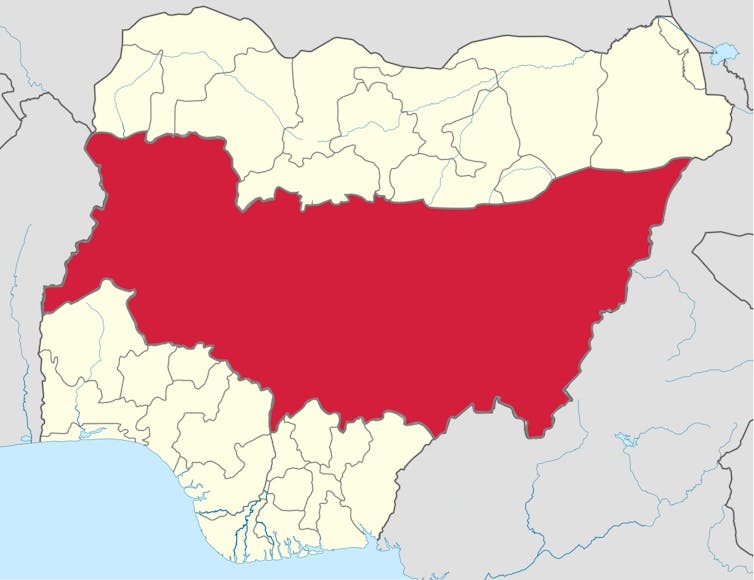

Para conservar la biodiversidad, y asegurar que las comunidades rurales e indígenas siguen gestionando sus ecosistemas ancestrales, se ha diseñado la Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF).

La TFFF sigue un esquema que en esencia ya se esbozó hace más de dos décadas: consiste en pagar por la preservación de los servicios que nos prestan los ecosistemas. Ahora bien, este mecanismo se articula a través de bonos.

En primer lugar, se crea un fondo de inversión alimentado por gobiernos e inversores privados que espera movilizar 125 000 millones de dólares. Este invierte su capital en un portafolio basado en mercados emergentes y economías en desarrollo, de manera que parte de las ganancias van a parar a los países con bosques tropicales seleccionados para recibir pagos.

Se utilizan sistemas de seguimiento forestal para vigilar si ha habido deforestación. Si se cumplen los objetivos, el país receptor recibe 4 dólares por cada hectárea forestal preservada, mientras que la deforestación y la degradación suponen una reducción de los pagos.

La creación de fondos financieros para la conservación de la biodiversidad no es nueva, ni tampoco lo es la venta de bonos, pero sí hay algunos detalles importantes del TFFF que son novedosos. El primero es que, por fin, las comunidades locales serán compensadas por su buen hacer: el 20 % de los ingresos, como mínimo, deben ir a esos gestores ancestrales.

El segundo es que no se financian proyectos particulares, sino políticas públicas. Esto es importante porque, a priori, garantiza que el Gobierno del país velará por su aplicación a escala nacional.

Ahora bien, tenemos que dejar bien claro que se trata de un fondo de inversión que, como cualquier otro, busca ganar dinero preservando la biodiversidad. El fondo especifica que los beneficios irán, en primer lugar, a los inversores y patrocinadores y el remanente, a pagos forestales.

Fondos de inversión parecidos a TFFF están en auge. A principios de año, Golden Sachs desarrolló un fondo que pretende movilizar 500 millones de dólares, nuevamente para preservar la naturaleza.

Estos fondos de inversión siguen la estela marcada por el Convenio de la ONU sobre Biodiversidad, que busca movilizar 200 000 millones de dólares anualmente para conservar la biodiversidad. Estamos hablando de mucho dinero y, en consecuencia, de un negocio colosal.

Necesitamos que los bosques cuidados valgan más que los destrozados. No sabemos si la TFFF, o el fondo de Goldman Sachs, servirá para tal fin. Lo que sí sabemos es que iniciativas similares estaban llenas de buenas intenciones y de grandes fracasos. Esperemos que esta vez sea diferente y que, por una vez, sean las comunidades locales, rurales e indígenas quienes resulten beneficiadas.

![]()

Víctor Resco de Dios recibe fondos del MICINN.

– ref. COP30: por qué debemos ser cautos ante el fondo de 125 000 millones de dólares para conservar bosques tropicales – https://theconversation.com/cop30-por-que-debemos-ser-cautos-ante-el-fondo-de-125-000-millones-de-dolares-para-conservar-bosques-tropicales-269142