Source: The Conversation – France in French (3) – By Hugo Spring-Ragain, Doctorant en économie / économie mathématique, Centre d’études diplomatiques et stratégiques (CEDS)

En 2023, le taux de pauvreté a dépassé 15 % en France. Cela n’est pas tant le résultat d’une conjoncture économique défavorable que la conséquence de changements structurels emportant des mutations de long terme. Le sujet mérite d’autant plus d’être observé car, au-delà de la situation des personnes concernées, il remet en cause la stabilité des institutions politiques.

En 2023, la France a enregistré un taux de pauvreté monétaire record, atteignant 15,4 %, soit un niveau inédit depuis 1996. La question de la soutenabilité du modèle socio-économique des démocraties occidentales revient au premier plan. Cette progression de la pauvreté ne relève pas uniquement d’un choc conjoncturel, mais témoigne d’une mutation plus profonde du rapport entre croissance, redistribution et cohésion sociale. Le retour de la pauvreté de masse, y compris dans des catégories jusqu’ici intégrées au salariat protégé, signale une possible rupture de régime dans la promesse implicite d’ascension sociale et de protection des plus vulnérables.

La conjoncture n’explique pas tout

Le taux de pauvreté monétaire a atteint 15,4 % en France en 2023, soit le niveau le plus élevé depuis 1996. Cette progression significative (+0,9 point en un an, soit environ 650 000 personnes supplémentaires) interroge profondément les fondements socio-économiques des pays développés. Loin d’un simple effet de conjoncture (inflation, crise énergétique ou guerre en Ukraine), cette inflexion marque une tendance structurelle : la multiplication des zones de précarité latente – vulnérabilité économique persistante, souvent masquée par l’emploi ou des ressources instables, mais exposée au moindre choc – dans les segments inférieurs et médians de la distribution des revenus.

À lire aussi :

Polanyi, un auteur pour mieux comprendre ce qui nous arrive

Les déterminants structurels de l’augmentation de la pauvreté sont multiples : montée des emplois atypiques (et ubérisation), stagnation des salaires réels pour les déciles médians, dualisation du marché du travail, déformation du partage de la valeur ajoutée au détriment du facteur travail et réduction de l’investissement public dans certains services collectifs essentiels. À cela s’ajoutent des dynamiques territoriales inégalitaires où les zones rurales, périurbaines et certains centres urbains dégradés cumulent désindustrialisation, isolement social et sous-dotation en infrastructures publiques comme privées.

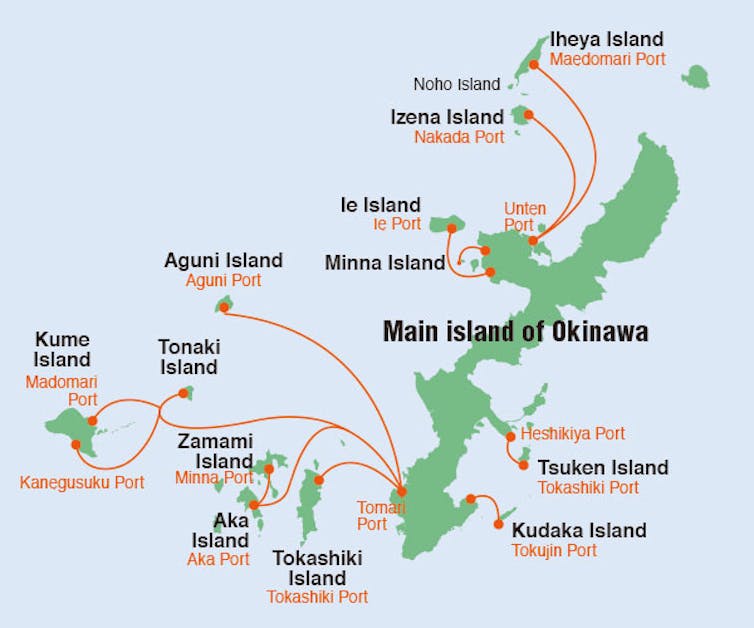

Figure – Évolution comparée des niveaux de vie (D1, D5, D9) en France, 1996–2023, avant et après redistribution. – Source : Insee

Lecture : les courbes montrent l’évolution des revenus des 1er, 5e et 9e déciles, en euros constants (base 100 en 2008). Avant redistribution, les écarts sont beaucoup plus prononcés, notamment entre D1 et D9. L’effet redistributif réduit significativement ces écarts, mais ne suffit pas à inverser les dynamiques inégalitaires de long terme. La stagnation du bas de l’échelle (D1) reste visible même après transferts sociaux, alors que le haut (D9) progresse nettement.

Des amortisseurs sociaux de moins en moins opérants

Si les transferts sociaux jouent encore un rôle crucial dans la réduction de la pauvreté (le taux brut atteindrait 21,7 % sans redistribution), leur efficacité relative diminue. Non seulement ils ne parviennent plus à enrayer la montée tendancielle de la pauvreté, mais ils peinent aussi à répondre à la complexité des situations contemporaines : travailleurs pauvres, jeunes diplômés sous-employés, femmes seules avec enfants ou encore retraités vivant sous le seuil de pauvreté (1288 euros).

Ce glissement progressif traduit une rupture dans le compromis fordiste sur lequel reposait la cohésion des économies occidentales : emploi stable, protection sociale contributive et croissance redistributive. Il met également en tension la soutenabilité politique du modèle social à mesure que les classes moyennes perçoivent ces transferts comme moins universels et plus segmentés.

Ce phénomène n’est pas propre à la France : les économies occidentales dans leur ensemble connaissent une montée d’une pauvreté dite « intégrée », c’est-à-dire présente au sein même du salariat. Dans les pays de l’OCDE, plus de 7 % des travailleurs sont aujourd’hui pauvres, signe que l’emploi ne protège plus systématiquement du besoin. Cette évolution remet en cause le postulat selon lequel le marché du travail constitue un vecteur naturel d’intégration économique et sociale. En parallèle, les écarts de niveau de vie entre les déciles extrêmes s’élargissent, accentuant la fragmentation du tissu social.

Les classes moyennes déstabilisées

Au-delà de la pauvreté en tant que phénomène statistique, c’est l’évolution relative des positions sociales qui alimente un sentiment profond de déclassement. Les classes moyennes, longtemps considérées comme les piliers de la stabilité démocratique et de la croissance domestique, sont désormais prises en étau. D’un côté, la paupérisation des actifs précaires et la fragilité de l’emploi fragmenté ; de l’autre, l’accumulation exponentielle de capital chez les 10 % les plus riches et plus encore chez les 1 % supérieurs. Il est ici essentiel de distinguer les flux de revenus (salaires, prestations) des stocks patrimoniaux, dont la concentration alimente des écarts croissants sur le long terme, indépendamment des efforts individuels.

Cette polarisation résulte de dynamiques économiques profondes : concentration du capital immobilier et financier, désindexation salariale, évolution défavorable du capital humain dans les secteurs intermédiaires et fiscalité régressive dans certains segments. Les gains de productivité ne se traduisent plus par des hausses de salaire ; la fonction d’utilité des agents tend à se contracter dans les déciles intermédiaires et les effets de seuils fiscaux, sociaux ou réglementaires amplifient les discontinuités dans les trajectoires de vie.

Perte de foi dans la promesse méritocratique

On assiste ainsi à une recomposition en sablier de la structure sociale : précarité durable en bas, enrichissement du haut, et effritement du centre. Dans ce contexte, la perception d’une mobilité sociale bloquée, ou, pire, inversée renforce le désengagement civique, la frustration relative et la radicalisation des préférences politiques. Ce que révèlent les indicateurs de pauvreté ne relève donc pas uniquement d’un appauvrissement objectif mais bien d’une perte d’espérance en la promesse méritocratique au cœur de la légitimation démocratique.

La situation est d’autant plus préoccupante que les variables d’ajustement traditionnelles comme l’éducation, le travail qualifié ou l’accession à la propriété ne jouent plus leur rôle d’ascenseur. L’immobilité relative des positions intergénérationnelles, combinée à l’explosion du coût de l’entrée dans la classe moyenne (logement, études, santé), tend à enfermer les individus dans leur position initiale. Autrement dit, la pauvreté s’ancre dans des dynamiques d’exclusion durables plus difficilement réversibles que par le passé.

Une crise de soutenabilité du contrat social démocratique

L’universalité du filet de sécurité et la promesse de mobilité sociale ascendante constituaient les deux piliers implicites du contrat social des économies libérales avancées, or ces deux fondements sont aujourd’hui ébranlés. L’universalité tend à se fragmenter sous l’effet de ciblages budgétaires croissants et d’un tri social plus restrictif dans l’accès aux droits sociaux. La mobilité, quant à elle, est de moins en moins portée par les fonctions traditionnelles de l’école, de l’emploi et du logement.

La question centrale devient donc : nos démocraties disposent-elles encore des moyens économiques et politiques pour corriger les déséquilibres que leur propre trajectoire historique a produits ? Plusieurs options sont sur la table : réforme de la fiscalité sur les hauts patrimoines, réinvestissement dans les infrastructures sociales, redéfinition des politiques d’emploi, expérimentation de mécanismes de revenu minimum garanti, remise à zéro du modèle social. Mais leur mise en œuvre se heurte à une contrainte majeure : le consentement fiscal des classes moyennes, précisément celles dont la position socio-économique est la plus fragilisée.

Le taux de pauvreté à 15,4 % est plus qu’un indicateur social. Il traduit une perte d’efficacité du modèle redistributif, une fragmentation des trajectoires individuelles et une mise en tension du pacte démocratique. Le défi est donc double : restaurer une forme d’égalité réelle tout en reconstruisant les conditions d’un consentement collectif à la solidarité.

![]()

Hugo Spring-Ragain ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. La pauvreté de masse : symptôme d’une crise de la cohésion sociale – https://theconversation.com/la-pauvrete-de-masse-symptome-dune-crise-de-la-cohesion-sociale-261486