Source: The Conversation – (in Spanish) – By Laura Damas Mollá, Investigadora en Geología, Universidad del País Vasco / Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea

Este artículo forma parte de la sección The Conversation Júnior, en la que especialistas de las principales universidades y centros de investigación contestan a las dudas de jóvenes curiosos de entre 12 y 16 años. Podéis enviar vuestras preguntas a tcesjunior@theconversation.com

Pregunta formulada por el curso de 2º de la ESO del Instituto de Educación Secundaria Miguel de Unamuno, en Gasteiz (Álava)

Nuestro planeta es mucho, muchísimo más antiguo que cualquier civilización humana. Sus 4 500 millones de años de historia han dejado numerosas huellas en las rocas, y la geología es la ciencia que se encarga de descifrarlas para que podamos leer los diferentes capítulos del “libro de la Tierra”, con tramas que se entrelazan.

Hablan los sedimentos

Antes que nada, recordemos que las rocas tienen varios orígenes: a través de magma o lava se forman las ígneas y por transformación de otras rocas, las metamórficas. Pero aquí las que más nos interesan, de momento, son las del tercer grupo: las sedimentarias.

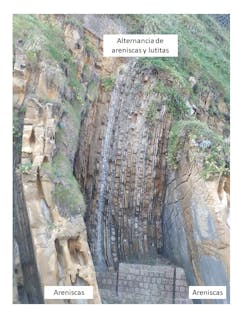

Las rocas sedimentarias nacen al acumularse partículas, más o menos finas, generadas por la descomposición y erosión de rocas que afloran en relieves elevados como montañas. Estas partículas son transportadas por distintas vías (ríos, viento, glaciares…) hacia las zonas de acumulación. Así, los sedimentos se van depositando, capa a capa, en niveles más o menos horizontales: los estratos.

Laura Damas Mollá

Según la llamada ley de horizontalidad de los estratos, establecida por el científico danés Nicolás Steno en el siglo XVII, el estrato inferior es el más antiguo. El problema es que no nos los encontramos siempre así.

Laura Damas Mollá

Al estudiar las rocas sedimentarias, el primer dato que debemos deducir es dónde se depositaron sus materiales, o sea, saber si se formaron en mares, ríos, lagos…. Los restos fósiles de seres vivos nos pueden proporcionar la solución del problema. Así, una roca caliza con fósiles de organismos marinos, como moluscos o corales, surgió en un ambiente tropical de aguas poco profundas, porque la fauna es similar a la actual. Si esos fósiles se encuentran enteros podemos incluso llegar a reconstruir los arrecifes.

Por otro lado, si nos encontramos los fósiles rotos y mezclados, supondremos que algún tipo de corriente los ha removido y desplazado de su hábitat. En otras ocasiones, como ocurre con las areniscas, presentan finas líneas o lineaciones que marcan la dirección e incluso el sentido de las corrientes que transportaban los sedimentos, igual que pasa actualmente en la playa.

Estas piezas del puzle de la historia terrestre se interpretan según el principio del “actualismo”. Acuñado por el geólogo británico Charles Lyell en 1830, indica que “el presente es la clave para entender el pasado”.

Laura Damas Mollá

Detalles que delatan la edad

Con estas pistas es posible interpretar el ambiente donde se depositaron las rocas sedimentarias, pero aún no sabemos su edad. Para averiguarla también existen varias técnicas.

En primer lugar, los minerales que forman esas rocas contienen isótopos radioactivos, componentes químicos cuyo análisis nos permite saber cuánto tiempo llevan en la Tierra. Este método se basa en la desintegración de un isótopo “padre” que se va transformando de forma progresiva a lo largo del tiempo en su “hijo”. Al conocer la proporción existente entre ellos en la muestra se puede obtener su edad.

En el caso de la célebre técnica del carbono-14 se necesitan muestras con un origen orgánico, por lo que no se puede aplicar en muchas rocas y minerales. Además, la “vida” de ese isótopo es de poco más de 60 000 años. Para rocas, minerales y fósiles utilizamos otras relaciones de isótopos radioactivos, como el uranio/torio o el uranio/plomo, que permiten dataciones de entre 500 000 años y varios miles de millones de años, más adecuadas para conocer la larga historia de la Tierra.

Y una curiosidad: ¿sabías que existe también una técnica para saber la edad de la última vez que ha visto la luz del sol un grano de cuarzo? Se llama luminiscencia ópticamente estimulada y se utiliza para estimar la antigüedad de muestras de entre 1 000 y 500 000 años.

Pero estas herramientas no sirven para todo tipo de rocas, así que también usamos otros métodos de datación. El más conocido consiste en examinar la variación del contenido fósil a lo largo del tiempo; es decir, la evolución. La vida de la Tierra se transforma a lo largo del tiempo, y encontrar determinadas asociaciones de fósiles nos permite establecer un rango de edad para los estratos. Aunque los más famosos son los grandes fósiles, como los dinosaurios, normalmente utilizamos microfósiles que se estudian con lupas.

Rocas sometidas a “torturas” geológicas

Pero la historia de las rocas está incompleta si solo averiguamos el ambiente donde se forjaron y su edad. Diferentes procesos geológicos hacen que rocas nacidas en fondos marinos, por ejemplo, formen parte de las montañas actuales. Porque desde que se produce el depósito de los materiales hasta la actualidad, las rocas sedimentarias sufren un proceso que se llama diagénesis: se calientan, se aplastan por enterramiento y experimentan diversos cambios en sus componentes (algunos se disuelven, otros se transforman, otros se fracturan…).

La mayor parte del tiempo, una roca sedimentaria está sometida a esas “torturas”, que podemos entender y ordenar cronológicamente. Para ello utilizados unos microscopios especiales, llamados petrográficos, y láminas de rocas de 0,3 mm de espesor.

Y por si esto fuera poco, los estratos no siempre se encuentran en posición horizontal, como las capas de una tarta. Igual que cuando empujamos un mantel con la mano, las fuerzas de las placas tectónicas pliegan los estratos rocosos. Los geólogos tenemos que “leer” también los capítulos protagonizados por las rocas ígneas, que nos cuentan la historia de las erupciones volcánicas del pasado, y las metamórficas, que nos hablan de transformaciones de unas rocas en otras.

Así, poco a poco, reconstruimos la biografía del planeta, desde las variaciones ambientales a la evolución de la vida. Comprender esa historia nos permite entender los cambios que están ocurriendo hoy en día y reflexionar sobre nuestro breve capítulo como homínidos, ya que la Tierra seguirá transformándose más allá de nuestra presencia en ella.

Si miras a tu alrededor y te pones las gafas de geólogo o geóloga, descubrirás qué historias conservan las rocas para saber hacia dónde vamos.

La Cátedra de Cultura Científica de la Universidad del País Vasco colabora en la sección The Conversation Júnior.

![]()

Laura Damas Mollá no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

– ref. ¿Cómo podemos conocer la historia de la Tierra? – https://theconversation.com/como-podemos-conocer-la-historia-de-la-tierra-266404