Source: The Conversation – (in Spanish) – By Juan J. Muñoz, Profesor de Ingeniería Costera, Universidad de Cádiz

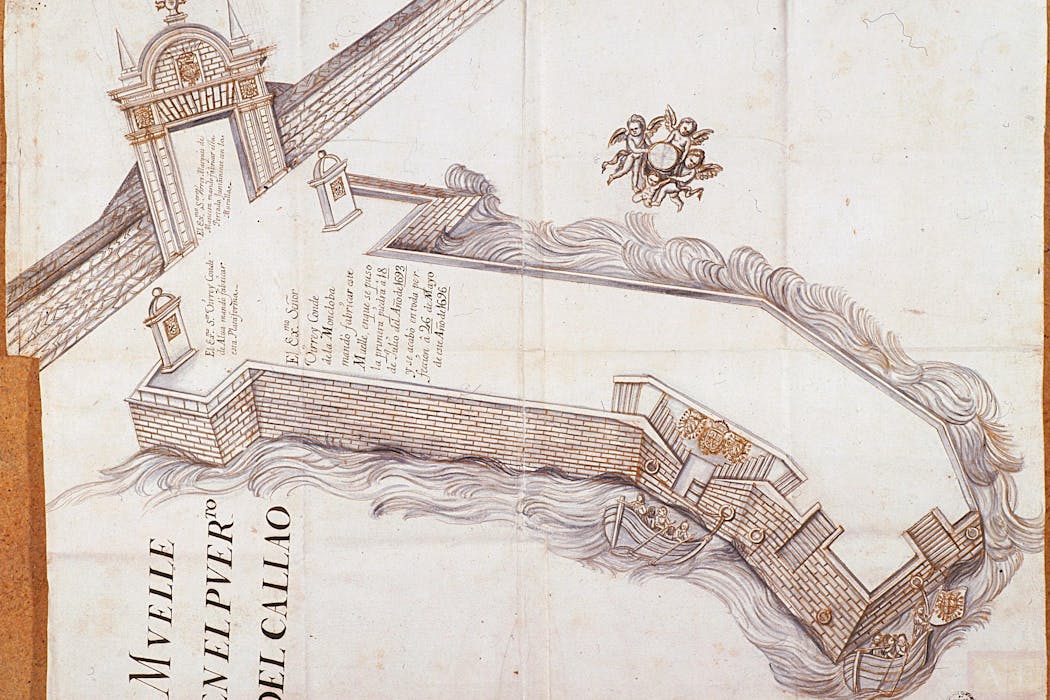

A comienzos del siglo XVIII, el puerto del Callao –la puerta marítima del virreinato del Perú– vivía sitiado por el mar. Las tormentas, los terremotos y los tsunamis golpeaban sin descanso las murallas que protegían el principal punto de salida del oro y la plata rumbo a España.

Lo que pocos saben es que allí, hace 300 años, se ensayó por primera vez en América una regeneración de playas, una idea que hoy sigue siendo una herramienta fundamental de la ingeniería costera moderna.

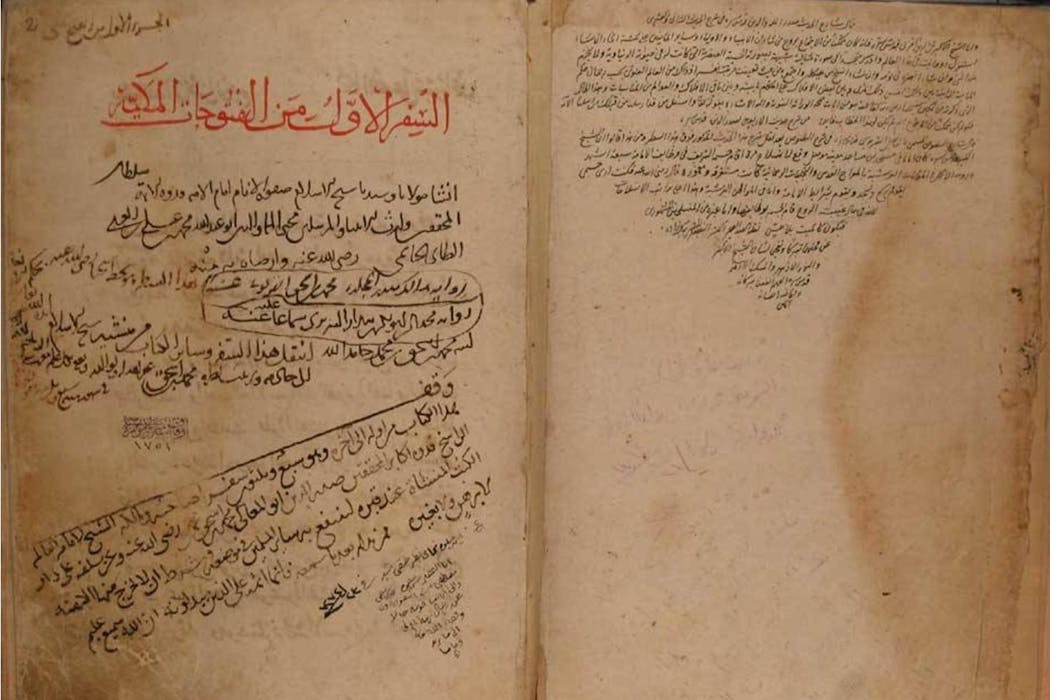

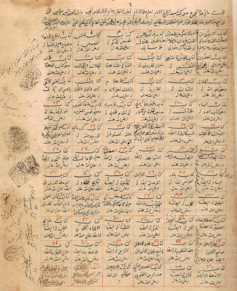

Biblioteca Nacional de España

Un puerto vital y vulnerable

El Callao no era un puerto cualquiera: de él dependía buena parte del comercio entre Sudamérica y Europa. Los metales preciosos que llegaban desde Potosí y el Alto Perú se almacenaban en sus depósitos antes de embarcar hacia Panamá y, luego, a La Habana, donde se organizaba la travesía final hacia la península ibérica. La seguridad de estas operaciones era una prioridad estratégica para la Corona española.

En este contexto, hacia finales del siglo XVII, la construcción de un muelle para facilitar el embarque alteró el equilibrio natural de las corrientes y del transporte de arena. Las arenas se acumulaban en un lado del muelle, pero el otro comenzó a erosionarse con rapidez. En pocas décadas, el mar había socavado los cimientos de las murallas y provocado el derrumbe de parte de la fortificación.

Ingenieros del imperio frente al mar

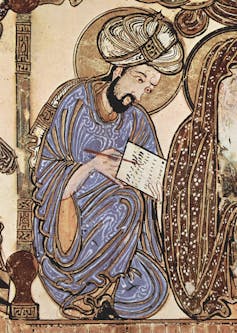

La respuesta llegó de la mano de los ingenieros militares del virreinato. Como recuerda el ingeniero e historiador Ignacio González Tascón (1947–2006) en su libro Ingeniería española en ultramar (CEHOPU, 1992), aquellos técnicos eran auténticos pioneros: dominaban la geometría, la hidráulica y la construcción de obras marítimas con un nivel de precisión asombroso para su época. González Tascón dedicó su vida a rescatar el legado de la ingeniería española en ultramar y su trabajo sigue siendo una referencia esencial para comprender aquel conocimiento técnico adelantado a su tiempo.

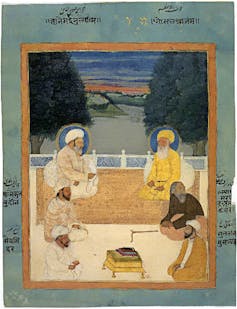

Archivo General de Indias.

El primer intento de reconstrucción lo dirigió el capitán Nicolás Rodríguez, que, para aislar la zona de trabajo del mar, propuso una obra de tablestacado –estructura de contención de suelos y defensa de costas formada por la unión continua de elementos prefabricados (tablestacas), hincados verticalmente en el terreno–. Pero el fondo arenoso filtraba el agua con rapidez y la solución resultaba costosa y poco fiable.

Entonces, intervino el cosmógrafo real Pedro de Peralta Barnuevo (1663-1743), una de las mentes científicas más brillantes del Perú colonial y rector de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos en Lima, la más antigua de América.

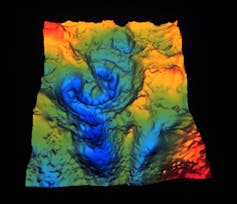

De Peralta planteó una idea radical: construir diques perpendiculares a la costa –lo que hoy llamamos espigones o “groins”– que interrumpieran la corriente litoral y provocaran la acumulación de arena. Así, se formaría una playa artificial frente a la muralla, creando una base seca y estable sobre la que trabajar. Fue, en esencia, la primera regeneración de playas documentada del continente americano.

La playa que salvó una muralla

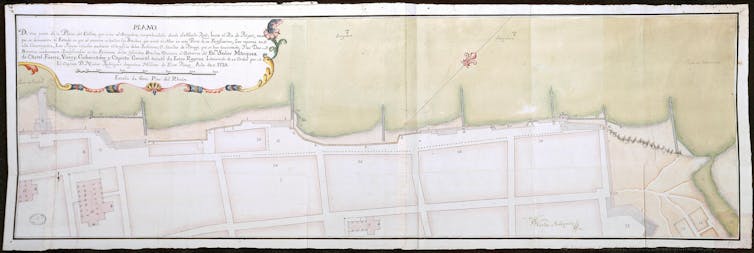

El proyecto comenzó en 1724. Los ingenieros levantaron una serie de espigones de madera y piedra, dispuestos a intervalos regulares, con una proporción entre longitud y separación similar a la de los campos de espigones modernos. Entre ellos, colocaron hileras de gaviones –caja de forma prismática rectangular, rellena de piedra o tierra– para retener el sedimento. En pocos años, las arenas se acumularon en el lado occidental, formando una franja de playa que amortiguaba el impacto de las olas.

Los planos conservados en el Archivo General de Indias muestran con detalle la obra terminada: ocho estructuras alineadas frente a la muralla marítima y una nueva línea de costa protegida. El sistema funcionó. Por primera vez, los ingenieros del virreinato habían conseguido modificar la dinámica litoral para defender una infraestructura clave.

Décadas más tarde, un estudio científico publicado en la revista Water ) corroboraría que aquellas defensas pueden considerarse el primer campo de espigones de Sudamérica, además de una demostración temprana del conocimiento empírico sobre el transporte litoral de sedimentos.

Ciencia, desastres y una lección olvidada

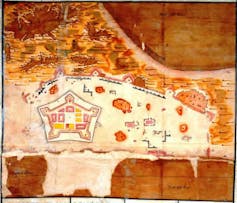

La historia tuvo, sin embargo, un desenlace trágico. El 28 de octubre de 1746, un gran terremoto y un tsunami arrasaron el Callao. La ola, estimada en más de 15 metros, destruyó completamente la ciudad y se llevó consigo las defensas costeras. Murieron casi todos sus habitantes. El virreinato comprendió entonces que el mar podía vencer a la mejor ingeniería de su tiempo.

Anónimo / Biblioteca de Cataluña.

En las décadas siguientes, los virreyes decidieron reconstruir el puerto tierra adentro, junto a la fortaleza del Real Felipe, sobre un terreno más elevado y protegido. Sin saberlo, estaban aplicando un principio que hoy consideramos una de las estrategias más sostenibles frente al cambio climático: el retroceso planificado.

Tres siglos de vigencia

El caso del Callao demuestra que los ingenieros del siglo XVIII ya comprendían la relación entre erosión, corrientes y transporte de arena, y que buscaban soluciones basadas en la observación y el ensayo. No trabajaban con modelos numéricos ni imágenes satelitales, pero su comprensión del litoral era notablemente precisa.

Hoy, cuando la subida del nivel del mar y la pérdida de playas amenazan ciudades costeras de todo el mundo, aquella experiencia del virreinato del Perú cobra un nuevo sentido. En cierto modo, los ingenieros coloniales fueron precursores de las actuales políticas de adaptación costera: supieron leer la dinámica del mar y actuar con ingenio, aun en un contexto tecnológico rudimentario.

Como señaló González Tascón, la ingeniería en ultramar fue también “una ciencia de frontera”. Sus autores trabajaban en el límite entre el conocimiento técnico y la supervivencia cotidiana frente a la naturaleza. Y, como demuestra este episodio, su legado sigue inspirando soluciones tres siglos después.

Un puente entre historia y futuro

El valor del caso del Callao –y del virreinato del Perú, en general– va más allá de la historia de una obra singular. Es el testimonio de un modo de pensar la costa, de entender que la ingeniería no puede imponerse al mar. Se trata, más bien, de dialogar con él.

Recordar esas primeras regeneraciones de playa no solo rescata un fragmento de patrimonio técnico e histórico; también nos recuerda que, ante la amenaza global de la erosión costera, las mejores ideas del futuro pueden tener raíces muy antiguas.

![]()

Las personas firmantes no son asalariadas, ni consultoras, ni poseen acciones, ni reciben financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y han declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado anteriormente.

– ref. Cuando el virreinato del Perú inventó la ingeniería costera americana – https://theconversation.com/cuando-el-virreinato-del-peru-invento-la-ingenieria-costera-americana-268583