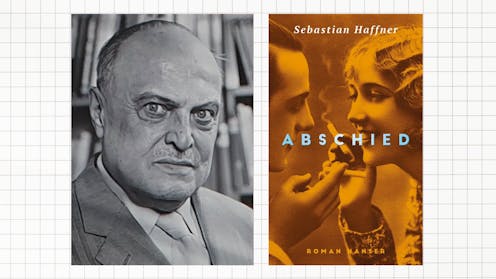

Source: The Conversation – UK – By Peter Bloom, Professor of Management, University of Essex

Across much of Europe, the engines of economic growth are sputtering. In its latest global outlook, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) sharply downgraded its forecasts for the UK and Europe, warning that the continent faces persistent economic bumps in the road.

Globally, the World Bank recently said this decade is likely to be the weakest for growth since the 1960s. “Outside of Asia, the developing world is becoming a development-free zone,” the bank’s chief economist warned.

The UK economy went into reverse in April 2025, shrinking by 0.3%. The announcement came a day after the UK chancellor, Rachel Reeves, delivered her spending review to the House of Commons with a speech that mentioned the word “growth” nine times – including promising “a Growth Mission Fund to expedite local projects that are important for growth”:

I said that we wanted growth in all parts of Britain – and, Mr Speaker, I meant it.

Across Europe, a long-term economic forecast to 2040 predicted annual growth of just 0.9% over the next 15 years – down from 1.3% in the decade before COVID. And this forecast was in December 2024, before Donald Trump’s aggressive tariff policies had reignited trade tensions between the US and Europe (and pretty much everywhere else in the world).

Even before Trump’s tariffs, the reality was clear to many economic experts. “Europe’s tragedy”, as one columnist put it, is that it is “deeply uncompetitive, with poor productivity, lagging in technology and AI, and suffering from regulatory overload”. In his 2024 report on European (un)competitiveness, Mario Draghi – former president of the European Central Bank (and then, briefly, Italy’s prime minister) – warned that without radical policy overhauls and investment, Europe faces “a slow agony” of relative decline.

To date, the typical response of electorates has been to blame the policymakers and replace their governments at the first opportunity. Meanwhile, politicians of all shades whisper sweet nothings about how they alone know how to find new sources of growth – most commonly, from the magic AI tree. Because growth, with its widely accepted power to deliver greater productivity and prosperity, remains a key pillar in European politics, upheld by all parties as the benchmark of credibility, progress and control.

But what if the sobering truth is that growth is no longer reliably attainable – across Europe at least? Not just this year or this decade but, in any meaningful sense, ever?

The Insights section is committed to high-quality longform journalism. Our editors work with academics from many different backgrounds who are tackling a wide range of societal and scientific challenges.

For a continent like Europe – with limited land and no more empires to exploit, ageing populations, major climate concerns and electorates demanding ever-stricter barriers to immigration – the conditions that once underpinned steady economic expansion may no longer exist. And in the UK more than most European countries, these issues are compounded by high levels of long-term sickness, early retirement and economic inactivity among working-age adults.

As the European Parliament suggested back in 2023, the time may be coming when we are forced to look “beyond growth” – not because we want to, but because there is no other realistic option for many European nations.

But will the public ever accept this new reality? As an expert in how public policy can be used to transform economies and societies, my question is not whether a world without growth is morally superior or more sustainable (though it may be both). Rather, I’m exploring if it’s ever possible for political parties to be honest about a “post-growth world” and still get elected – or will voters simply turn to the next leader who promises they know the secret of perpetual growth, however sketchy the evidence?

Pixelvario/Shutterstock

What drives growth?

To understand why Europe in particular is having such a hard time generating economic growth, first we need to understand what drives it – and why some countries are better placed than others in terms of productivity (the ability to keep their economy growing).

Economists have a relatively straightforward answer. At its core, growth comes from two factors: labour and capital (machinery, technology and the like). So, for your economy to grow, you either need more people working (to make more stuff), or the same amount of workers need to become more productive – by using better machines, tools and technologies.

The first issue is labour. Europe’s working-age population is, for the most part, shrinking fast. Thanks to decades of declining birth rates (linked with rising life expectancy and higher incomes), along with increasing resistance to immigration, many European countries face declines in their working population. “”). Rural and urban regions of Europe alike are experiencing structural ageing and depopulation trends that make traditional economic growth ever harder to achieve.

Historically, population growth has gone hand-in-hand with economic expansion. In the postwar years, countries such as France, Germany and the UK experienced booming birth rates and major waves of immigration. That expanding labour force fuelled industrial production, consumer demand and economic growth.

Ageing populations not only reduce the size of the active labour force, they place more pressure on health and other public services, as well as pension systems. Some regions have attempted to compensate with more liberal migration policies, but public resistance to immigration is strong – reflected in increased support for rightwing and populist parties that advocate for stricter immigration controls.

While the UK’s median age is now over 40, it has a birthrate advantage over countries such as Germany and Italy, thanks largely to the influx of immigrants from its former colonies in the second half of the 20th century. But whether this translates into meaningful and sustainable growth depends heavily on labour market participation and the quality of investment – particularly in productivity-enhancing sectors like green technology, infrastructure and education – all of which remain uncertain.

If Europe can’t rely on more workers, then to achieve growth, its existing workers must become more productive. And here, we arrive at the second half of the equation: capital. The usual hope is that investments in new technologies – particularly AI as it drives a new wave of automation – will make up the difference.

In January, the UK’s prime minister, Keir Starmer, called AI “the defining opportunity of our generation” while announcing he had agreed to take forward all 50 recommendations set out in an independent AI action plan. Not to be outdone, the European Commission unveiled its AI continent action plan in April.

But Europe is also falling behind in the global race to harness the economic potential of AI, trailing both the US and China. The US, in particular, has surged ahead in developing and deploying AI tools across sectors such as healthcare, finance, manufacturing and logistics, while China has leveraged its huge state-supported, open-source industrial policy to scale its digital economy.

Despite the EU’s concerted efforts to enhance its digital competitiveness, a 2024 McKinsey report found that US corporations invested around €700 billion more in capital expenditure and R&D, in 2022 alone than their European counterparts, underscoring the continent’s investment gap. And where AI is adopted, it tends to concentrate gains in a few superstar companies or cities.

In fact, this disconnect between firm-level innovation and national growth is one of the defining features of the current era. Tech clusters in cities like Paris, Amsterdam and Stockholm may generate unicorn startups and record-breaking valuations, but they’re not enough to move the needle on GDP growth across Europe as a whole. The gains are often too narrow, the spillovers too weak and the social returns too uneven.

Yet admitting this publicly remains politically taboo. Can any European leader look their citizens in the eye and say: “We’re living in a post-growth world”? Or rather, can they say it and still hope to win another election?

The human need for growth

To be human is to grow – physically, psychologically, financially; in the richness of our relationships, imagination and ambitions. Few people would be happy with the prospect of being consigned to do the same job for the same money for the rest of their lives – as the collapse of the Soviet Union demonstrated. Which makes the prospect of selling a post-growth future to people sound almost inhuman.

Even those who care little about money and success usually strive to create better futures for themselves, their families and communities. When that sense of opportunity and forward motion is absent or frustrated, it can lead to malaise, disillusionment and in extreme cases, despair.

The health consequences of long-term economic decline are increasingly described as “diseases of despair” – rising rates of suicide, substance abuse and alcohol-related deaths concentrated in struggling communities. Recessions reliably fuel psychological distress and demand for mental healthcare, as seen during the eurozone crisis when Greece experienced surging levels of depression and declining self-rated health, particularly among the unemployed – with job loss, insecurity and austerity all contributing to emotional suffering and social fragmentation.

These trends don’t just affect the vulnerable; even those who appear relatively secure often experience “anticipatory anxiety” – a persistent fear of losing their foothold and slipping into instability. In communities, both rural and urban, that are wrestling with long-term decline, “left-behind” residents often describe a deep sense of abandonment by governments and society more generally – prompting calls for recovery strategies that address despair not merely as a mental health issue, but as a wider economic and social condition.

The belief in opportunity and upward mobility – long embodied in US culture by “the American dream” – has historically served as a powerful psychological buffer, fostering resilience and purpose even amid systemic barriers. However, as inequality widens and while career opportunities for many appear to narrow, research shows the gap between aspiration and reality can lead to disillusionment, chronic stress and increased psychological distress – particularly among marginalised groups. These feelings are only intensified in the age of social media, where constant exposure to curated success stories fuels social comparison and deepens the sense of falling behind.

For younger people in the UK and many parts of Europe, the fact that so much capital is tied up in housing means opportunity depends less on effort or merit and more on whether their parents own property – meaning they could pass some of its value down to their children.

Stagnation also manifests in more subtle but no less damaging ways. Take infrastructure. In many countries, the true cost of flatlining growth has been absorbed not through dramatic collapse but quiet decay.

Across the UK, more than 1.5 million children are learning in crumbling school buildings, with some forced into makeshift classrooms for years after being evacuated due to safety concerns. In healthcare, the total NHS repair backlog has reached £13.8 billion, leading to hundreds of critical incidents – from leaking roofs to collapsing ceilings – and the loss of vital clinical time.

Meanwhile, neglected government buildings across the country are affecting everything from prison safety to courtroom access, with thousands of cases disrupted due to structural failures and fire safety risks. These are not headlines but lived realities – the hidden toll of underinvestment, quietly hollowing out the state behind a veneer of functionality.

Without economic growth, governments face a stark dilemma: to raise revenues through higher taxes, or make further rounds of spending cuts. Either path has deep social and political implications – especially for inequality. The question becomes not just how to balance the books but how to do so fairly – and whether the public might support a post-growth agenda framed explicitly around reducing inequality, even if it also means paying more taxes.

In fact, public attitudes suggest there is already widespread support for reducing inequality. According to the Equality Trust, 76% of UK adults agree that large wealth gaps give some people too much political power.

Research by the Sutton Trust finds younger people especially attuned to these disparities: only 21% of 18 to 24-year-olds believe everyone has the same chance to succeed and 57% say it’s harder for their generation to get ahead. Most believe that coming from a wealthy family (75%) and knowing the right people (84%) are key to getting on in life.

In a post-growth world, higher taxes would not only mean wealthier individuals and corporations contributing a relatively greater share, but the wider public shifting consumption patterns, spending less on private goods and more collectively through the state. But the recent example of France shows how challenging this tightope is to walk.

In September 2024, its former prime minister, Michel Barnier, signalled plans for targeted tax increases on the wealthy, arguing these were essential to stabilise the country’s strained public finances. While politically sensitive, his proposals for tax increases on wealthy individuals and large firms initially passed without widespread public unrest or protests.

However, his broader austerity package – encompassing €40 billion (£34.5 billion) in spending cuts alongside €20 billion in tax hikes – drew vocal opposition from both left‑wing lawmakers and the far right, and contributed to parliament toppling his minority government in December 2024.

In the UK, the pressure on government finances (heightened both by Brexit and COVID) has seen a combination of “stealth” tax rises – notably, the ongoing freeze on income tax thresholds, which quietly drags more earners into higher tax bands – and more visible increases, such as the rise in employer National Insurance contributions. At the same time, the UK government moved to cut benefits in its spring statement, increasing financial pressure on lower-income households.

Such measures surely mark the early signs of a deeper financial reckoning that post-growth realities will force into the open: how to sustain public services when traditional assumptions about economic expansion can no longer be relied upon.

For the traditional parties, the political heat is on. Regions most left behind by structural economic shifts are increasingly drawn to populist and anti-establishment movements. Electoral outcomes have shown a significant shift, with far-right parties such as France’s National Rally and Germany’s Alternative for Germany (AfD) making substantial gains in the 2024 European parliament elections, reflecting a broader trend of rising support for populist and anti-establishment parties across the continent.

Voters are expressing growing dissatisfaction not only with the economy, but democracy itself. This sentiment has manifested through declining trust in political institutions, as evidenced by a Forsa survey in Germany where only 16% of respondents expressed confidence in their government and 54% indicated they didn’t trust any party to solve the country’s problems.

This brings us to the central dilemma: can any European politician successfully lead a national conversation which admits the economic assumptions of the past no longer hold? Or is attempting such honesty in politics inevitably a path to self-destruction, no matter how urgently the conversation is needed?

Facing up to a new economic reality

For much of the postwar era, economic life in advanced democracies has rested on a set of familiar expectations: that hard work would translate into rising incomes, that home ownership would be broadly attainable and that each generation would surpass the prosperity of the one before it.

However, a growing body of evidence suggests these pillars of economic life are eroding. Younger generations are already struggling to match their parents’ earnings, with lower rates of home ownership and greater financial precarity becoming the norm in many parts of Europe.

Incomes for millennials and generation Z have largely stagnated relative to previous cohorts, even as their living costs – particularly for housing, education and healthcare – have risen sharply. Rates of intergenerational income mobility have slowed significantly across much of Europe and North America since the 1970s. Many young people now face the prospect not just of static living standards, but of downward mobility.

Effectively communicating the realities of a post-growth economy – including the need to account for future generations’ growing sense of alienation and declining faith in democracy – requires more than just sound policy. It demands a serious political effort to reframe expectations and rebuild trust.

History shows this is sometimes possible. When the National Health Service was founded in 1948, the UK government faced fierce resistance from parts of the medical profession and concerns among the public about cost and state control. Yet Clement Attlee’s Labour government persisted, linking the creation of the NHS to the shared sacrifices of the war and a compelling moral vision of universal care.

While taxes did rise to fund the service, the promise of a fairer, healthier society helped secure enduring public support – but admittedly, in the wake of the massive shock to the system that was the second world war.

Psychological research offers further insight into how such messages can be received. People are more receptive to change when it is framed not as loss but as contribution – to fairness, to community, to shared resilience. This underlines why the immediate postwar period was such a politically fruitful time to launch the NHS. The COVID pandemic briefly offered a sense of unifying purpose and the chance to rethink the status quo – but that window quickly closed, leaving most of the old structures intact and largely unquestioned.

A society’s ability to flourish without meaningful national growth – and its citizens’ capacity to remain content or even hopeful in the absence of economic expansion – ultimately depends on whether any political party can credibly redefine success without relying on promises of ever-increasing wealth and prosperity. And instead, offer a plausible narrative about ways to satisfy our very human needs for personal development and social enrichment in this new economic reality.

The challenge will be not only to find new economic models, but to build new sources of collective meaning. This moment demands not just economic adaptation but a political and cultural reckoning.

If the idea of building this new consensus seems overly optimistic, studies of the “spiral of silence” suggest that people often underestimate how widely their views are shared. A recent report on climate action found that while most people supported stronger green policies, they wrongly assumed they were in the minority. Making shared values visible – and naming them – can be key to unlocking political momentum.

So far, no mainstream European party has dared articulate a vision of prosperity that doesn’t rely on reviving growth. But with democratic trust eroding, authoritarian populism on the rise and the climate crisis accelerating, now may be the moment to begin that long-overdue conversation – if anyone is willing to listen.

Welcome to Europe’s first ‘post-growth’ nation

I’m imagining a European country in a decade’s time. One that no longer positions itself as a global tech powerhouse or financial centre, but the first major country to declare itself a “post-growth nation”.

This shift didn’t come from idealism or ecological fervour, but from the hard reality that after years of economic stagnation, demographic change and mounting environmental stress, the pursuit of economic growth no longer offered a credible path forward.

What followed wasn’t a revolution, but a reckoning – a response to political chaos, collapsing public services and widening inequality that sparked a broad coalition of younger voters, climate activists, disillusioned centrists and exhausted frontline workers to rally around a new, pragmatic vision for the future.

At the heart of this movement was a shift in language and priorities, as the government moved away from promises of endless economic expansion and instead committed to wellbeing, resilience and equality – aligning itself with a growing international conversation about moving beyond GDP, already gaining traction in European policy circles and initiatives such as the EU-funded “post-growth deal”.

But this transformation was also the result of years of political drift and public disillusionment, ultimately catalysed by electoral reform that broke the two-party hold and enabled a new alliance, shaped by grassroots organisers, policy innovators and a generation ready to reimagine what national success could mean.

Taxes were higher, particularly on land, wealth and carbon. But in return, public services were transformed. Healthcare, education, transport, broadband and energy were guaranteed as universal rights, not privatised commodities. Work changed: the standard week was shortened to 30 hours and the state incentivised jobs in care, education, maintenance and ecological restoration. People had less disposable income – but fewer costs, too.

Consumption patterns shifted. Hyper-consumption declined. Repair shops and sharing platforms flourished. The housing market was restructured around long-term security rather than speculative returns. A large-scale public housing programme replaced buy-to-let investment as the dominant model. Wealth inequality narrowed and cities began to densify as car use fell and public space was reclaimed.

For the younger generation, post-growth life was less about climbing the income ladder and more about stability, time and relationships. For older generations, there were guarantees: pensions remained, care systems were rebuilt and housing protections were strengthened. A new sense of intergenerational reciprocity emerged – not perfectly, but more visibly than before.

Politically, the transition had its risks. There was backlash – some of the wealthy left. But many stayed. And over time, the narrative shifted. This European country began to be seen not as a laggard but as a laboratory for 21st-century governance – a place where ecological realism and social solidarity shaped policy, not just quarterly targets.

The transition was uneven and not without pain. Jobs were lost in sectors no longer considered sustainable. Supply chains were restructured. International competitiveness suffered in some areas. But the political narrative – carefully crafted and widely debated – made the case that resilience and equity were more important than temporary growth.

While some countries mocked it, others quietly began to study it. Some cities – especially in the Nordics, Iberia and Benelux – followed suit, drawing from the growing body of research on post-growth urban planning and non-GDP-based prosperity metrics.

This was not a retreat from ambition but a redefinition of it. The shift was rooted in a growing body of academic and policy work arguing that a planned, democratic transition away from growth-centric models is not only compatible with social progress but essential to preventing environmental and societal collapse.

The country’s post-growth transition helped it sidestep deeper political fragmentation by replacing austerity with heavy investment in community resilience, care infrastructure and participatory democracy – from local budgeting to citizen-led planning. A new civic culture took root: slower and more deliberative but less polarised, as politics shifted from abstract promises of growth to open debates about real-world trade-offs.

Internationally, the country traded some geopolitical power for moral authority, focusing less on economic competition and more on global cooperation around climate, tax justice and digital governance – earning new relevance among smaller nations pursuing their own post-growth paths.

So is this all just a social and economic fantasy? Arguably, the real fantasy is believing that countries in Europe – and the parties that compete to run them – can continue with their current insistence on “growth at all costs” (whether or not they actually believe it).

The alternative – embracing a post-growth reality – would offer the world something we haven’t seen in a long time: honesty in politics, a commitment to reducing inequality and a belief that a fairer, more sustainable future is still possible. Not because it was easy, but because it was the only option left.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

![]()

Peter Bloom does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. His latest book is Capitalism Reloaded: The Rise of the Authoritarian-Financial Complex (Bristol University Press).

– ref. Welcome to post-growth Europe – can anyone accept this new political reality? – https://theconversation.com/welcome-to-post-growth-europe-can-anyone-accept-this-new-political-reality-257420