Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Dilara Baysal, Research Fellow in Sociology, Concordia University

As companies face pressure to increase productivity, many are calling workers back to the office — even though there is limited evidence that return-to-office policies actually improve innovation or performance.

In cities like Toronto and Vancouver, where many major companies are headquartered, this is putting pressure on people to live near expensive downtown areas.

As of April 2025, average one-bedroom rents were $2,317 in Toronto and $2,536 in Vancouver, with North Vancouver even higher at $2,680. If return-to-office policies continue, more workers may be forced into these pricey city centres, adding pressure to already overheated housing markets.

Since early 2025, return-to-office policies have added to Canada’s housing stress. The Royal Bank of Canada, for instance, now requires staff in the office four days a week, and Amazon ended remote work in January. While rents haven’t jumped yet, similar policies in the U.S. have already pushed up demand, and may be a sign of what’s to come.

In Washington, D.C., rents rose 3.3 per cent after federal employees were called back to offices. Cities like New York and San Francisco also saw rent increases linked to companies like JPMorgan Chase, Meta and Salesforce reversed remote work policies.

The myth of office productivity

According to the Bank of Canada, Canada’s economy is being negatively affected by low productivity. Low productivity slows Canada’s economic growth and keeps wages low. It also makes inflation worse because supply can’t keep up with demand. A productive economy meets demand more easily, keeping prices stable.

In response, many companies are pushing return-to-office as the answer. RBC CEO Dave McKay endorsed a return to the office back in 2023, saying that “the absence of working together” has hurt innovation and productivity.

At Google, under mounting pressure to compete in artificial intelligence, co-founder Sergey Brin also pushed for full-time office work, calling a 60-hour week the “sweet spot” for productivity.

But recent research shows the story isn’t so simple. A University of Chicago working paper found that strict return-to-office rules can cause senior staff to leave, which hurts innovation.

Read more:

Working one day a week in person might be the key to happier, more productive employees

Another study of 48,000 knowledge workers in India found that hybrid setups — where some people are in the office and others work from home — can make it harder to share ideas and work together.

Meanwhile, a Stanford-led study found that working in the office just two days a week kept productivity strong and cut employee turnover by 33 per cent.

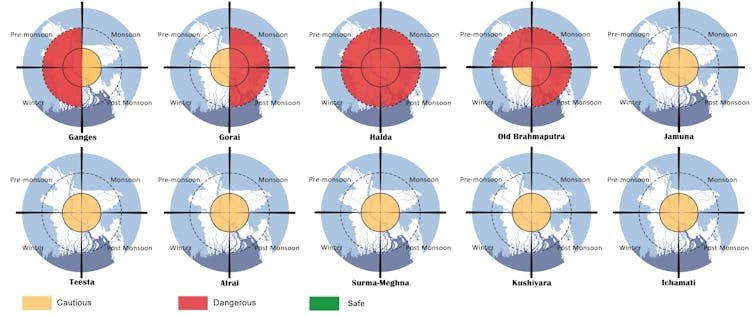

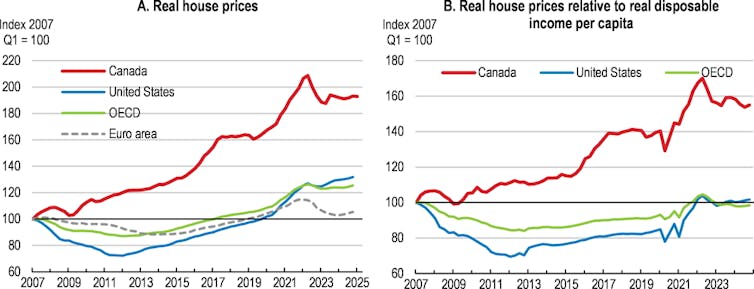

(Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), CC BY

Where people live matters more

Return-to-office mandates also aren’t a guaranteed way to boost productivity. A 2023 study supported by housing organizations across Canada found that affordable, well-located housing helps people find better jobs and specialize in their work.

But when housing costs are high and commutes are long, productivity drops, especially for lower-income workers. Long commutes and high living costs create stress, limit mobility and cause people to miss out on job opportunities.

Studies show that investing in technology and training workers matters much more. Research from the Canadian Research Data Centre Network finds that workplace training improves productivity in most sectors.

A recent report from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation also shows that high housing costs make it harder for many people to live in big cities, which ultimately reduces diversity in the workforce and weakens the economy.

Affordable housing could boost productivity

Housing in Canada is often viewed in two ways. One treats it as a commodity, where prices follow supply and demand. In this view, policies focus on increasing supply and offering market incentives. The other sees housing as a public need and a basic right, and calls for government action to ensure affordability and stability.

Read more:

Housing is both a human right and a profitable asset, and that’s the problem

In practice, market forces can undermine policies designed to meet housing needs and ensure affordability. In Toronto, for example, developers resisted inclusionary zoning rules that require or encourage developers to include a certain percentage of affordable housing units within new residential developments. Instead, they delayed projects or chose to build high-end condos in different zones.

This tension between housing as a commodity and housing as a public good is central to Canada’s current housing strategy. Prime Minister Mark Carney’s government has pledged to build 500,000 new homes annually by 2035 using tools like public lands, modular housing and tax incentives.

While this supply-focused strategy targets long-term housing needs, it must also account for today’s complex economic realities such as inflation, increasing unemployment and economic stagnation due to lagging productiviy.

Without tackling affordability and access directly, building more homes alone won’t be enough.

(Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), CC BY

The real foundation of a productive economy

Return-to-office policies often focus too much on one thing: how much each worker produces. But that narrow view of productivity ignores what really supports good work: access to affordable housing, time for training and flexibility to relocate for better job opportunities.

To address productivity challenges, companies should invest in job-specific training, digital skills and ongoing learning to help employees adapt to new tools and processes, and the should offer more flexibility. What workers need most are affordable homes, shorter commutes and real opportunities to grow — not added stress and rising costs.

![]()

Dilara Baysal does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Returning to the office isn’t the answer to Canada’s productivity problem — and it will add pressure to urban housing – https://theconversation.com/returning-to-the-office-isnt-the-answer-to-canadas-productivity-problem-and-it-will-add-pressure-to-urban-housing-260395