Source: The Conversation – UK – By John Dearing, Emeritus Professor of Physical Geography, University of Southampton

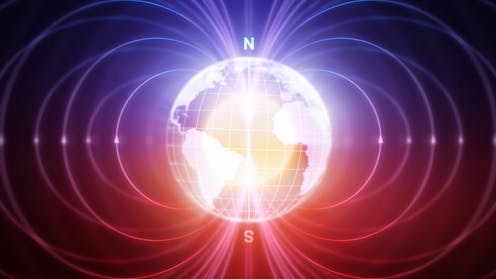

Some of Earth’s largest climate systems may collapse not with a bang, but with a whimper. Surprisingly, experiments with magnets are helping us understand how.

We now widely accept that greenhouse gases and the way we use natural resources are putting enormous stress on the world’s climate and ecosystems. It’s also well known that even small increases in stress can push Earth systems, like rainforests, ice sheets or ocean currents, past tipping points, leading to major and often irreversible changes.

But there’s a lot we still don’t know about tipping points. When might they happen? What will they look like? And what should we do about them?

Some local tipping points have already been reached. For example, many lakes have abruptly shifted in the past few decades from clear water to slimy, algae-choked pools, usually in response to fertilisers running off nearby farmland.

Janet J / shutterstock

For larger systems, like the entire Amazon forest or the West Antarctic ice sheet, the longer timescales involved mean direct observation – and certainly experiments – are impossible.

But we can look for clues elsewhere. In fact, we can now learn about tipping points from something much smaller and far more controllable: magnets.

Magnets have tipping points too

In our recent research, we used magnetic materials to mimic the behaviour of an ecosystem stressed by global warming. Just like Earth’s climate systems, magnets can tip from one stable state to another – flipping from positive to negative – when pushed hard enough.

We found that magnets don’t all flip the same way. Some shift abruptly – a characteristic of many hard materials. Others shift smoothly and more easily – as commonly found with soft magnets.

Whether a magnet collapses abruptly or smoothly is determined by its structure. As a general rule, hard materials are simple structures that absorb stress up to a point and then suddenly flip – much like a small, well-mixed lake that stays clear until one day, when enough fertiliser has leaked in, it turns green and slimy almost overnight.

Soft magnets, on the other hand, are more complex inside. Different parts respond to stress at different rates. This is similar to a large forest, where some species can handle rising temperatures but others are less resilient.

The result is a reorganisation. Some species die out, others take over, and the whole system gradually transitions into a different type of forest – or even into a new ecosystem like a grassland.

Steve Allen / shutterstock

The same principles may apply beyond biology. Ocean currents and ice sheets with their many varied and moving parts might also behave like soft magnets, reorganising gradually rather than collapsing in one sudden movement.

Softer systems are easier to flip back

Our experiments with magnets uncovered something else with implications for Earth’s climate systems and their tipping points.

The softer a system is, the easier it is to reverse the change – but only if you act before the stress builds up. If the pressure has built up too much, even soft systems start behaving like hard ones, flipping suddenly and dramatically.

We also found that what may look like a soft and complex system – a whole rainforest or ice sheet, for instance – can be made up of lots of smaller hard elements. Each of these elements has its own sensitivity to a specific level of stress. Zoom in far enough, and you’ll see many more abrupt tipping points at the level of a single lake or patch of trees.

This matters because the speed of change is just as important as the amount. In magnets, the faster we applied stress, the more likely they were to tip suddenly. Climate systems seem to behave the same way: the faster we heat the world, the greater the risk of sudden collapse.

If we see these big complex systems slowly shifting and think there’s still time to act – we may be wrong. Like the proverbial frogs in boiling water, we may not notice we have passed the point of no return until it is too late.

This is why we must watch closely, especially at the local level, for any warning signs. A patch of wetland drying out or a small tract of forest dying back. These might seem like small changes, but they may signal a much larger decline is already underway.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

John Dearing is a member of the Green Party of England and Wales.

Roy Thompson and Simon Willcock do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Gradual v sudden collapse: what magnets teach us about climate tipping points – https://theconversation.com/gradual-v-sudden-collapse-what-magnets-teach-us-about-climate-tipping-points-258606