Source: – By Agnes Mueller, Carol Kahn Strauss Fellow in Jewish Studies at the American Academy in Berlin, Professor of German and American Literature, University of South Carolina

The consequences of Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, attack and Israel’s war in Gaza have reverberated far beyond the zones of conflict.

In the United States, for example, a growing number of people, including some Jewish groups, assert that political leaders are exploiting concerns about antisemitism for their own political goals, from cracking down on academic freedom to deporting pro-Palestinian activists.

Debate about the war in Gaza feels fraught in Germany, too, where concerns about rising antisemitism have been used to criticize some Muslim communities. The Holocaust looms over discussions about Israel, with many claiming the country’s sense of historical guilt has made it, until recently, reluctant to criticize Israeli politics.

In the wake of the country’s reunification in the early 1990s, about 200,000 Jews from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union came to Germany. In more recent years, waves of predominantly Muslim refugees from the Middle East have entered a space that already had a large population of Turkish immigrants and their descendants. However, many Germans oppose these more open immigration policies, with widespread backlash against Muslim migrants.

In recent decades, some of Germany’s migrants and their children – some Jewish, and some Muslim – have used fiction to explore their identity and these contested issues in new ways, challenging simple narratives. As a scholar of German literature and Jewish studies, I have studied how literature creates new spaces for readers to explore the similarities between their experiences, building solidarity beyond stereotypes.

‘The Prodigal Son’

Many of today’s young Jewish writers were born in the former Soviet Union and arrived in Germany with their parents as part of the “quota refugee” program. Initiated in the early 1990s, this program invited Jewish migrants into a newly unified Germany – intended to show that the country was taking responsibility for the atrocities of the past. The newcomers were flippantly called “Wiedergutmachungsjuden,” “make-good-again Jews,” referring to Germans’ desire to atone.

One of them was Olga Grjasnowa. Born in 1984, Grjasnowa came from Azerbaijan to Germany at age 11. She has written about Holocaust memory, as in her 2012 novel “All Russians Love Birch Trees,” and said in a 2018 interview that all her books are “Jewish books.”

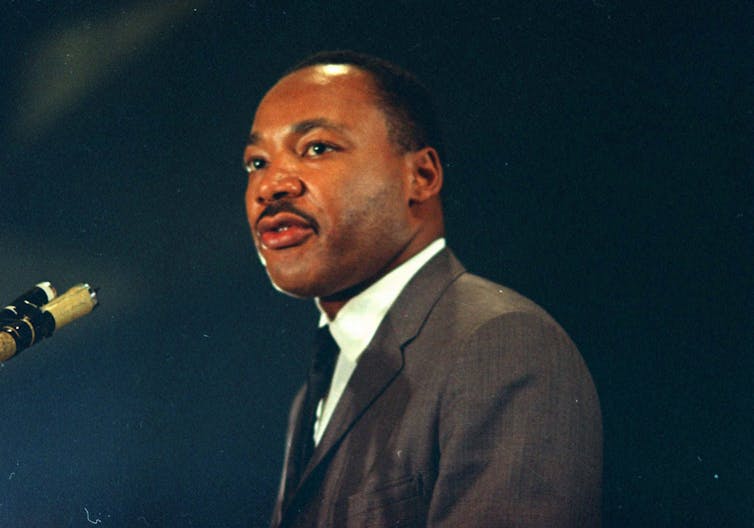

Roberto Ricciuti/Getty Images

Her 2021 book “Der verlorene Sohn,” “The Prodigal Son,” echoes Holocaust memory, but in a historical novel set in 19th-century Russia.

The protagonist Jamaluddin – the name derives from the Arabic word for “beauty of the faith” – is born in the Caucasian region of Dagestan, as the son of a powerful Muslim imam. To negotiate a peace deal, the boy is given as a hostage to Russia, where he grows up in the Orthodox Christian court of the czar. Though initially treated as an outsider, Jamaluddin assimilates and becomes a high-ranking officer, a life that ends when he must return to Dagestan. But there, too, he now feels homeless, regarded with suspicion as a stranger.

“The Prodigal Son” deals with abduction, deportation, exile and constant wandering. Jamaluddin’s fate is shaped by authoritarianism, repression, war and discrimination – themes that are familiar in Holocaust literature, though here they befall a Muslim boy in another time and place.

Repeatedly, the novel makes mention of Jewish communities and their own suffering under the czar. As Jewish boys are being forced to march from remote villages to Saint Petersburg, Jamaluddin is “furious and ashamed” of his fellow officers. But he also begins to feel self-pity, flooded with memories of his own departure from home.

This scene depicts a historical reality under Czar Nicholas I, who ruled from 1825-1855: Russian Jewish boys were conscripted, sometimes kidnapped, to serve in the army. For contemporary audiences, the description can also evoke the death marches of Jewish prisoners during the Shoah, the Hebrew term for the Holocaust. Several additional moments in the book connect Jamaluddin’s experiences with images of Jewish flight and expulsion.

New conversations

Jamaluddin’s fate as an outsider between cultures can also bring to mind migrants’ experiences and emotions today. In 2022, one-quarter of Germans were either migrants themselves or had a parent who was not born in Germany. The largest minority group are Muslim-born Germans of Turkish descent, who are still routinely discriminated against.

Antisemitism, meanwhile, is pervasive but less obvious. The Germans’ relationship with Jews was long dominated by silence and guilt – and Jews themselves were mostly invisible until the end of the Cold War, when Jewish migration from the former Soviet states picked up. My 2015 book “The Inability to Love” describes how mainstream German authors, fueled by guilt and shame over the Nazi past, fell into a philosemitic antisemitism: Outward displays of repentance for the Holocaust and public policies that ostensibly embraced Jews clashed with privately held prejudice.

Many examples of new German literature show contemporary Jewish and Muslim characters with complex identities – protagonists who are not seen as simply Jewish, Muslim or belonging to only one culture, pushing back on reductive stereotypes.

For example, Kat Kaufmann’s 2015 novel “Superposition” tells the story of the young, popular and charismatic Izy, a Russian Jew who lives in Berlin as a jazz pianist. Her love interest is Timur, an Eastern European man with a typically Muslim name. When Izy thinks of her and Timur’s future son, she imagines him growing up with the luxury to conceal where he is from – to define his identity as he wishes, unlike previous generations.

Oliver Berg/picture alliance via Getty Images

Stories by novelists such as Dmitrij Kapitelman, Lena Gorelik, Marina Frenk and Dana Vowinckel also depict moments of connection between Jews and other Germans, or between Jews and Muslims.

Turkish and/or Muslim writers such as Fatma Aydemir and Nazlı Koca – who now lives in America, writing in English – tell similar stories of young characters navigating German culture as marginalized individuals. They often depict young women who struggle to reconcile their culture of origin with German social expectations and xenophobia today.

“I wanted to question the idea that we all have one single identity and that’s it,” Aydemir told the literary site K24 about her novel “Ellbogen,” whose protagonist finds herself fleeing to Turkey, her family’s original home, after a personal crisis. “I think things are way more complex, more fluid than most of us want to believe.”

This younger generation of German Jewish and Muslim writers is recasting entrenched debates, showing characters whose identities are multidimensional and more open than the burdened past or fraught present politics would suggest. Today’s young writers are creating new, brave spaces for conversation and empathy.

![]()

Agnes Mueller does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Germany’s young Jewish and Muslim writers are speaking for themselves – exploring immigrant identity beyond stereotypes – https://theconversation.com/germanys-young-jewish-and-muslim-writers-are-speaking-for-themselves-exploring-immigrant-identity-beyond-stereotypes-252968