Source: The Conversation – (in Spanish) – By Zaradat Domínguez Galván, Profesora de Literatura, Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria

Cuando preguntamos quién fue el primer autor literario de la historia, muchos piensan en Homero. La imagen del poeta ciego de la Antigua Grecia suele ocupar el podio de la tradición literaria occidental.

Pero lo cierto es que debemos mirar mucho más atrás, más allá de Grecia, más allá incluso del alfabeto, y dirigir nuestros ojos hacia el origen mismo de la escritura: la antigua Mesopotamia. Allí, hace más de 4 000 años, una mujer firmó su obra con su propio nombre: Enheduanna.

¿Quién fue Enheduanna?

Enheduanna vivió alrededor del año 2 300 a. e. c., en la ciudad de Ur, lo que hoy es el sur de Irak. Su figura destaca por varios motivos: fue suma sacerdotisa del dios lunar Nanna, lo cual le confirió un gran poder político y religioso. Además, fue hija del rey Sargón de Akkad, fundador del primer imperio mesopotámico, y, sobre todo, autora de una obra literaria de profundo contenido teológico, político y poético.

“Enheduanna” no era su identificación personal, sino un título religioso que podría traducirse como “alta sacerdotisa, ornamento del cielo”. Su verdadero nombre sigue siendo un misterio. Lo que no se discute es su impacto: Enheduanna escribió, firmó y dejó constancia de su autoría, lo que la convierte en la primera persona, hombre o mujer, que conocemos por haber hecho esto.

Escritura, poder y espiritualidad

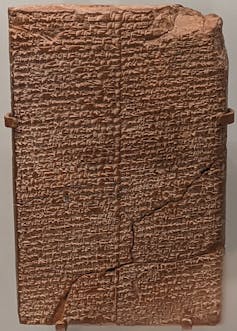

La escritura cuneiforme ya existía desde mediados del cuarto milenio antes de nuestra era. Había surgido como una herramienta administrativa, útil para llevar registros económicos, controlar impuestos o contabilizar ganado. Sin embargo, hacia la época de Enheduanna, había empezado a emplearse también para expresar ideas religiosas, filosóficas y estéticas. Era un arte sagrado, vinculado a la diosa Nisaba, patrona de los escribas, el grano y el conocimiento.

En este contexto, la figura de esta autora es especialmente reveladora. Su obra combina una profunda devoción religiosa con un mensaje político claro. Su poesía se enmarca en una estrategia imperial: legitimar la dominación de Akkad sobre las ciudades sumerias mediante un lenguaje común, una fe compartida y un discurso teológico unificado.

Una obra de alto vuelo

De Enheduanna se conservan varias composiciones, entre las que destacan:

-

Exaltación de Inanna: un largo himno en el que ensalza a la diosa del amor y la guerra, Inanna, pidiéndole ayuda en tiempos de exilio. Se considera su obra más personal y poderosa.

-

Los himnos del templo: un conjunto de 42 himnos dedicados a distintos templos y divinidades de Sumer. Aquí, Enheduanna construye un mapa espiritual del territorio, exaltando la conexión entre religión y poder político.

-

Otros himnos fragmentarios, entre ellos uno dedicado a su dios Nanna.

Estos ejemplos no son simples textos religiosos: están estructurados con gran sofisticación, cargados de simbolismo, emoción y visión política. En ellos, Enheduanna aparece como mediadora entre dioses y humanos; entre su padre, el emperador, y las ciudades conquistadas.

¿Por qué no la conocemos?

Resulta chocante que Enheduanna no figure en los manuales escolares ni en la mayoría de cursos universitarios de literatura. Pocas personas fuera de los estudios de historia antigua o de género han oído hablar de ella.

Masha Stoyanova/Penn Museum

Es lícito preguntarse si el olvido de Enheduanna responde a una invisibilización sistémica de las mujeres en la historia cultural. Como apunta la historiadora del arte Ana Valtierra Lacalle, durante siglos se ha negado la presencia de mujeres escribas o artistas en la Antigüedad, a pesar de las evidencias arqueológicas que prueban que sabían leer, escribir y administrar recursos.

Enheduanna no fue una anomalía aislada: su existencia demuestra que las mujeres participaron activamente en el desarrollo de la civilización mesopotámica, tanto en la esfera religiosa como intelectual. El hecho de que ella fuera la primera persona en firmar un texto con su nombre debería tener el lugar que merece en la historia de la humanidad.

Enheduanna representa no solo un hito literario, sino también un símbolo poderoso de la capacidad de las mujeres para crear, pensar y liderar desde el origen mismo de la cultura escrita. Su voz resuena desde las tablillas de arcilla con una fuerza que atraviesa los milenios, puesto que con ella la historia comienza no solo con palabras, sino con una voz, con una experiencia subjetiva y con una conciencia autorreflexiva del acto de escribir que no debería pasar desapercibida.

![]()

Zaradat Domínguez Galván no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

– ref. La primera persona que firmó una obra literaria fue una mujer: Enheduanna – https://theconversation.com/la-primera-persona-que-firmo-una-obra-literaria-fue-una-mujer-enheduanna-267800