Source: The Conversation – (in Spanish) – By Manuel Torres Aguilar, Catedrático de Historia del Derecho y de las Instituciones y director de la Cátedra UNESCO de Resolución de Conflictos, Universidad de Córdoba

Está de moda estos días escribir sobre la Doctrina Monroe, formulada en 1823 por James Monroe, el quinto presidente de los Estados Unidos, que advertía contra la colonización o intervención las nuevas naciones americanas y proclamaba: “América para los americanos”. Y hay motivos para ello.

La extracción del presidente venezolano Nicolás Maduro por parte de fuerzas especiales estadounidenses el 3 de enero de 2026 es una nueva fase de la vieja doctrina Monroe. Ahora, esta política exterior se enmarca en el reposicionamiento geoestratégico estadounidense para hacerse de nuevo con el control de su región y, sobre todo, para que el petróleo venezolano no siga fluyendo hacia Rusia y China.

Espíritu expansionista

Tras la independencia de sus trece colonias fundacionales, en 1770, Estados Unidos tuvo la necesidad de un espacio de influencia que garantizase el futuro expansionista de un proyecto político que iba más allá de la separación de Inglaterra.

Si en un principio no hubo un afán imperialista, poco después comenzó la ocupación de tierras para la agricultura, ganando territorios a los indígenas (y también a los colonizadores franceses). La acumulación de capital, la naciente industrialización y la doctrina del “Destino manifiesto” (que les faculta para ir ganando terreno al oeste de su territorio) fructifican y fortalecen un ideal de expansión constante.

Luego, la debilidad institucional, social y política de México permitió la colonización de Texas, California y otros territorios del antiguo virreinato de Nueva España por parte de Estados Unidos.

Imperialismo estadounidense en América

El relato imperialista de EE. UU. ha ido cambiando con el discurrir de la historia. Un argumento útil para expoliar a México a principios del XIX fue la defensa de los derechos de sus colonos y del libre comercio. El marco doctrinal formulado inicialmente por Monroe pretendía el “noble” objetivo de evitar que las potencias europeas mantuviesen su hegemonía en la región, una vez desaparecido el dominio colonial.

Nada más loable que dejar que los países americanos rigiesen su nuevo futuro. Pero, en ese escenario, las islas de Cuba, Puerto Rico y Filipinas seguían representando la presencia europea en lo que ya Estados Unidos consideraba su espacio vital.

La guerra hispano-estadounidense de 1898, a cuenta de la independencia de Cuba, marcó el fin del siglo XIX. Si ya entonces Estados Unidos se postulaba como candidato al dominio global, aún debía demostrar su control sobre su espacio circundante. La presunta independencia de Cuba fue un primer ejemplo de control político e institucional sobre un país a través de sus instituciones y de su propia Constitución.

Ocho años después del estallido de la guerra de independencia de Cuba, la situación política de la isla no era del todo favorable a las aspiraciones estadounidenses y por ello la ocuparon nuevamente. En ese mismo período, apoyaron que Panamá, entonces un departamento colombiano, se separase de Colombia. Así favorecieron la construcción del canal bajo su hegemonía.

En 1916, y hasta 1924, ocuparon militarmente la República Dominicana con el argumento del incumplimiento de pagos. El objetivo real era sofocar un movimiento insurgente que pretendía establecer un régimen fuera del control comercial y político de EE. UU. Los marines estadounidenses volverían en 1965, tras el asesinato del dictador Trujillo, para garantizar la estabilidad del país.

De nuevo la protección de sus intereses y ahuyentar la influencia europea sirvieron de excusa para ocupar militarmente Haití desde 1915 hasta 1934, y Nicaragua desde 1912 hasta 1933, con el objetivo de proteger un presunto proyecto de canal.

Tras este período de intenso intervencionismo militar en “la América para los americanos”, vino un cierto relajamiento ocasionado por la participación estadounidense en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.

Imperialismo en tiempos de Guerra Fría

La Guerra Fría abrió una nueva etapa en la que mostrar la hegemonía estadounidense en su “patio trasero”. En 1954, Jacobo Árbenz, presidente democráticamente elegido en Guatemala, propició una reforma agraria contraria a los intereses de la United Fruit Company. Ese fue motivo suficiente para declararlo comunista y apoyar un golpe de estado orquestado por la CIA.

En 1961, grupos de cubanos exiliados, armados por el gobierno de Estados Unidos, intentaron invadir la isla desembarcando en Bahía de Cochinos. Aunque fue un sonoro fracaso, la invasión supuso un nuevo empuje a la política intervencionista estadounidense en América Latina, con el argumento de proteger sus intereses y evitar el comunismo cerca de sus fronteras.

Cuatro años después (1965) se produjo una nueva invasión militar en República Dominicana para evitar el triunfo de la izquierda.

Sin necesidad de ocupación militar, pero con el apoyo estratégico de una parte del ejército de Chile, encabezado por el general Augusto Pinochet, en 1973 se puso fin al gobierno democrático de Salvador Allende. El argumento fue, de nuevo, el peligro del triunfo del marxismo en la región, aunque otro objetivo claro era la protección de los intereses sobre el cobre de las empresas mineras estadounidenses.

Diez años después, en 1983, de nuevo el riesgo del marxismo sirvió como argumento para invadir la isla caribeña de Granada.

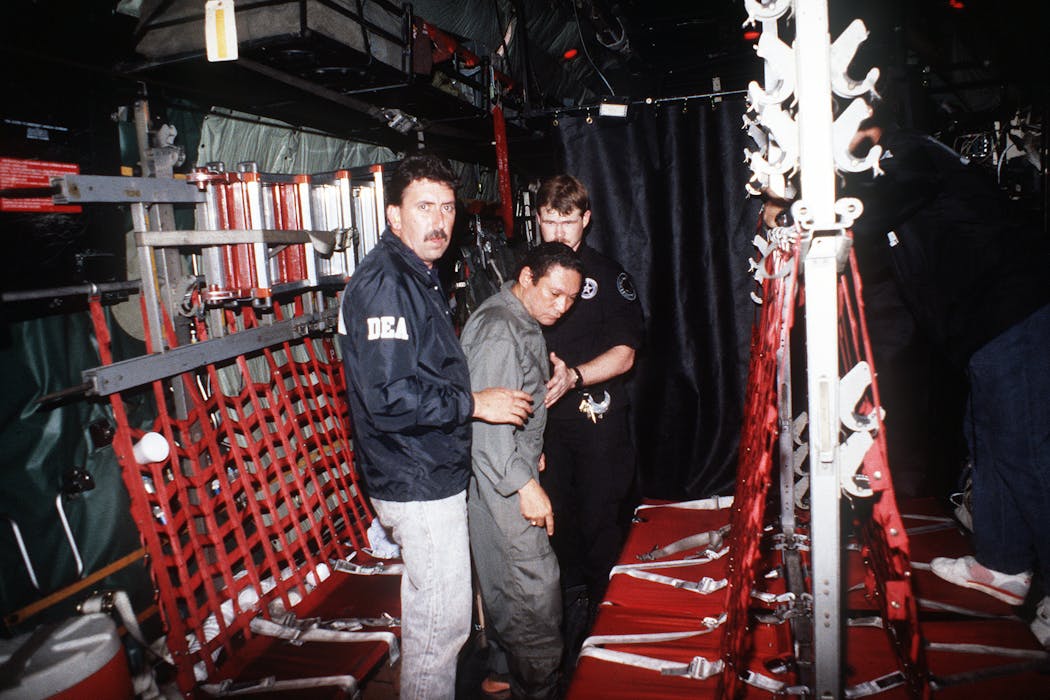

El colofón del siglo XX lo marcó la invasión a Panamá (Operación Causa Justa, 1989) con el objetivo de acabar con el dictador Manuel Noriega, al que EE. UU. acusaba de favorecer el nacotráfico.

A estas intervenciones directas habría que añadir otras más taimadas, pero no menos evidentes: desde el apoyo a las dictaduras del Cono Sur en los setenta y los ochenta, al de los gobiernos autoritarios de Centroamérica durante sus guerras civiles en ese mismo periodo.

¿Por qué Venezuela ahora?

Cabe preguntarse por qué Estados Unidos ha tolerado un régimen dictatorial en Venezuela durante apenas un cuarto de siglo mientras que Cuba va ya para más de sesenta años de bloqueo sin una intervención militar directa. Podría decirse que durante la Guerra Fría no era posible. Pero ¿y después? La respuesta: Cuba no tiene petróleo.

Leer más:

Venezuela o la maldición de los recursos naturales

A estas alturas ya nadie cree que la defensa de la democracia y los derechos humanos sean el eje vertebrador de estas acciones. Si así fuera, hay muchos otros países con sus derechos mermados. Sin embargo, sus regímenes no solo son legitimados sino que, además, participan en acuerdos económicos, militares y políticos con los Estados Unidos de Norteamérica.

![]()

Manuel Torres Aguilar no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

– ref. Los antecedentes en América Latina del ataque estadounidense a Venezuela – https://theconversation.com/los-antecedentes-en-america-latina-del-ataque-estadounidense-a-venezuela-272662