Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By R. Evan Ellis, Senior Associate, Americas Program, The Center for Strategic and International Studies

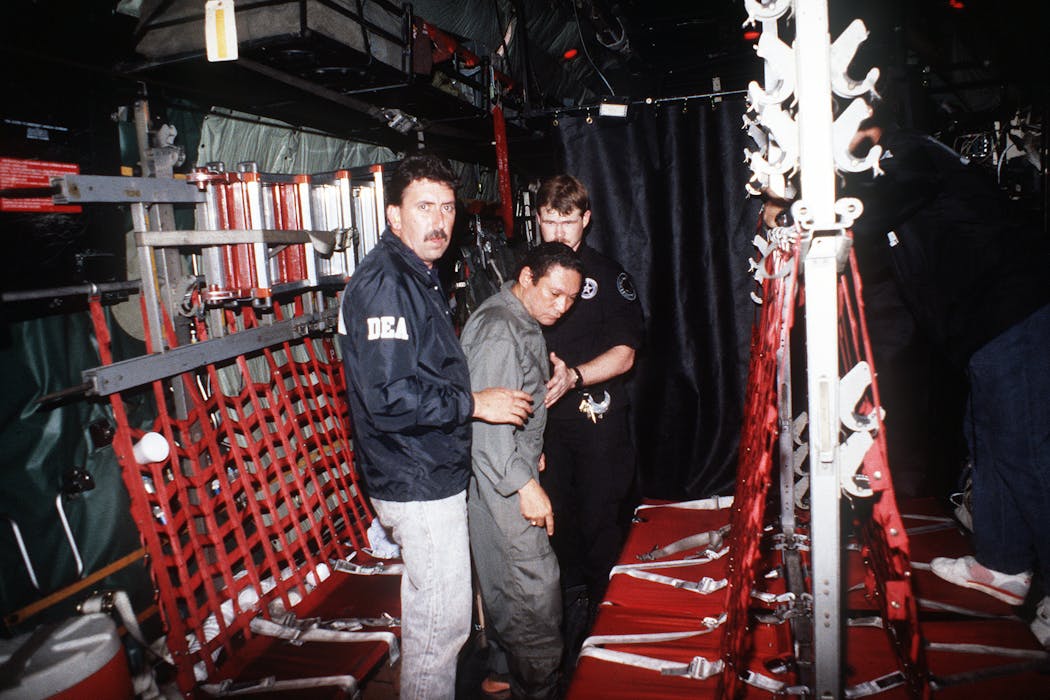

The predawn seizure of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro on Jan. 3, 2026 was a complicated affair. It was also, operationally, a resounding success for the U.S. military.

Operation Absolute Resolve achieved its objective of seizing Maduro through a mix of extensive planning, intelligence and timing. R. Evan Ellis, a military strategist and former Latin America policy adviser to the U.S. State Department, walked The Conversation through what is publicly known about the planning and execution of the raid.

How long would this op have been in the works?

Operation Absolute Resolve was some months in the planning, as the Pentagon acknowledged in its briefing on Jan. 3. My presumption is that from the beginning of the U.S. military buildup in the Caribbean and the establishment of Joint Task Force Southern Spear in the fall, military planners were developing options for the president to capture or eliminate Maduro and other key Chavista leadership, should coercive efforts at persuading a change in the Venezuelan situation fail.

Truth Social

Prior to Southern Spear, U.S. military activities in the region were directly overseen by Southern Command – the part of the Department of Defense responsible for Central America, South America and most of the Caribbean. But establishing a dedicated joint task force in October 2025 helped facilitate the coordination of a large operation, like the one conducted to seize Maduro.

Planning for the Jan. 3 operation likely became more detailed and realistic as the administration settled on a concrete set of options. U.S. forces practiced the raid on a replica of the presidential compound. “They actually built a house which was identical to the one they went into with all the same, all that steel all over the place,” President Donald Trump told “Fox & Friends Weekend.”

Why did the US choose to act now?

The buildup had been going on for months, and the arrival of the USS Gerald R. Ford in November was a key milestone. That gave the U.S. the capability to launch a high volume of attacks against land targets and added to the already huge array of American military hardware stationed in the Caribbean.

It joined an Iwo Jima Amphibious Ready Group, which included a helicopter dock ship and two landing platform vessels. An additional six destroyers and two cruisers were stationed in the region with the capability of launching hundreds of missiles for both land attack and air defense, as well as a special operations mother ship.

Trump’s authorization of CIA operations in Venezuela was probably also a key factor. It is likely that individuals inside Venezuela played invaluable roles not only in obtaining intelligence, but also in cooperating with key people in Maduro’s military and government to make sure they did – or did not do – certain things at key moments during the Jan. 3 operation.

With the complex array of plans and preparations in place by December, the U.S. military was likely ready to execute, but it had to wait for opportune conditions to maximize the probability of success.

What constitutes the opportune moment?

There are arguably three things needed for the opportune moment: good intelligence, the establishment of reliable cooperation arrangements on the ground, and favorable tactical conditions.

Intel would have been crucial. Trump acknowledged his authorization of covert CIA operations in Venezuela in October, and evidently, by the end of the year, analysts had gathered the information needed to make this operation go smoothly. The intelligence would have had to include knowing exactly where Maduro would be at the time of the operation, and the situation around him.

Over the past few months, according to media reporting, the intelligence community had agents on the ground in Venezuela, likely having conversations with people in the military, the Chavista leadership and beyond, who had crucial information or whose behavior was relevant to different parts of the operation – such as perhaps shutting down a system, standing down a military unit or being absent from a post at a key moment. A report from The New York Times indicates that the U.S. had a human source close to Maduro who was able to provide details of his day-to-day life, down to what he ate.

The more tactical conditions that were needed for the opportune moment involved things like the weather – you didn’t want storms or high winds or cloud cover that would put U.S. aircraft in danger as they flew in some very treacherous low-level routes through the mountains that separate Fort Tiun – the military compound in Caracas where Maduro was captured – from the coast.

How did the operation unfold?

Gen. Dan Caine, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has given some details about how the plan was executed.

We know the U.S. launched aircraft from multiple sites – the operation involved at least 20 different launch sites for 150 planes and helicopters. These would have involved aircraft for jamming operations, some surveillance, fighter jets to strike targets, and some to provide an escort for the helicopters bringing in a special forces unit and members of the FBI.

Jesus Vargas/Getty Images

As an integral part of the operation, the U.S. carried out a series of cyber activities that may have played a role in undermining not only Venezuela’s defense systems, but also its understanding of what was going on. Although the nature of U.S. cyber activities is only speculation here, a coherent, alerted Venezuelan command and control system could have cost the lives of U.S. force members and given Maduro time to seal himself in his safe room, creating a problem – albeit not an insurmountable one – for U.S. forces.

There was also, according to Trump, a U.S.-generated interruption to some part of the power grid. In addition, it appears that there may have been diversionary strikes in other parts of the country to give a false impression to the Venezuelan military that U.S. military activity was directed toward some other, lesser land target, as had recently been the case.

U.S. aircraft then basically disabled Venezuelan air defenses.

As U.S. rotary wing and other assets converged on the target in Caracas – with cover from some of the most capable fighters in the U.S. inventory, including F-35s and F-22s, as well as F-18s – other U.S. assets decimated the air defense and other threats in the area.

It would be logical if elite members of the U.S. 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment were used in the approach to the compound in Caracas. Their skills would have been required if, as I presume, they came in via the canyon route that separates Caracas from the coast. I have driven the road through those mountains, and it is treacherous – especially for an aircraft at low altitude.

Once the team landed, it would have have taken a matter of minutes to infiltrate the compound where Maduro was.

Any luck involved?

According to Trump, the U.S. team grabbed Maduro just as he was trying to get into his steel vault safe room.

“He didn’t get that space closed. He was trying to get into it, but he got bum-rushed right so fast that he didn’t get into that,” the U.S. president told Fox & Friends Weekend.

Although the U.S. was reportedly fully prepared for that eventuality, with high-power torches to cut him out, that delay could have cost time and possibly lives.

It was thus critical to the U.S. mission that forces were able to enter the facility, reach and secure Maduro and his wife in a minimal amount of time.

![]()

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the Department of Defense or the US government.

– ref. How Maduro’s capture went down – a military strategist explains what goes into a successful special op – https://theconversation.com/how-maduros-capture-went-down-a-military-strategist-explains-what-goes-into-a-successful-special-op-272671