Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By James Trapani, Associate Lecturer of History and International Relations, Western Sydney University

After US special forces swooped into Caracas to seize Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and topple his government, US President Donald Trump said the United States will now “run” Venezuela, including its abundant oil resources.

US companies were poised to invest billions to upgrade Venezuela’s crumbling oil infrastructure, he said, and “start making money for the country”. Venezuela has the world’s largest oil reserves – outpacing Saudi Arabia with 303 billion barrels, or about 20% of global reserves.

If this does eventuate – and that’s a very big “if” – it would mark the end of an adversarial relationship that began nearly 30 years ago.

Yes, the Trump administration’s military action in Venezuela was in many ways unprecedented. But it was not surprising given Venezuela’s vast oil wealth and the historic relations between the US and Venezuela under former President Hugo Chávez and Maduro.

A long history of US investment

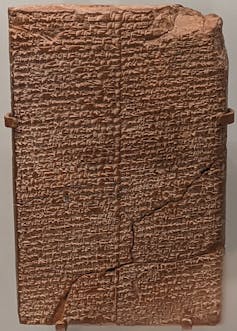

Venezuela is a republic of around 30 million people on the northern coast of South America, about twice the size of California. During much of the early 20th century, it was considered the wealthiest country in South America due to its oil reserves.

Wikimedia Commons

Foreign companies, including those from the US, invested heavily in the growth of Venezuelan oil and played a heavy hand in its politics. In the face of US opposition, however, Venezuelan leaders began asserting more control over their main export resource. Venezuela was a key figure in the formation of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1960, and it nationalised much of its oil industry in 1976.

This negatively impacted US companies like ExxonMobil and has fuelled the recent claims by the Trump administration that Venezuela “stole” US oil.

Economic prosperity, however, did not follow for most Venezuelans. The mismanagement of the oil industry led to a debt crisis and International Monetary Fund (IMF) intervention in 1988. Caracas erupted in protests in February 1989 and the government sent the military to crush the uprising. An estimated 300 people were killed, according to official totals, but the real figure could be 10 times higher.

In the aftermath, Venezuelan society became further split between the wealthy, who wanted to work with the US, and the working class, who sought autonomy from the US. This division has defined Venezuelan politics ever since.

Chávez’s rise to power

Hugo Chávez began his career as a military officer. In the early 1980s, he formed the socialist “Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement-200” within the army and began giving rousing lectures against the government.

Then, after the 1989 riots, Chávez’s recruitment efforts increased dramatically and he began planning the overthrow of Venezuela’s government. In February 1992, he staged a failed coup against the pro-US president, Carlos Andrés Pérez. While he was imprisoned, his group staged another coup attempt later in the year that also failed. Chavez was jailed for two years, but emerged as the leading presidential candidate in 1998 on a socialist revolutionary platform.

Chávez became a giant of both Venezuelan and Latin American politics. His revolution evoked the memory of Simón Bolívar, the great liberator of South America from Spanish colonialism. Not only was Chávez broadly popular in Venezuela for his use of oil revenue to subsidise government programs for food, health and education, he was well-regarded in like-minded regimes in the region due to his generosity.

Most notably, Chávez provided Cuba with billions of dollars worth of oil in exchange for tens of thousands of Cuban doctors working in Venezuelan health clinics.

He also set a precedent of standing up to the US and to the IMF at global forums, famously calling then-US President George W Bush “the devil” at the UN General Assembly in 2006.

US accused of fomenting a coup

Unsurprisingly, the US was no fan of Chávez.

After hundreds of thousands of opposition protesters took to the streets in April 2002, Chavez was briefly ousted in a coup by dissident military officers and opposition figures, who installed a new president, businessman Pedro Carmona. Chávez was arrested, the Bush administration promptly recognised Carmona as president, and the The New York Times editorial page celebrated the fall of a “would-be dictator”.

Chavez swept back into power just two days later, however, on the backs of legions of supporters filling the streets. And the Bush administration immediately faced intense scrutiny for its possible role in the aborted coup.

While the US denied involvement, questions lingered for years about whether the government had advance knowledge of the coup and tacitly backed his ouster. In 2004, newly classified documents showed the CIA was aware of the plot, but it was unclear how much advance warning US officials gave Chavez himself.

US pressure continues on Maduro

Maduro, a trade unionist, was elected to the National Assembly in 2000 and quickly joined Chávez’s inner circle. He rose to the office of vice president in 2012 and, following Chávez’s death the following year, won his first election by a razor-thin margin.

But Maduro is not Chávez. He did not have the same level of support among the working class, the military or across the region. Venezuela’s economic conditions worsened and inflation skyrocketed.

And successive US administrations continued to put pressure on Maduro. Venezuela was hit with sanctions in both the Obama and first Trump presidency, and the US and its allies refused to recognise Maduro’s win in the 2018 election and again in 2024.

Isolated from much of the world, Maduro’s government became dependent on selling oil to China as its sole economic outlet. Maduro also claims to have thwarted several coup and assassination attempts allegedly involving the US and domestic opposition, most notably in April 2019 and May 2020 during Trump’s first term.

US officials have denied involvement in any coup plots; reporting also found no evidence of US involvement in the 2020 failed coup.

Now, Trump has successfully removed Maduro in a much more brazen operation, with no attempts at deniability. It remains to be seen how Venezuelans and other Latin American nations will respond to the US actions, but one thing is certain: US involvement in Venezuelan politics will continue, as long as it has financial stakes in the country.

![]()

James Trapani does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Before toppling Maduro, the US spent decades pressuring Venezuelan leaders over its oil wealth – https://theconversation.com/before-toppling-maduro-the-us-spent-decades-pressuring-venezuelan-leaders-over-its-oil-wealth-272679