Source: The Conversation – in French – By Florence Peteers, MCF Didactique des mathématiques, CY Cergy Paris Université

Si les mathématiques sont unanimement considérées comme décisives dans notre société, elles suscitent nombre de craintes chez les élèves. Les rendre plus accessibles suppose donc de changer leur enseignement. Mais comment ? Le succès de situations « adidactiques » offre quelques pistes à la recherche. Explications.

Parus en décembre 2025, les résultats de la grande consultation nationale sur la place des mathématiques lancée par le CNRS montrent que beaucoup de Français se sentent peu à l’aise avec les mathématiques même s’ils reconnaissent l’importance de cette discipline pour la société. À la suite de cette consultation et des Assises des mathématiques de 2022, le CRNS a défini des orientations prioritaires, dont l’amélioration de l’inclusion. Mais comment rendre les mathématiques plus accessibles à tous ?

Les participants à la consultation de 2025 suggèrent notamment de « généraliser des méthodes d’enseignement variées, concrètes, ludiques et encourageantes, qui valorisent notamment le droit à l’erreur, tout au long de la scolarité ».

Dans ce sens, depuis plusieurs années, nous expérimentons dans des classes ordinaires (avec l’hétérogénéité des profils d’élèves qui les caractérisent !) des séquences de mathématiques inclusives. En quoi se distinguent-elles des modes d’enseignement classiques ? Et que nous apprennent leurs résultats ?

Mettre l’élève en situation de recherche

Ces séquences de maths inclusives s’appuient sur des situations à dimension adidactique, c’est-à-dire des situations qui intègrent des rétroactions de sorte que l’élève n’ait pas besoin que l’enseignant lui apporte des connaissances. C’est en interagissant avec la situation et en s’adaptant aux contraintes de celle-ci que l’élève construit de nouvelles connaissances. Il ne le fait pas en essayant de deviner les intentions didactiques de l’enseignant (c’est-à-dire en essayant de deviner ce que l’enseignant veut lui enseigner), d’où l’appellation « adidactique ».

Comme le dit le spécialiste de l’enseignement des maths Guy Brousseau, à l’origine de ce concept dans les années 1970-1980 :

« L’élève sait bien que le problème a été choisi pour lui faire acquérir une connaissance nouvelle, mais il doit savoir aussi que cette connaissance est entièrement justifiée par la logique interne de la situation et qu’il peut la construire sans faire appel à des raisons didactiques. »

Ces situations ont un potentiel identifié depuis longtemps et mis à l’épreuve dans les classes à grande échelle depuis 40 ans (surtout du premier degré, notamment dans l’école associée au Centre d’observation et de recherches sur l’enseignement). Ces travaux ont également donné lieu à des ressources pour les enseignants, par exemple la collection Ermel.

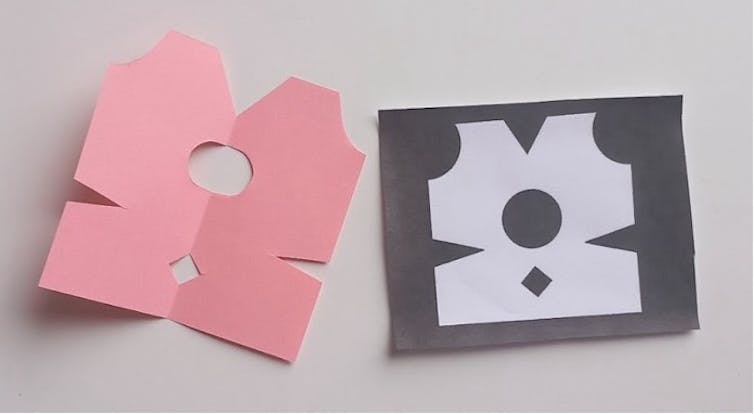

Dans le cadre de nos recherches, nous avons, par exemple, conçu et testé dans plusieurs écoles (REP+, milieu rural, milieu urbain…) une séquence en CM1-CM2 qui s’appuie sur la situation des napperons de Marie-Lise Peltier. Les élèves y ont à disposition une feuille de papier carrée, ils doivent reproduire un modèle de napperon en pliant et en découpant leur feuille. C’est la notion de symétrie axiale qui permet de découper un napperon conforme au modèle, et l’élève peut s’autovalider en comparant sa production au modèle donné.

Fourni par l’auteur

Mettre en œuvre une situation à dimension adidactique peut s’avérer complexe, car le rôle de l’enseignant diffère de ce dont il a l’habitude ; ici, il n’apporte pas directement les connaissances même s’il peut aider les élèves à résoudre la tâche.

De plus, les élèves peuvent élaborer des stratégies très diverses, ce qui peut les déstabiliser. Cependant, cette diversité constitue également une richesse du point de vue de l’inclusion, car chaque élève peut s’investir à la hauteur de ses moyens. Par ailleurs, ces situations permettent de stimuler l’engagement des élèves et les mettent dans une véritable activité de recherche, ce qui constitue le cœur des mathématiques.

Donner du sens aux notions mathématiques

À l’heure actuelle, ce type de situations est peu mis en œuvre, en particulier auprès des élèves en difficulté, car les enseignants ont plutôt tendance à penser qu’il faut découper les problèmes complexes en tâches les plus simples possibles pour s’assurer de la réussite des élèves. Cependant, la réalisation juxtaposée de tâches simples et isolées ne permet pas, souvent, de donner du sens aux notions mathématiques en jeu ni de motiver les élèves.

Dans l’exemple autour des napperons, nous avons constaté qu’en s’appuyant sur les rétroactions, mais aussi parfois sur leurs pairs et sur les conseils de l’enseignant, la majorité des élèves de CM1-CM2 que nous avons observés réussit à produire un napperon conforme au modèle, alors même que, parmi ces élèves, plusieurs avaient été signalés comme étant « en difficulté ».

Même les élèves n’étant pas arrivés à produire un napperon conforme dans le temps imparti se sont fortement engagés, comme en témoigne le nombre important de réalisations. Nous pouvons faire l’hypothèse que cette situation pourra constituer une situation de référence pour eux quand ils aborderont de nouveau la notion de symétrie axiale.

À lire aussi :

Six façons de faire aimer les maths à votre enfant

Les aspects positifs et les défis que nous avons pu identifier dans notre recherche corroborent les résultats obtenus par d’autres chercheurs et chercheuses qui ont étudié la mise en œuvre de situations à dimension adidactique pour travailler diverses notions mathématiques, à différents niveaux scolaires, auprès de publics variés, notamment auprès d’élèves présentant une déficience intellectuelle ou un trouble dys, en France et au Québec.

Ainsi, même si ce concept n’est pas nouveau, l’appui sur les situations à dimension adidactique nous semble toujours une piste intéressante et actuelle pour penser l’enseignement des mathématiques pour tous. Cependant, il est nécessaire de donner aux enseignants les moyens de les mettre en œuvre de manière satisfaisante, par exemple en allégeant le nombre d’élèves par classe et en les accompagnant en formation initiale et continue.

![]()

Florence Peteers est porteuse de la Chaire Junior SHS RIEMa financée par la région Île-de-France et a reçu des financements du PIA3 100% IDT (inclusion, un défi, un territoire) porté par l’Université de Picardie Jules Verne.

Elann Lesnes a reçu reçu des financements du PIA3 100% IDT (inclusion, un défi, un territoire) porté par l’Université de Picardie Jules Verne.

– ref. Apprendre les maths autrement : les pistes de la recherche – https://theconversation.com/apprendre-les-maths-autrement-les-pistes-de-la-recherche-272586