Source: The Conversation – (in Spanish) – By Ana María Iglesias Botrán, Profesora del Departamento de Filología Francesa en la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. Doctora especialista en estudios culturales franceses y Análisis del Discurso, Universidad de Valladolid

Durante décadas en el olvido, Paul Poiret (París, 1879-1944) fue el diseñador de alta costura más importante de los inicios del siglo XX, el primero que realmente cambió la silueta femenina.

United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division

Con su personalidad arrolladora creó un proyecto creativo integral, una empresa próspera que abarcó todas las artes decorativas, y fue pionero en un estilo de negocio que inspiró a muchos diseñadores posteriores.

Además de ropa, fabricó perfumes, publicó libros, decoró barcos, viajó por el mundo, creó una escuela de arte para niñas, se empapó de las vanguardias y fue siempre consciente de estar generando un universo nuevo. Su desbordante creatividad lo llevó finalmente a la ruina y al olvido, pero siempre estuvo orgulloso de su aportación.

Afortunadamente, el Museo de Artes Decorativas en París le dedica en estos meses una exposición cuyo nombre le define: La moda es una fiesta.

Nueva silueta femenina

Liberar el cuerpo de la mujer fue su primer objetivo. Paul Poiret observaba y respetaba la anatomía natural femenina, y lograba que la ropa acompañase el movimiento del cuerpo con ligereza. Creó en sus diseños líneas rectas o curvadas y drapeados estratégicos que conservaban la elegancia y el estilo único de su firma.

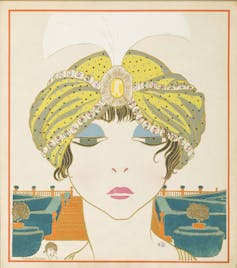

En 1906 descartó definitivamente el corsé y diseñó sus creaciones partiendo del sujetador, un acto pionero de modernidad vigente hasta hoy. Diseñó la falda-pantalón, caftanes, kimonos y turbantes y también innovó al ser el primero en presentar a sus modelos con el pelo corto.

Este estilo novedoso y adelantado por su comodidad se puso de moda y causó furor entre las mujeres de la alta sociedad, las cocottes y las artistas más relevantes.

Musée des Arts Décoratifs

Investigación y desarrollo

Pretendía crear una nueva estética, un lenguaje visual insólito. Por eso contrató a un químico para fabricar en su propio laboratorio nuevos tintes, investigando combinaciones armoniosas e innovadoras.

Para el diseño de los estampados, fundó en 1911 el Atelier Martine, un lugar de formación gratuita para jóvenes con talento artístico y pocos recursos. Allí, las niñas dibujaban libremente inspiradas en la naturaleza, sin intervención externa ni normas académicas.

Poiret transformaba estos dibujos de flores, alcachofas y margaritas en elementos decorativos que aplicaba tanto a tejidos de ropa como a cortinas, cojines y alfombras y otros objetos del hogar.

Primer modisto con perfume

Para él la moda no se limitaba a la ropa, sino a un estilo de vida basado en el arte que debía romper con los gustos de la belle époque e impregnarlo todo. Por eso, fue el primer diseñador en crear una línea de perfumes, ya que consideraba que el aroma también era una muestra del estilo personal.

Diez años antes de que Chanel sacara su mítico “N.º 5” (1921), Paul Poiret ya había fundado la sociedad comercial Les Parfums de Rosine (según el nombre de su hija mayor). Durante una década, fue el único modisto-perfumista de París, hasta que, además de Chanel, la casa Whorth (en 1924) y el diseñador Jean Patou (en 1925) siguieron sus pasos.

Para la creación de dos de sus aromas se inspiró en sus hijas. Otros evocaban el imaginario francés, como “Arlequinade”, el exotismo, como “Aladdin” o “Nuit de Chine” (Noche china), o la sensualidad, como “Fruit défendu”. Eran perfumes intensos, con ingredientes florales y exóticos.

Una vez más, recurrió a artistas para su producción. Todos los frascos eran sorprendentes, novedosos y elegantes, con formas geométricas o florales y tapones ornamentales. Son en sí mismos objetos de lujo y obras maestras pioneras del arte decorativo. Para el perfume “Arlequinade (1923)”, por ejemplo, cuya fragancia había sido creada por el perfumista Henri Alméras, contó con la artista del cubismo Marie Vassilieff para diseñar el frasco y con el escultor en vidrio Julien Viard para fabricarlo.

Hoy en día los perfumes de Poiret se conservan en la Osmothèque de París.

La moda es una fiesta

En su autobiografía Vistiendo la época cuenta que disfrutaba de la vida en todo momento. Por eso compartía su creatividad organizando fiestas temáticas que se volvieron míticas.

La primera, celebrada el 24 de junio de 1911, se tituló “La Mille et deuxième Nuit” (“La mil y dos noches”), y estaba inspirada en el clásico libro de relatos Las mil y una noches. En la invitación se indicaba claramente que “un disfraz inspirado en cuentos orientales [era] absolutamente obligatorio”.

Les Arts Décoratifs

Poiret se disfrazó de sultán y su esposa Denise de princesa enjaulada, con pantalones de estilo oriental y una túnica con faldas acopladas que sería recordada por todos. La decoración, la comida, la música y las actuaciones giraron en torno al tema central y más de 300 invitados –artistas, escritores, aristócratas– asistieron luciendo diseños del anfitrión.

Fue una fastuosa puesta en escena de sus creaciones: exótica, innovadora, sorprendente, teatral y delirante, como las que hoy son habituales en las presentaciones de las grandes casas de moda.

¿Catálogos de moda u obras de arte?

Quiso que sus diseños llegaran a todos los rincones de Europa. Creó catálogos promocionales con ilustraciones de artistas de la época que él eligió y contribuyó a consagrar.

El 1908 le encargó uno a Paul Iribe: Los vestidos de Paul Poiret. En 1911 hizo lo mismo con Georges Lepape en Las cosas de Paul Poiret. En ellos, las mujeres llevan puestos sus diseños y aparecen fumando, en fiestas, charlando, rodeadas de escenarios que evocan lujo y sofisticación.

Estas recopilaciones son consideradas obras de arte de gran valor y hoy se conservan en la Biblioteca Nacional de Francia, el Museo Metropolitano de Arte de Nueva York y el Victoria & Albert Museum de Londres.

Fuente inagotable de inspiración

United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division

Su estilo influyó en grandes de la moda que le sucedieron: Christian Dior, Jean Paul Gaultier y John Galliano, entre otros, así como en Gabrielle Chanel. La diseñadora Elsa Schiaparelli, gran amiga y admiradora, le consideraba el Leonardo Da Vinci del sector.

Fue el precursor de los vestidos de los años 20 que Chanel retomó e hizo evolucionar con la creación de una elegancia funcional. Si Poiret renovó y liberó la silueta, Chanel la hizo cómoda, acortando las faldas, dejando libre la cintura, con materiales ligeros y adaptados al movimiento natural del cuerpo. Paul Poiret deploraba el estilo básico y extremadamente sencillo de Chanel que, curiosamente, él mismo había contribuido a crear y que denominaba el misérabilisme de luxe.

El camino a la ruina y el olvido

Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, Poiret no desistió en su estilo artístico y fastuoso, sin tener en cuenta la realidad social: ante la escasez de la contienda, ignoró por ejemplo tejidos austeros como la lana.

Tampoco atendió a los nuevos gustos de la alta sociedad de posguerra: bailar el tango, bañarse en el mar, conducir coches, el deporte… Una vida más veloz y dinámica exigía vestidos cómodos y adecuados para cada ocasión. Otros diseñadores más conscientes de los cambios, como Chanel, supieron aprovechar los acontecimientos y triunfar.

Sus gastos desmedidos, su resistencia al cambio y las malas decisiones empresariales lo llevaron a la bancarrota. En 1929 tuvo que cerrar su casa de moda, todos sus bienes fueron subastados y su aportación ignorada.

Fue así como el diseñador que anunció la moda moderna y cuya influencia llega hasta hoy murió en 1944: enfermo, arruinado y olvidado.

![]()

Ana María Iglesias Botrán no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

– ref. El visionario de la alta costura moderna: el olvidado Paul Poiret – https://theconversation.com/el-visionario-de-la-alta-costura-moderna-el-olvidado-paul-poiret-266733