Source: The Conversation – UK – By Parveen Akhtar, Senior Lecturer: Politics, History and International Relations, Aston University

A core function of political parties is to nurture talent and, in some cases, provide a credible path to power for ambitious politicians. In this fraught climate, Reform UK increasingly appears to be an alternative route for those who see no such path via the Conservative party.

Before Robert Jenrick’s sacking (over his own supposed plan to defect), Nadhim Zahawi was the latest, and arguably the most high-profile, Conservative to throw his lot in with Reform. It seems a growing number of former Conservative MPs and councillors see Reform as a second chance at political relevance.

A former chancellor of the exchequer, albeit for just two months at the tail end of Boris Johnson’s premiership, Zahawi brings with him the symbolic capital of high office.

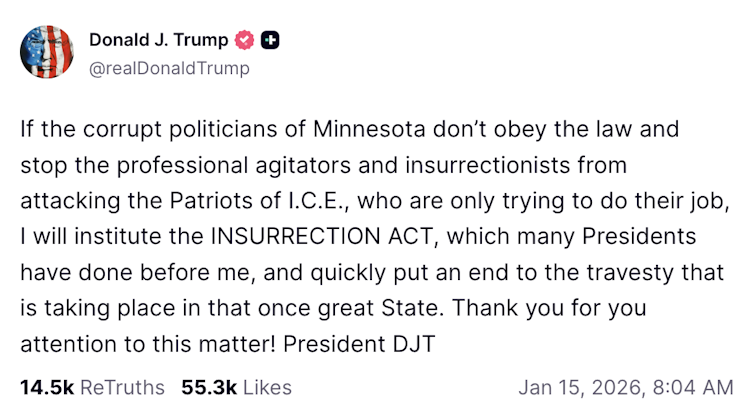

In announcing his switch, Zahawi claimed that only a “glorious revolution” could fix a “broken” Britain: “Nothing works, there is no growth, there is crime on our streets, and there is an avalanche of illegal migration that anywhere else in the world would be a national emergency.” The rhetoric is familiar, but the messenger matters.

Zahawi’s defection comes at a delicate moment for Nigel Farage. As Farage faces renewed scrutiny over allegations of racism and antisemitism during his school days, the recruitment of high-profile, non-white former Conservatives is both politically convenient and strategically risky.

Although Reform has undergone a rapid programme of “professionalisation” under its chairman, Zia Yusuf, these defections remain significant. Reform can now more plausibly claim to house people who have sat around the Cabinet table and understand how government works. Zahawi brings name recognition and governing experience to a party still widely caricatured as a vehicle for political amateurs. This matters for a party attempting to shift from a protest movement to an electoral contender.

Reform’s anti-Muslim reputation

But Zahawi represents more than experience. Alongside Reform’s London mayoral candidate, Laila Cunningham, his presence helps Farage rebut accusations that Reform is an anti-Muslim or racist party. Cunningham, formerly a Conservative councillor in London, defected to Reform in June 2025. She cited frustration with both main political parties and their failure on crime and immigration.

At a time when diversity within Reform has become a flashpoint for internal dissent, this is no accident.

For Farage, this is a familiar manoeuvre. His relationship with Islam has always been more complicated than that of Europe’s explicitly ethnonationalist right. He left Ukip in 2018 after then party leader Gerard Batten appointed far-right activist Tommy Robinson as an adviser to the party. Farage criticised Batten’s fixation with Islam, and said Ukip was drifting into a singularly anti-Muslim posture.

He has repeatedly distanced himself from Robinson, and his clashes with figures such as former Reform MP Rupert Lowe reflect an ongoing effort to differentiate Reform from the far right. The aim is clear: to position Reform as uncompromising on immigration without being reducible to crude racial politics.

The presence of non-white, Muslim politicians may therefore make Reform appear a viable option for voters who want “change”, but are reluctant to back a party they perceive as overtly racist or anti-Muslim.

Yet this same strategy risks alienating other Reform supporters. Farage knows that his digital base is often significantly further to the right.

Farage currently faces claims from a number of former classmates who describe a pattern of racist bullying during his schooldays. Farage has denied the claims – while acknowledging he engaged in “aggressive banter”, he said that he “never directly racially abused anybody”.*

For someone who has built a career on denying personal racism while mobilising grievance politics, this is uncomfortable territory. Zahawi’s defection, like others before it, functions as reputational insulation: evidence that Reform is inclusive, pragmatic and electorally serious.

Meanwhile, Farage is receiving increasing financial backing from wealthy donors, which provides a sense of security and room to manoeuvre, even if parts of his grassroots support online revolts. In some ways, Farage is skating on thin ice. But he knows his backers have significant resources. He is willing to compromise on his most vociferous base in the immediate term if the bigger vision still holds true.

In this sense, Zahawi’s move exposes a central contradiction about Reform. Is it a refuge for failed politicians rejected by the Conservatives? Or is it a party making a serious attempt to broaden its electoral coalition? The answer may be both.

What is clear is that Farage is attempting to play two games at once: reassuring sceptical voters that Reform is not racist, while continuing to benefit from a base that thrives on racialised outrage.

![]()

Parveen Akhtar has previously received funding from the ESRC and the British Academy

Tahir Abbas has received research funding from the European Commission via the H2020 Framework Programme for the DRIVE project, and via the Internal Security Fund Police stream for the PROTONE project.

– ref. Reform UK: will high-profile defections change the party’s image? – https://theconversation.com/reform-uk-will-high-profile-defections-change-the-partys-image-273533