Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Lightning Jay, Assistant Professor of Teaching, Learning and Educational Leadership, Binghamton University, State University of New York

Many of our college freshman students will have seen and read about the Jan. 3, 2026, U.S. military operation in Venezuela that culminated in the arrest of its leader, Nicolás Maduro, and his wife, Cilia Flores. The U.S. has charged Maduro and Flores with conspiracy and drug trafficking. Maduro and Flores are imprisoned in New York City, awaiting trial.

Some freshmen this semester will likely say Maduro’s unusual arrest violates international law. Others may view it as a decisive step in the U.S.’s fight against narco-terrorism.

That’s in part because the U.S has no national curriculum, and high school history courses often rely on teachers’ discretion, even more so than in other content areas. This results in history being taught a lot of different ways across schools.

As scholars of Latin American history and history education in the U.S., we know that most American high school students learn about the ancient civilizations in Latin America and a few other key flash points in history.

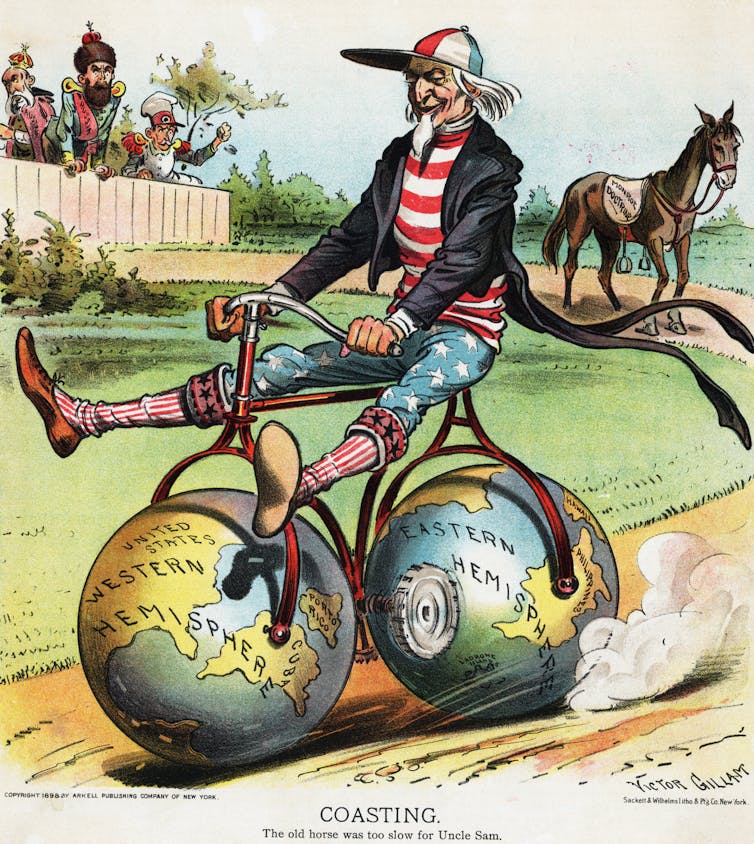

But few, we suspect, will understand Maduro’s arrest as part of a long history of the U.S.’s interventions in Latin America, stretching back to the Monroe Doctrine in the 1800s. President James Monroe introduced this foreign policy in an 1823 speech, saying that the U.S. would not allow European colonization or interference in the Western Hemisphere.

XNY/Star Max/Contributor via Getty Images

A partial, skewed history

In high school world history courses, teachers in the U.S. often rely on case studies and examples to indicate historical trends.

High school students are likely to learn about the Inca, Maya and Aztec civilizations as representatives of pre-Columbian Latin America. They read about Spanish conquistadors such as Hernán Cortés, who overthrew the Aztec empire, and Francisco Pizarro, who conquered the Incas in the early 1500s.

They will learn about how most Latin American countries, including Mexico, Argentina, Colombia and Guatemala, gained independence in the early 1800s.

Often, students learn about these countries’ fights for independence, with the case example of the Haitian Revolution. They may learn about Simón Bolívar, the grand Venezuelan military officer and liberator who played a decisive role in the independence movements of countries including Venezuela, Colombia and Bolivia.

Students also often learn about more recent eras, including the Cuban missile crisis, a dangerous tipping point between the U.S. and the Soviet Union that brought the world close to nuclear war in 1962.

But overall, in U.S. history courses the U.S. is typically the main character and Latin America is treated as a place where the U.S. exerts power.

An example of this narrative includes the U.S.’s failed attempt to overthrow the Cuban government in 1961, during the Bay of Pigs invasion.

What US high school students miss

It is no surprise that students who learned this version of Latin American history in high school would have many questions about Maduro’s recent arrest – including who the longtime leader is.

A fuller exposure to Latin American history would include, among other things, lessons about neoliberal capitalism, which has long shaped the politics, economies and societies of Latin America. This is a U.S.-government supported policy that promotes less internal government intervention and more free-market capitalism.

Even though most Latin American countries achieved independence just 30 to 40 years after the U.S., not all presidential administrations in the U.S. fully accepted these nations’ freedom.

In 1904, Theodore Roosevelt added an additional text called a corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, stating that the U.S. could intervene in the internal affairs of any Latin American country in cases of wrongdoing.

By the late 1800s, the U.S. had conquered more than half of Mexico’s territory and annexed Puerto Rico. It also began occupying Cuba in 1898, after Spain lost the Spanish-American War and control over the island.

The U.S. militarily and politically then backed a 1903 revolution that gave Panama independence from Colombia. Panama’s independence led to a treaty that let the U.S. build and control the Panama Canal for nearly a century.

Bettmann/Contributor via Getty Images

A strong influence

Overall, the U.S. intervened in Latin America more than 40 times from 1898 to the mid-1990s.

Some of these interventions involved coups against democratically elected officials – including Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán in Guatemala in 1954 and Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973. These coups often led to civil wars or enduring military regimes that the U.S. claimed were necessary to fight the spread of communism.

Chile was then among the countries – including Argentina and Uruguay – that implemented economic policies in the 1970s that kept markets open to foreign businesses and governments, fostering dependence on wealthier nations.

Some Latin American countries, including Mexico and Brazil, struggled financially in the 1990s.

The U.S. and international financial institutions gave conditional loans that promoted austerity – meaning raising taxes and cutting public spending – and market liberalization, which reduces governmental restrictions over an economy. These loans stabilized some economies in the short term, but also made other problems, such as inequality and debt, worse.

In the early 2000s, several countries, including Brazil, Ecuador and Bolivia, elected left-leaning leaders who advocated for alternatives to this U.S.-backed economic policy. Ultimately, though, their reforms were often limited and not politically stable.

A more complete history

During a Jan. 4, 2026, press conference, President Donald Trump used a new term, the “Donroe Doctrine,” to describe his administration’s plans to claim dominance in the Western Hemisphere.

One day later, Vice President JD Vance doubled down: “This is in our neighborhood,” he said in an interview about Maduro’s capture. “In our neighborhood, the United States calls the shots. That’s the way it has always been. That’s the way it is again under the president’s leadership.”

Learning a more complete version of Latin American history in high school won’t prevent our college students from bringing questions to class about the U.S.’s capture of Maduro, and why Trump has said the U.S. will “run” Venezuela.

But this knowledge might help our students ask more complex, nuanced questions, such as whom national security strategies actually benefit the most.

Understanding Latin America is not merely a requirement for interpreting headlines about Venezuela but a prerequisite for Americans to understand themselves and their place in the world.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. A more complete Latin American history, including centuries of US influence, helps students understand the complexities surrounding Nicolás Maduro’s arrest – https://theconversation.com/a-more-complete-latin-american-history-including-centuries-of-us-influence-helps-students-understand-the-complexities-surrounding-nicolas-maduros-arrest-272984