Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Jimmy Aguilar, PhD Candidate in Urban Education Policy, University of Southern California

President Donald Trump on April 23, 2025, signed an executive order that aims to change the higher education accreditation process. It asks accrediting agencies to root out “discriminatory ideology” and roll back diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives on college campuses.

The Conversation asked Jimmy Aguilar, who studies higher education at the University of Southern California, to explain what accreditation is, why it matters and how the Trump order seeks to change it.

What is accreditation and how does it work?

Accreditation is a process that evaluates whether colleges and universities meet standards of academic rigor, institutional integrity and financial stability.

In the United States, there were 88 accrediting agencies during the 2022-23 school academic year.

The agencies are formally recognized by the Department of Education and the Council for Higher Education Accreditation.

Accreditation is not a one-time stamp of approval, but a continuous process.

At its core, accreditation is a guarantor of quality in higher education.

The process involves self-assessment and peer review visits.

Colleges typically undergo a full review every five to 10 years, depending on the accrediting agency.

Institutions must meet standards for curriculum, faculty, student services and outcomes, and provide documentation.

Then, federally recognized accrediting agencies review the documentation.

Teams, often comprised of peer reviewers from other colleges, conduct campus visits and evaluations before granting or reviewing accreditation.

Why do universities need to be accredited?

Accreditation assures students, employers and the public that an institution meets basic academic standards.

It also signals credibility and secures federal financial support.

Without it, colleges cannot access key funding sources such as Pell Grants and federal student loans.

The funding is essential for college budgets and students’ access to higher education.

Accreditation is also required for professional licensure in fields such as teaching, nursing, medicine and law.

It also helps ensure that students can transfer credits between institutions.

What does Trump’s executive order do?

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

The executive order would reshape the college accreditation system, aligning it with the administration’s political priorities. Those priorities include the rollback of DEI initiatives.

The order seeks to use federal oversight to weaken institutional DEI policies and priorities. It also promotes new standards aligned with the administration’s interpretation of “merit-based” education.

The executive order also directs the Department of Education to penalize agencies that require colleges to implement DEI-related standards.

The Trump administration claims that such standards amount to “unlawful discrimination.”

Penalties may include increased oversight or loss of federal recognition. This would render the accreditation seal meaningless, according to the executive order.

The order also proposes a broad overhaul of the accreditation process, including:

-

Promoting “intellectual diversity” in faculty hiring. The executive order argues that promoting a broader range of viewpoints among faculty will enhance academic freedom. Critics often interpret this language as an effort to increase conservative ideological representation.

-

Streamlining the process for institutions to switch accreditors. During Trump’s first term, his administration removed geographic restrictions, giving colleges more flexibility to choose. The new executive order goes further. It makes it easier for schools to leave agencies whose standards they disagree with.

-

Expanding recognition of new accrediting agencies to increase competition.

-

Linking accreditation more directly to student outcomes. This would shift focus to metrics such as graduation rates and earnings, rather than commitments to diversity or equity.

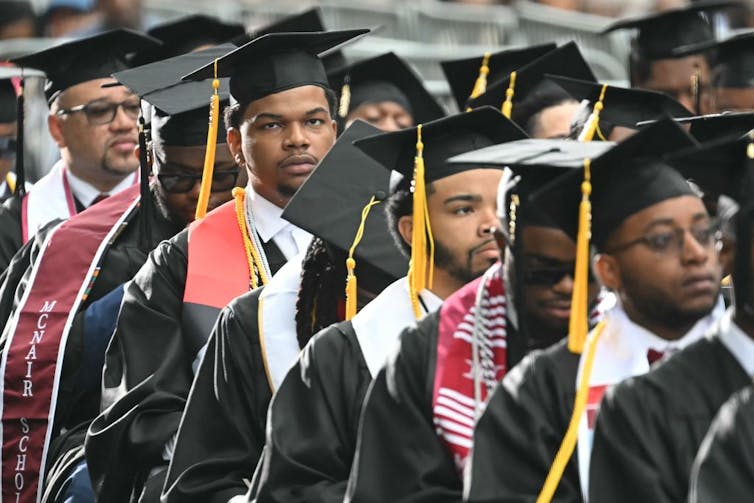

Joe Daniel Price/Getty Images

The executive order singles out accreditors for law schools, such as the American Bar Association, and for medical schools, such as the Liaison Committee on Medical Education.

The order accuses them of enforcing DEI standards that conflict with a 2023 Supreme Court ruling that outlawed affirmative action in university admissions.

However, the ruling was limited to race-conscious admissions. It did not directly address faculty hiring or accreditation standards.

That raises questions about whether the order’s interpretation extends beyond the scope of the court’s decision.

The ruling has nonetheless been a point of contention in the debate over diversity, equity and inclusion.

The American Association of University Professors and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law have denounced the executive order.

The groups argue that it threatens to politicize accreditation and suppress efforts to promote equity and inclusion.

Nevertheless, the order represents a push by the federal government to influence higher education governance.

![]()

Jimmy Aguilar does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. How proposed changes to higher education accreditation could impact campus diversity efforts – https://theconversation.com/how-proposed-changes-to-higher-education-accreditation-could-impact-campus-diversity-efforts-255309